A doksi online olvasásához kérlek jelentkezz be!

A doksi online olvasásához kérlek jelentkezz be!

Nincs még értékelés. Legyél Te az első!

Tartalmi kivonat

Source: http://www.doksinet Federal dynamics and European Union crisis politics Philipp Trein University of Lausanne July 27, 2017 – First draft – Abstract This paper analyzes the politics amongst the member states of the European Union (EU) in times of crisis through the lens of comparative research on federal dynamics. The paper assumes that, despite its differences from federal states, the EU faces similar policy challenges in times of crisis. I argue that the EU resembles federal states regarding the degree to which economic and monetary policy competences have been transferred to the central level but that the EU does not posses the capacity to respond to policy challenges by temporarily pooling discretion at the center as federal states do. During the current crises, the EU faces opportunistic behavior of member states, similar to other federal systems. Nevertheless, other than federal countries, the EU, lacks institutional mechanisms to fend off opportunistic interests of

member states and the policy capacity to respond to asymmetric shocks effectively. Therefore, it faces challenges of desolidarization, i.e, fierce Euro-skepticism, and a systemic federal crisis Overall, this paper contributes to the understanding of EU politics by applying the findings from the literature on federal dynamics to the European Union. This paper analyzes the politics amongst the member states of the European Union (EU) in times of crisis through the lens of the research on federal dynamics. The paper argues that, despite its obvious differences from federal states, the EU has faced similar policy challenges during crisis. Nevertheless, the EU cannot respond to urgent policy challenges as effectively as federal states because it is unable to temporarily centralize sovereignty at the top of the (monetary) union in times of crisis, as it is the case in federal states. As a consequence, the interests of some of the member states de facto dominate the decisions about common

crisis policies at the European level. Thus, the EU cannot respond to urgent policy challenges effectively – in the sense of policy effectiveness and 1 Source: http://www.doksinet democratic effectiveness –, which results in a systemic destabilization of union due to desolidarisation amongst the member states. In other words, the price of flexible and differentiated integration and monetary solidarity is that the EU lacks an effective governance mode to respond to crises policy challenges without risking desolidarization and a systemic crisis of the EU. Federalism has been a core topic to the analysis of European integration. Although European integration has taken above all a path of economic and differentiated political integration (Leuffen, Rittberger & Schimmelfennig 2012, Schimmelfennig, Leuffen & Rittberger 2015), many researchers have analyzed the EU under the aspects of federalism.1 In this literature, there is consensus that the EU is different from federal

states because important elements of state sovereignty, such as the control over the military, taxation, and redistribution remain locked in almost entirely at the level of the member states (Burgess 2000, Trechsel 2005, Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017). To account for difference between European integration and federalization, scholars have referred to multilevel governance (Hooghe & Marks 2003), regulatory federalism (Kelemen 2009), or integration by stealth (Majone 2009) just to name a few concepts that figure prominently in the debate. Against the backdrop of the economic and ensuing political crisis of the EU, researchers have made a number of new contributions that study the EU under the promises of federalism. This research outlines the problem of constitutional legitimacy in the European federation (Niesen 2017), the potential of a fiscal union (Costa Cabral 2016), democratic representation (Benz 2017, 515), parliamentary activism in the EU compared to federal states

(Bolleyer 2017, 535-536) as well as the political dynamics between the member states and the EU (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017). This paper contributes to this literature by undertaking an analysis that analyzes the federal dynamics in the European Union. In harkening back to the literature on federal dynamics in general (Bednar 2009, Benz & Broschek 2013b) and to the works on dynamics of federal states especially (Braun & Trein 2013b, Braun & Trein 2014, Trein & Braun 2016), this article analyzes how EU institutions shape member states’ policy preferences in dealing with asymmetric crisis events that require an immediate policy response for the entire union. The paper assumes that due to the economic, monetary and (partial) political integration, the EU faces policy challenges that are similar to the ones in federal states. In federal countries, even in the most decentralized federations, such as Canada, Switzerland or the U.S, the central government responds to

crisis events, even if 1 For a detailed literature overview read also: (Fossum & Jachtenfuchs 2017). 2 Source: http://www.doksinet these policy responses require a temporary centralization of competencies. In other words, anticrisis policies come along with a temporarily limited pooling of the otherwise shared sovereignty at the central level, in order to deal with the crisis problem, such as an economic crisis, even if pooling of sovereignty interferes with the opportunistic interests of the member states. Temporary centralization helps to avoid that the desolidarization tendencies in the federation, which might come along with crisis events, turn into systemic crises that call into question federal integration entirely. I argue that differentiated political integration, which distinguishes the EU and from federal states, does not allow for effective temporary centralization of powers in order to deal with crisis pressures. In fact, if fast and efficient policy responses are

needed, decision making at the EU level will be concentrated amongst the member states governments and the European Commission. These actors lack a) democratic legitimacy and power as in the case of the European Commission or b) are guided by the opportunistic interests of the majority of the member states rather than by dealing with the policy problem from the perspective of the union as a whole. Two examples illustrate this argument: firstly, intergovernmental competition and eventually the interests of the creditor countries dominated de facto the bailout packages for Greece and other crisis countries without taking into consideration the social consequences of these policies. Secondly, in the refugee crisis, an effective redistribution of the refugees amongst member states failed again due to the intergovernmental conflicts. In short – other than in federal states – the EU lacks an institutional mechanism to cope effectively with member state opportunism. As a consequence,

desolidarization increased amongst members of the EU and the Eurozone, and voters increased their support for EUcritical parties. The yes-vote for Brexit can be interpreted as another symptom of this mechanism This paper teaches us that differentiated integration in the EU does not allow for effective temporary centralization. In the EU, despite the economic and political integration, sovereignty is inflexible and cannot be pooled at the central level in order to deal with pressing policy challenges such as economic crises. Thus, unless the EU finds a way to respond to crisis problems in a way that is effective with regard to problem-solving and democratic legitimacy, any new crises is likely to result in desolidarization and a systemic crises of the EU. To remedy this problem, the paper suggests that reforms of the EU should strengthen solidarity amongst the members of the union. 3 Source: http://www.doksinet Federal dynamics in times of crisis The theoretical approach this paper

uses to analyze federal dynamics in EU politics during times of crisis is based on the research on federal dynamics. In this literature, researchers have focused on the variation between federal states, the dynamics within federal systems (Benz & Broschek 2013a, 367-372), and on the institutional conditions under which federations remain stable or even break up (Bednar 2009, 95-127). In the research on the EU and federalism, authors have referred to the mentioned literature but without an explicit focus on instability and stability of the EU in the light of the Union’s federal dynamics (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017). Nevertheless, the research on anticrisis policies and politics in federal states provides important insights for understanding politics of crisis in the EU and its consequences of federal stability. Therefore, this article starts from the literature on institutional and policy-related dynamics in federal states during the economic, financial, and debt crisis (Braun

& Trein 2013a, Braun & Trein 2013b, Braun & Trein 2014, Braun, Ruiz-Palmero & Schnabel 2017). This literature has analyzed how federal states responded to the policy challenges that emerged as a consequence of the financial and economic as well as the ensuing debt crisis after 2007. The research has demonstrated that – once the economy went down and debt rates augmented – the federal government took action in order to deal with these crisis induced policy challenges. Against the crisis background, national governments responded with economic stimulus programs that entailed for example financial transfers to subnational governments (Braun & Trein 2013b, 351) as well as measures to bail out subnational governments and to enforce budgetary discipline in the future (Braun & Trein 2013a, 144-151). Subnational governments for their part pursued their own policies, which corresponded sometimes with the measures of the national government’s measures, but there is

also evidence for opportunism (Braun & Trein 2013b, 351)(Braun & Trein 2014, 811), i.e, some subnational governments pursued policies at odds with the federal governments’ measures or refused to implement central government’s policies because they considered them to be against their interests Furthermore, there are instances of desolidarization, which means that some of the member states in federations questioned solidarity with other members of the federation, for example by requesting reforms of the fiscal equalization system or by considering to leave the federal state (Braun & Trein 2014, 811). In all federations, the interventions of the central government where temporary and did not 4 Source: http://www.doksinet results in debates of principle about the federal order. Belgium, Canada, and Spain are somewhat exceptional to this because in these countries the crisis came along with debates about the legitimacy of the federal order and the anti-crisis policies

coincided with federal conflicts (Braun & Trein 2014, 811). For example, in Canada, there were debates about the consequences of the demand crisis for fiscal equalization (Dubuc 2009) and in Spain, the crisis fueled the conflict between Catalonia and the centre (Colino & Hombrado 2015). Nevertheless, overall, federal states managed the crisis well – in the sense that there is no instance of a federation breaking up. Temporary interventions by central governments, the common control of over-borrowing, and the presence of stabilizing institutions to cope with constituent units’ opportunism, i.e, safeguards (Braun, Ruiz-Palmero & Schnabel 2017) helped federal countries to retain institutional stability, during the crisis period. This literature on federal dynamics in European crisis provides us with the following insights that are important for analyzing the politics of the European Union and its member states during times of crisis. 1. In political systems where two or

more levels of government share sovereignty, external crisis events results in opportunistic behavior of the member states of the federation that seek to defend their interests against other member states and the federal government. 2. In federal states, there was a compromise that the members of the federation and the federal government should resolve the crisis together As a consequence, central government put forward the first policy responses to the crisis, which entailed a temporal centralization of discretion to the federal level. In other words, anti-crisis policies contained a pooling of sovereignty at the central level in order to meet the demand for problem solving. Member states did not challenge the temporary shift of discretion to the centre to deal with the crisis. On the other hand, anti-crisis policies did not result in permanent authority migration (Gerber & Kollman 2004) to the central level. 3. Member states of federal countries did not generally challenge the

temporary shift of policy discretion to the centre during the crisis. Overall, conflicts between the member states of the federation and the central government about crisis policies did not spill-over into federal conflicts about the balance of power in the federation in general (Braun, Ruiz-Palmero & Schnabel 2017, 34). Furthermore, the temporary centralization assured fast problem solv5 Source: http://www.doksinet ing and avoided that opportunistic interests of member states captured federal politics and that desolidarizing tendencies between member states turned into systemic conflicts in the federation. The EU and federal states: differences and similarities The EU is similar to and different from federal states. According to Jenna Bednar, there are three dimensions of federalization that are relevant to federal states’ regarding the allocation of competencies between the central level and the member states: the provision of military security, economic growth, and

effective representation. Federal states try to achieve these goals by centralizing powers at the national level, decentralizing competencies to the subnational level or by sharing powers between levels of government (Bednar 2009, 25-52). In keeping in mind these three main goals of government – military security, economic growth, and effective representation – allows us to assess how the EU resembles to and differs from federal states. Differences between the EU and federal states In comparison to other federal states, the EU is a very decentralized political system. This is visible in the socioeconomic differences between the EU and federations. For example, the diversity in median household income and inequality is much higher than in the most decentralized federations, such as the U.S (Vandenbroucke 2017) In terms of the centralization of political powers, the EU differs from other federal states as it has no own major taxation power, such as an income tax, and military

affairs remain almost entirely in the hands of the member states (Costa Cabral 2016, 1285)(Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017, 600). As a consequence direct redistribution in the EU needs to be horizontal, which is something that is already immensely complicated in federal states where the federal government possesses a considerable amount of proper resources and horizontal fiscal equalization is often mixed with vertical transfers, for example in Switzerland (Braun 2009). Therefore, any horizontal redistribution should be an immensely complicated undertaking in the EU. Other than in federal states, the “EU’s material constitution is also highly malleable” (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017, 601), which is something that did not occur unintended and makes the EU different from federal states. One reason for this situation is that the EU constitution has remained highly 6 Source: http://www.doksinet contested, as the failure of the Constitutional Treaty of 2005 shows (Jachtenfuchs

& Kasack 2017, 601). The Europeanization literature has coined the term differentiated integration (Schimmelfennig & Winzen 2014, Hvidsten & Hovi 2015) to account for the particular constitutional situation of the EU. Rather than fixing a broad constitutional contract, member states continued to voice their preferences over the dilemma between common problem solving, i.e, centralization of competencies, and to retain autonomy in a differentiated manner. In other words, member states decide about their preferences for transferring power to the EU or not regarding specific policy issues, such as the Single Resolution Fund or European Stability Mechanism (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017, 601). Thus European integration follows a path of differentiated political integration (Schimmelfennig, Leuffen & Rittberger 2015, 774-779). Put differently, there is an integration of specific policies, such as regarding the common market, but little broad constitutional integration as in

federal states. Eventually, the EU differs from federal states concerning political representation. The EU has no party system that is highly centralized as most federal states do (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017, 600). In addition, the link between citizens and the representatives at the European level is rather weak and indirect. Compared to first parliamentary chambers in other federal states, the competencies of the European parliament are weak (Hueglin & Fenna 2015), and so is its input legitimacy for unified European policy solutions. Although the community method emphasizes the power of European institutions to solve common problems, intergovernmental coordination of member states remains the most important mode of decision making (Scharpf 1999, Majone 2009). Other than in federal states, EU member states have a very strong control of political decisions at the federal level. In other words, there is no institution to counterbalance the strong influence of the member

states’ governments in decision-making at the federal (EU) level (Hueglin & Fenna 2015). In times of crisis, the institutional setting at the EU level – theoretically – opens the door to transferring opportunistic interests of some member states into policies at the expenses of other members states in the shadow of consensual decision making in the European Council. This is particularly the case when fast problem solving is required, such as in the case of the economic and financial crisis or the migration crisis. Even in standard federal states, in which sovereignty can be pooled at the national level, coordination of anti-crisis policies is already quite complicated (Boin & Bynander 2015). Thus, we can expect that is even more difficult at the European level 7 Source: http://www.doksinet Similarities between the EU and federal states Despite the differences between the EU and federal states, there are some similarities between the EU and federations. Against the

background that the EU is a “regulatory state” (Majone 1994), researchers have argued that EU federalism is above all regulatory federalism (Kelemen 2009, 1-2), in which the federal state provides above all rules as regulatory unification but direct redistribution of tax money between member states of the federation does not play an important role as tax harmonization (Wasserfallen 2014) and transfer to taxation competencies to the European level remain narrow. Therefore, the EU is similar to federal states regarding its regulatory unification During the process of regulatory federalization (Leuffen, Rittberger & Schimmelfennig 2012), national states transferred competencies to the central, i.e, the European, level of government, which were mostly in the field of regulation of common market processes (Schimmelfennig, Leuffen & Rittberger 2015, 768)(Börzel 2005, 221). Against the background the three dimensions of federalism laid out by Jenna Bednar (Bednar 2009, 25-52),

the EU underwent a process of federalization – understood in the in the sense of transferring sovereignty to a central level – in the economic arena. Put differently: federalization aimed at providing economic growth without federalizing effective representation and military security. Nevertheless, economic federalization came along with policy challenges that – in case of a crisis shock – would require effective representation and the capacity to provide security for the entire union, i.e, to protect its external borders These policy challenges arise from two areas of European integration: the monetary union and the freedom of movement. 1. Monetary integration in the European Monetary Union (EMU) has been designed as an optimal currency area, in which the – at least in theory – the integration of monetary policy should not come along with asymmetric effects but should instead augment economic growth throughout the union. Nevertheless, this did not happen as expected

Several authors have argued that EMU is in fact no optimal currency area and that, due to its inflexibility, EMU has different growth effects in its member states (De Grauwe 2016)(Costa Cabral 2016, 1281), which have institutionalized different growth strategies (Hassel & Palier 2015). Due to different variety of political economies in the EMU, labor could not move freely, which resulted in fiscal and social problems, namely high budget imbalances and unemployment rates, especially in peripheral 8 Source: http://www.doksinet countries that were hit the most by the economic crisis (Hancké 2013). 2. The institutionalization of the single market came along with reforms (especially the SchengenAgreement) that allowed free movement of people between many EU member states and some non-EU member states, such as Norway and Switzerland. Furthermore, EU states harmonized refugee policy (Dublin agreements) and agreed on cooperating in the policies of police and internal security (Kasparek

2016). Once a crisis event occurs – such as the Euro crisis or the refugee crisis – these two dimensions of European integration pose policy challenges similar to the ones in federal states. Nevertheless, the EU is a case of “contested federalization in a non-state setting” (Fossum 2017, 487), in which the central level lacks legitimacy and policy capacity to respond the way federal governments do in times of crisis. This was no problem before the crisis because the contestation of federal powers was politicized relatively little in intergovernmental conflicts and party competition at the national level. As I will argue in the following, this changed once the union faces policy challenges that are related to crisis events and would have required effective temporary discretion at the European level. Other than in federal states, in the EU, the demand for effective temporary discretion at the European level led to extensive debates about the federal (European) order. Anti-crisis

policy and federal politics in the EU Once faced with crisis policy challenges, such as in the Euro crisis, federal states responded to the crisis with measures that temporarily reduced the discretion of the constituent units and increased central government’s competencies. It was beyond question that constituent units of the federation need to resolve their problems on their own. This strategy helped federal countries to resolve the crisis challenges because subnational government’s discretion did not result in federal conflicts. Of course, policymakers in the constituent units of federal countries responded with opportunism, i.e, they preferred and pursued (if possible) policy solutions that corresponded to their proper standard interests. This entailed that their policy preferences were different than the ones of other constituent units or the central government. For example, in Australia, New South Wales raised taxes although the federal government pursued an anti-cyclical

fiscal policy (Braun & Trein 2013b, 354). In the US, not all the states complied perfectly with the federal government regarding the implementation of 9 Source: http://www.doksinet the anti-crisis policies, notably the ARRA (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act) (Posner 2016, 197). Overall, during the financial crisis, the federal governments intervened to counteract the crisis with policy measures in the entire federation, for example in using temporary tax relieve measures and conditional grants that obliged the members states to invest in particular policies for example. These policies temporarily reduced the discretion of the member states because they had to follow the policies of the federal government, which, in turn, redistributed funds amongst the members of the federation. In other words, central government policy measures pooled sovereignty at the center temporarily but constituent units received compensation in terms of direct and indirect transfers and were bailed

out financially if necessary (Braun & Trein 2013b, 351)(Braun & Trein 2013a, 144-151). Overall, member states perceived the temporary reduction of their discretion as legitimate. Conflicts about such policies did not really turn into conflicts about the federal balance of power Although member states did not always comply with national policies, they regarded central governments’ measures as effective and legitimate in dealing with the crisis. As a consequence, desolidarization of members of the federation with one another remained weak, in other words, there is little evidence for a broad and fundamental erosion of solidarity amongst the members of the established federal countries (e.g, Australia, Germany, Switzerland, US) and none of these federations experienced a systemic crisis as a consequence of anti-crisis policies (Braun, Ruiz-Palmero & Schnabel 2017). There were of course exceptions For example, Belgium experienced a state crisis during the Euro-crisis, which

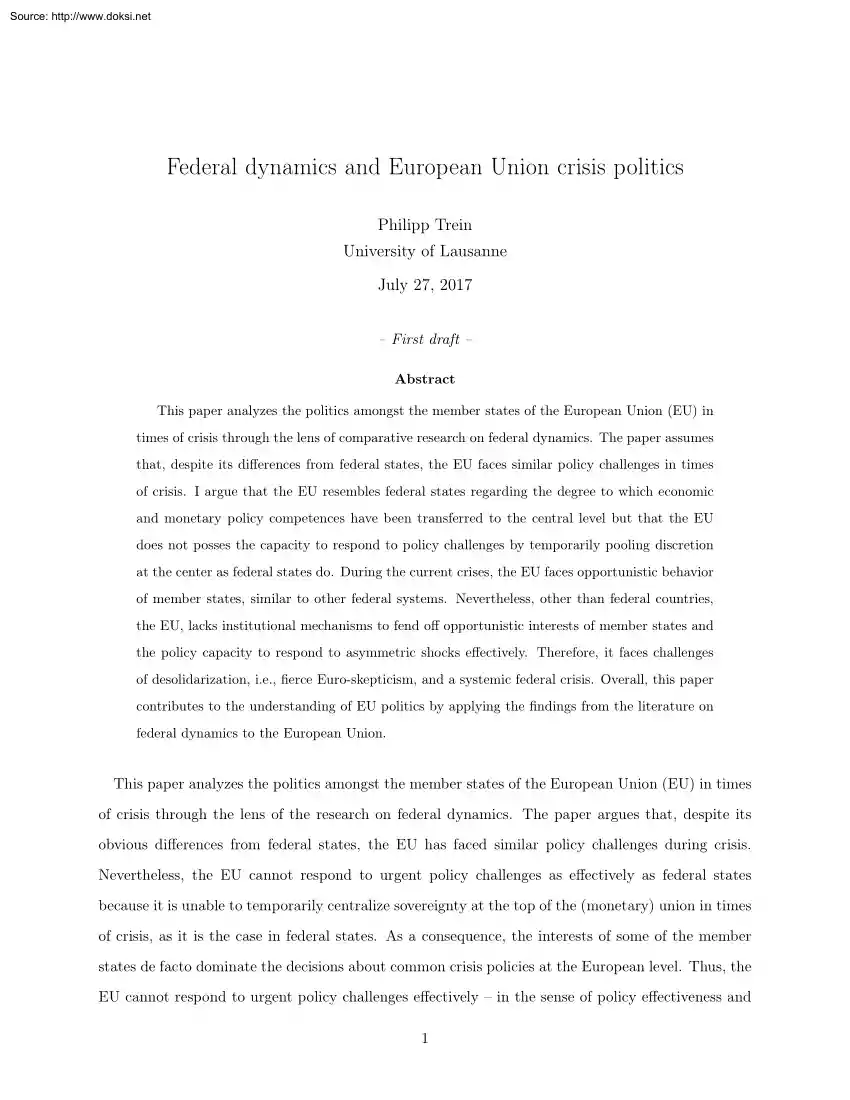

was also a crisis of federal relations that could only be resolved in decentralizing some policy competencies (?). In addition, the case of Catalonia’s secession campaign is somewhat an exception to the argument that federal states passed the crisis without large systemic conflicts. Nevertheless, Catalonia is an example for one constituent unit desiring to leave the federation. In addition, the conflict about the Catalan independence movement began prior to the economic and financial crisis of 2007 (?). The crisis and the anti-crisis policies of the federal government just fueled the pre-existing secessionist agenda Overall, apart from the mentioned exception the integrity of federal states was not put into question in the national discourse about anti-crisis policies (Braun & Trein 2014, 811). In other words, anti-crisis policies did not spill-over into federal politics and caused no federal crises, in the established federal states (Figure 1). In the EU, anti-crisis policies

affected federal politics in a different way than in federal states. Similar to federations, EU member states had opportunistic interests, which opposed some of the 10 Source: http://www.doksinet Figure 1: Federall dynamics in times of crisis Effective coping mechanism for opportunism: Crisis hits Weak desolidarization No federal crisis Federal states Strong desolidarization Federal crisis EU Opportunism of member states No effective coping mechanism for opportunism states to the others during the financial and economic crisis, the ensuing Euro crisis, and the migration crisis. In the Euro crisis, (Euro) states with a budgetary surplus respectively an export-led growth strategy had policy preferences opposed to the countries with a budget deficit and an importled growth strategy (Hancké 2013, Hassel & Palier 2015). In the migration crisis, to put it simply, preferences of EU member states where many refugees arrived opposed those of governments from countries that

were unaffected by the migration crisis (Geddes & Scholten 2016, 237-244). The decision on the policies dealing with the crisis pressures were decided largely in the EU commission, between the member states, and, in case of the Euro crisis, by involving the European Central Bank (ECB), and the IMF (International Monetary Fund). Especially, negotiations between governments of the member states were crucial in deciding about the policies taken at the EU level to counteract the crisis, whereas the direct involvement of the European and national parliaments remained weak, notably regarding the Euro crisis (Rittberger 2014, 1181). As a consequence, the anti-crisis policy solutions followed an intergovernmental logic and the compromise reflected the opposed interest structure of the various EU and EMU member states. 11 Source: http://www.doksinet In the Euro crisis, the majority of the Euro countries de facto voted for deficit countries, above all Greece, to adjust internally at

their own expenses (Walter 2016) – despite a formal consensual decision in the Euro group – a decision clearly at odds with the policy preferences of deficit countries. On the other hand, Greece, Germany, and other countries received rather little support regarding a redistribution of refugees who entered the EU during the refugee crisis, in 2015 (Carrera & Guild 2015). Overall, in the EU and the EMU, anti-crisis policies were decided according to a logic of intergovernmental cooperation and competition. The externality of the anti-crisis policies remained with the population of the EU/EMU member states that had a minority position in the intergovernmental game. Other than in federal states, the constitutional design of the EU did not allow for a temporal pooling of sovereignty at the centre to implement anti-crisis policies that redistributed the costs of the anti-crisis policies amongst the member states. Put differently, mechanisms for coping with member state opportunism

regarding anti-crisis policies were ineffective at the European level (Figure 1). Therefore, the EU experienced strong desolidarization during the crisis period, which resulted in a federal crisis and even the exit of an important member of the union (UK) (Figure 1). Indications for desolidarization and a federal crisis are the following. Firstly, the anti-crisis policies contained little solidarity with populations in the countries affected negatively by either the Euro crisis (Greece, Italy, or Spain) or the migration crisis (Germany, Greece). Secondly, strong desolidarization is visible in the loss of support for the EU in the population and the (further) strengthening of anti-Euro, anti-EU and anti-migrant parties and policy positions in many European countries (Treib 2014, Arzheimer 2015, Meijers 2015, Hobolt 2016). Thirdly, the vote for Brexit translated the the discursive and policy desolidarization into political facts and deepened the federal crisis of the European Union

(Hobolt 2016). Overall, other than in federal states, in the EU, the lack of institutional coping mechanisms for member states opportunism regarding anti-crisis policies was highly problematic. Solidarity with the populations of the countries that the crisis affected negatively remained low in the anti-crisis policy decisions. Therefore, desolidarization increased and the EU experienced a federal crisis 12 Source: http://www.doksinet Implications for EU policymaking and research The argument that I presented in this article has some implications for policymaking and research regarding the EU. In times of crisis, the current design of European institutions gives member states governments’ opportunistic preferences the last word, even if they result in policies with a very asymmetric distribution of policy externalities amongst member states. The central level – in this case the European institutions – lack the policy capacity and the legitimacy to pass policies that

distributes costs and benefits of anti-crisis policies amongst EU member states. The reason for this is the partial federalization of the EU (Fossum 2017), which consists in economic federalization but not in a federalization of representation and military security (Bednar 2009, 25-52). Once the Euro crisis hit and remained difficult to resolve, member states did not respond by another round of constitutional changes but aimed at resolving the crisis in adjusting the existing institutions of differential integration (Dawson & Witte 2016, Genschel & Jachtenfuchs 2016). This process is intentional and follows the institutional logic of European integration. Nevertheless, the price that the EU has to pay for its flexible constitution and limited statehood is that, in times of crisis, anti-crisis policies will come along almost certainly with a federal crisis, in which nationalist parties question European integration fundamentally. The main root of this dynamic is that EUwide

policy solutions are decided in principal in an intergovernmental arena that is very ineffective in its representative structure. Compared to federal states, the EU lacks the flexibility to set up anti-crisis policy responses, which compensate member states for negative crisis externalities, i.e, high unemployment or many refugees. Notably, the system of differentiated integration, which was designed to account for the diversity of European nations, is inflexible and inefficient when it comes to solve crisis policy challenges. To deal with the discussed problem in EU decision-making, several options are possible. According to federal theory (Bednar 2009, 25-52), the easiest solution would be to augment the policy capacity and democratic legitimacy at the central (European) level. Nevertheless, introducing strict majority decision at the European level, for example in a reenforced European parliament, would ignore the diversity of European polities and fuel tendencies towards a break-up

of the union rather than stabilizing the EU (Scharpf 2015, 393-395). Instead, reforms of the EU should focus on strengthening solidarity between EU member states 13 Source: http://www.doksinet and nations. Many federal systems have systems of fiscal equalization in order to counteract asymmetric crisis shocks In financial and economic crisis, horizontal and vertical redistribution was an important element of the anti-crisis policies, in federal states, which helped to fend off tendencies of desolidarization and federal crisis (Braun & Trein 2014, Trein & Braun 2016). In the EU, anti-crisis policies were lacking solidarity during the Euro crisis (Risse 2014) as well as the during the migration crisis (Scipioni 2017). There are, however, theoretical and empirical reasons for why it is necessary and possible to strengthen solidarity in the EU. 1. Firstly, theories of federalism and organizational relations suggest that solidarity is important for federal relations. For

example, state theories, such as the work by Johannes Althusius, point out that successful federal polities need to balance subsidiarity, solidarity and consensus (Hueglin 1999, 152-168). Furthermore, in following Hirschman’s organizational theory, Jachtenfuchs and Kasack suggest that we ought to consider exit and voice to understand dynamics in European integration (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017) but they do not focus on loyalty, which is the third concept put forward by Hirschman (Hirschman 1970). As I have demonstrated based on the analysis of anti-crisis policies and politics in federal states, solidarity and loyalty are important for federal stability in times of crisis but the incentive structures of the current EU institutions render it difficult to implement solidarity in anti-policies. 2. Secondly, for some time now, scholars have demanded to invest into a social investment pact in order to counteract the asymmetric effects of the crisis in Europe. In harkening back to an

analysis of the European political economy, researchers have argued that the EU needs social investment policies in order to replace the jobs lost during the crisis and to counteract social decline in the middle classes of European countries. Such policies would also strengthen the solidarity of citizens with the EU and other European nations and citizens and reduce the support for EU and Euro critical parties and movements (Vandenbroucke, Hemerijck, Palier et al. 2011) 3. Thirdly, there is some empirical evidence that EU citizens would at least to some extent support solidarity and thus carefully crafted policies that redistribute resources between European citizens. Thomas Risse points out that many citizens in the EU consider themselves as citizens of their nations and the EU at the same time (Risse 2014, 1209). This data can be interpreted 14 Source: http://www.doksinet that European citizens do not refuse more solidarity between European nations and that reforms of the EU

potentially could search to achieve more solidarity between member states. The discussed implications of the argument made in this paper are rather general. Nevertheless, the recent debate and suggestion for reforms of the EU take into consideration that more solidarity could help to stabilize the union against the backdrop of a potential Brexit scenario and further crises events (EU 2017). When putting reforms into place, policymakers should take into consideration the lessons from federal states, where solidarity between members of the federation is crucial to retain federal stability in times of crisis. Conclusion This paper analyzed federal politics and dynamics in the EU during times of crisis. In starting with insights from the comparative analysis of anti-crisis politics and policies in federal states, the paper examined how anti-crisis policies and politics affected the federal dynamics in the EU and the EMU. The article started with the assumption that the EU differs from

federal states because policy integration and centralization to the European level occurred in a flexible manner and representation accumulates at the European level in an indirect manner. Nevertheless, the paper assumed also that the EU resembles federal states regarding economic integration. Especially, the integration of monetary policy and the abolition of internal border controls created policy challenges for the EU that are similar to those in federal states. Once the EU faced a crisis situation, such as the Euro crisis or the refugee crisis, intergovernmental logic and opportunistic interests of member states dominated policy solutions. Other than federal states, the EU did not dispose of institutional mechanisms to cope with member states opportunism and it lacked the policy capacity to counteract the asymmetric effects of the Euro crisis and the refugee crisis. As a consequence, – relative to federal states – the EU experienced strong desolidarization, which resulted in a

political crisis of European integration. To avoid such scenarios in future crises, the article suggested to strengthen solidarity amongst EU members in future reforms of the union. 15 Source: http://www.doksinet References Arzheimer, Kai. 2015 “The afd: Finally a successful right-wing populist eurosceptic party for germany?” West European Politics 38(3):535–556. Bednar, Jenna. 2009 The Robust Federation: Principles of Design Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Benz, Arthur. 2017 “Patterns of multilevel parliamentary relations Varieties and dynamics in the EU and other federations.” Journal of European Public Policy 24(4):499–519 Benz, Arthur & Jörg Broschek. 2013a Conclusion Theorizing federal dynamics In Federal dynamics: Continuity, change, and the varieties of federalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press pp 366– 388. Benz, Arthur & Jörg Broschek, eds. 2013b Federal dynamics: continuity, change, and the varieties of federalism. Oxford: Oxford University

Press Boin, Arjen & Fredrik Bynander. 2015 “Explaining Success and Failure in Crisis Coordination” Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography 97(1):123–135. Bolleyer, Nicole. 2017 “Executive-legislative relations and inter-parliamentary cooperation in federal systems–lessons for the European Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 24(4):520–543 Börzel, Tanja A. 2005 “Mind the gap! European integration between level and scope” Journal of European Public Policy 12(2):217–236. Braun, Dietmar. 2009 “Constitutional change in Switzerland” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 39(2):314–340. Braun, Dietmar, Christian Ruiz-Palmero & Johanna Schnabel. 2017 Consolidation Policies in Federal States: Conflicts and Solutions. London and New York: Routledge Braun, Dietmar & Philipp Trein. 2013a Consolidation policies in federal countries In Staatstätigkeiten, Parteien und Demokratie: Festschrift für Manfred G Schmidt Wiesbaden: VS Verlag pp. 139–162

Braun, Dietmar & Philipp Trein. 2013b Economic crisis and federal dynamics In Federal Dynamics: Continuity, Change and the Varieties of Federalism, ed. Arthur Benz & Jörg Broschek Oxford: Oxford University Press pp. 343–365 Braun, Dietmar & Philipp Trein. 2014 “Federal Dynamics in Times of Economic and Financial Crisis.” European Journal of Political Research 53(4):803–821 Burgess, Michael. 2000 Federalism and European Union: the building of Europe, 1950-2000 London and New York: Routledge. Carrera, Sergio & Elspeth Guild. 2015 “Can the new refugee relocation system work? Perils in the Dublin logic and flawed reception conditions in the EU. CEPS Policy Brief No 332, October 2015 Thursday, 1 October 2015.” Colino, César & Angustias Hombrado. 2015 Besieged and paralyzed? The Spanish State facing the secessionist challenge in Catalonia and coping with the reform imperative. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft pp. 293–317 URL:

https://doi.org/105771/9783845272375-293 16 Source: http://www.doksinet Costa Cabral, Nazaré. 2016 “Which budgetary union for the E (M) U?” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54(6):1280–1295. Dawson, Mark & Floris Witte. 2016 “From balance to conflict: a new constitution for the EU” European Law Journal 22(2):204–224. De Grauwe, Paul. 2016 Economics of monetary union Oxford: Oxford University Press Dubuc, Alan. 2009 “Ottawa, provinces ally to quell a meltdown” Federations: Special Issue: Federations and the economic crisis pp 8–9, 35 EU. 2017 White paper on the future of Europe: Reflections and scenarios for the EU27 by 2025 Brussels: EU Commission. Fossum, John Erik. 2017 “Democratic federalization and the interconnectedness–consent conundrum” Journal of European Public Policy 24(4):486–498 Fossum, John Erik & Markus Jachtenfuchs. 2017 “Federal challenges and challenges to federalism Insights from the EU and federal states.” Journal of

European Public Policy 24(4):467–485 Geddes, Andrew & Peter Scholten. 2016 The politics of migration and immigration in Europe 2 ed. Los Angeles, London, New Dehli, Singapore, Washington DC, Melbourne: Sage Genschel, Philipp & Markus Jachtenfuchs. 2016 Conflict-minimizing integration: how the EU achieves massive integration despite massive protest. In The end of the Eurocrats dream : adjusting to European diversity, ed Damien Chalmers, Markus Jachtenfuchs & Philipp Genschel Cambridge: Cambridge University Press pp. 166–189 Gerber, Elisabeth R & Ken Kollman. 2004 “IntroductionAuthority migration: Defining an emerging research Agenda” PS: Political Science & Politics 37(3):397–401 Hancké, Bob. 2013 Unions, central banks, and EMU: Labour market institutions and monetary integration in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press Hassel, Anke & Bruno Palier. 2015 “National growth strategies and welfare state reforms” CES Annual Conference, Paris, July.

Hirschman, Albert O. 1970 Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Vol 25 Cambridge: Harvard University Press Hobolt, Sara B. 2016 “The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent” Journal of European Public Policy 23(9):1259–1277. Hooghe, Liesbet & Gary Marks. 2003 “Unraveling the Central State, but How? Types of Multi-Level Governance.” The American Political Science Review 97(2):233–243 Hueglin, Thomas O. 1999 Early modern concepts for a late modern world: Althusius on community and federalism. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press Hueglin, Thomas O. & Alan Fenna 2015 Comparative Federalism: A Systematic Inquiry New York, Ontario: University of Toronto Press. Hvidsten, Andreas H & Jon Hovi. 2015 “Why no twin-track Europe? Unity, discontent, and differentiation in European integration.” European Union Politics 16(1):3–22 17 Source: http://www.doksinet Jachtenfuchs, Markus & Christiane Kasack.

2017 “Balancing sub-unit autonomy and collective problem-solving by varying exit and voice. An analytical framework” Journal of European Public Policy 24(4):598–614. Kasparek, Bernd. 2016 Complementing Schengen: The Dublin System and the European Border and Migration Regime. In Migration Policy and Practice, ed Harald Bauder & Christian Matheis Springer pp. 59–78 Kelemen, R Daniel. 2009 The rules of federalism: Institutions and regulatory politics in the EU and beyond. Harvard: Harvard University Press Leuffen, Dirk, Berthold Rittberger & Frank Schimmelfennig. 2012 Differentiated integration: explaining variation in the European Union Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Majone, Giandomenico. 1994 “The rise of the regulatory state in Europe” West European Politics 17(3):77–101. Majone, Giandomenico. 2009 Dilemmas of European integration: the ambiguities and pitfalls of integration by stealth. Oxford: Oxford University Press Meijers, Maurits J. 2015 “Contagious

Euroscepticism: The impact of Eurosceptic support on mainstream party positions on European integration” Party Politics p 1354068815601787 Niesen, Peter. 2017 “The ‘Mixed’Constituent Legitimacy of the European Federation” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 55(2):183–192. Posner, Paul L. 2016 "Accountability under Stress The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. In Governing Under Stress: The Implementation of Obama’s Economic Stimulus Program, ed. Timothy J Conlan, Paul L Posner & Priscilla M Regan Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press pp. 183–208 Risse, Thomas. 2014 “No demos? Identities and public spheres in the euro crisis” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52(6):1207–1215. Rittberger, Berthold. 2014 “Integration without representation? The European Parliament and the reform of economic governance in the EU.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52(6):1174–1183. Scharpf, Fritz W. 1999 Governing in Europe: Effective and

democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press. Scharpf, Fritz W. 2015 “After the crash: A perspective on multilevel European democracy” European Law Journal 21(3):384–405 Schimmelfennig, Frank, Dirk Leuffen & Berthold Rittberger. 2015 “The European Union as a system of differentiated integration: interdependence, politicization and differentiation.” Journal of European Public Policy 22(6):764–782. Schimmelfennig, Frank & Thomas Winzen. 2014 “Instrumental and constitutional differentiation in the European Union.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52(2):354–370 Scipioni, Marco. 2017 “Failing forward in EU migration policy? EU integration after the 2015 asylum and migration crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy pp 1–19 18 Source: http://www.doksinet Trechsel, Alexander H. 2005 “How to federalize the European Union and why bother” Journal of European Public Policy 12(3):401–418. Treib, Oliver. 2014 “The voter says no, but nobody listens:

causes and consequences of the Eurosceptic vote in the 2014 European elections” Journal of European Public Policy 21(10):1541–1554 Trein, Philipp & Dietmar Braun. 2016 “How do fiscally decentralized federations fare in times of crisis? Insights from Switzerland.” Regional & Federal Studies 26(2):199–220 Vandenbroucke, Frank. 2017 Social policy in a monetary union: puzzles, paradoxes and perspectives In The End of Postwar and the Future of Europe – Essays on the work of Ian Buruma, ed. Marc Boone, Gita Deneckere & Jo Tollebeek. Verhandelingen van de KVAB voor Wetenschappen en Kunsten Uitgeverij Peeters. Vandenbroucke, Frank, Anton Hemerijck, Bruno Palier et al. 2011 “The EU needs a social investment pact.” Observatoire Social Européen Paper Series, Opinion Paper 5 Walter, Stefanie. 2016 “Crisis politics in Europe: Why austerity is easier to implement in some countries than in others.” Comparative Political Studies 49(7):841–873 Wasserfallen, Fabio.

2014 “Political and economic integration in the EU: The case of failed tax harmonization.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52(2):420–435 19

member states and the policy capacity to respond to asymmetric shocks effectively. Therefore, it faces challenges of desolidarization, i.e, fierce Euro-skepticism, and a systemic federal crisis Overall, this paper contributes to the understanding of EU politics by applying the findings from the literature on federal dynamics to the European Union. This paper analyzes the politics amongst the member states of the European Union (EU) in times of crisis through the lens of the research on federal dynamics. The paper argues that, despite its obvious differences from federal states, the EU has faced similar policy challenges during crisis. Nevertheless, the EU cannot respond to urgent policy challenges as effectively as federal states because it is unable to temporarily centralize sovereignty at the top of the (monetary) union in times of crisis, as it is the case in federal states. As a consequence, the interests of some of the member states de facto dominate the decisions about common

crisis policies at the European level. Thus, the EU cannot respond to urgent policy challenges effectively – in the sense of policy effectiveness and 1 Source: http://www.doksinet democratic effectiveness –, which results in a systemic destabilization of union due to desolidarisation amongst the member states. In other words, the price of flexible and differentiated integration and monetary solidarity is that the EU lacks an effective governance mode to respond to crises policy challenges without risking desolidarization and a systemic crisis of the EU. Federalism has been a core topic to the analysis of European integration. Although European integration has taken above all a path of economic and differentiated political integration (Leuffen, Rittberger & Schimmelfennig 2012, Schimmelfennig, Leuffen & Rittberger 2015), many researchers have analyzed the EU under the aspects of federalism.1 In this literature, there is consensus that the EU is different from federal

states because important elements of state sovereignty, such as the control over the military, taxation, and redistribution remain locked in almost entirely at the level of the member states (Burgess 2000, Trechsel 2005, Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017). To account for difference between European integration and federalization, scholars have referred to multilevel governance (Hooghe & Marks 2003), regulatory federalism (Kelemen 2009), or integration by stealth (Majone 2009) just to name a few concepts that figure prominently in the debate. Against the backdrop of the economic and ensuing political crisis of the EU, researchers have made a number of new contributions that study the EU under the promises of federalism. This research outlines the problem of constitutional legitimacy in the European federation (Niesen 2017), the potential of a fiscal union (Costa Cabral 2016), democratic representation (Benz 2017, 515), parliamentary activism in the EU compared to federal states

(Bolleyer 2017, 535-536) as well as the political dynamics between the member states and the EU (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017). This paper contributes to this literature by undertaking an analysis that analyzes the federal dynamics in the European Union. In harkening back to the literature on federal dynamics in general (Bednar 2009, Benz & Broschek 2013b) and to the works on dynamics of federal states especially (Braun & Trein 2013b, Braun & Trein 2014, Trein & Braun 2016), this article analyzes how EU institutions shape member states’ policy preferences in dealing with asymmetric crisis events that require an immediate policy response for the entire union. The paper assumes that due to the economic, monetary and (partial) political integration, the EU faces policy challenges that are similar to the ones in federal states. In federal countries, even in the most decentralized federations, such as Canada, Switzerland or the U.S, the central government responds to

crisis events, even if 1 For a detailed literature overview read also: (Fossum & Jachtenfuchs 2017). 2 Source: http://www.doksinet these policy responses require a temporary centralization of competencies. In other words, anticrisis policies come along with a temporarily limited pooling of the otherwise shared sovereignty at the central level, in order to deal with the crisis problem, such as an economic crisis, even if pooling of sovereignty interferes with the opportunistic interests of the member states. Temporary centralization helps to avoid that the desolidarization tendencies in the federation, which might come along with crisis events, turn into systemic crises that call into question federal integration entirely. I argue that differentiated political integration, which distinguishes the EU and from federal states, does not allow for effective temporary centralization of powers in order to deal with crisis pressures. In fact, if fast and efficient policy responses are

needed, decision making at the EU level will be concentrated amongst the member states governments and the European Commission. These actors lack a) democratic legitimacy and power as in the case of the European Commission or b) are guided by the opportunistic interests of the majority of the member states rather than by dealing with the policy problem from the perspective of the union as a whole. Two examples illustrate this argument: firstly, intergovernmental competition and eventually the interests of the creditor countries dominated de facto the bailout packages for Greece and other crisis countries without taking into consideration the social consequences of these policies. Secondly, in the refugee crisis, an effective redistribution of the refugees amongst member states failed again due to the intergovernmental conflicts. In short – other than in federal states – the EU lacks an institutional mechanism to cope effectively with member state opportunism. As a consequence,

desolidarization increased amongst members of the EU and the Eurozone, and voters increased their support for EUcritical parties. The yes-vote for Brexit can be interpreted as another symptom of this mechanism This paper teaches us that differentiated integration in the EU does not allow for effective temporary centralization. In the EU, despite the economic and political integration, sovereignty is inflexible and cannot be pooled at the central level in order to deal with pressing policy challenges such as economic crises. Thus, unless the EU finds a way to respond to crisis problems in a way that is effective with regard to problem-solving and democratic legitimacy, any new crises is likely to result in desolidarization and a systemic crises of the EU. To remedy this problem, the paper suggests that reforms of the EU should strengthen solidarity amongst the members of the union. 3 Source: http://www.doksinet Federal dynamics in times of crisis The theoretical approach this paper

uses to analyze federal dynamics in EU politics during times of crisis is based on the research on federal dynamics. In this literature, researchers have focused on the variation between federal states, the dynamics within federal systems (Benz & Broschek 2013a, 367-372), and on the institutional conditions under which federations remain stable or even break up (Bednar 2009, 95-127). In the research on the EU and federalism, authors have referred to the mentioned literature but without an explicit focus on instability and stability of the EU in the light of the Union’s federal dynamics (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017). Nevertheless, the research on anticrisis policies and politics in federal states provides important insights for understanding politics of crisis in the EU and its consequences of federal stability. Therefore, this article starts from the literature on institutional and policy-related dynamics in federal states during the economic, financial, and debt crisis (Braun

& Trein 2013a, Braun & Trein 2013b, Braun & Trein 2014, Braun, Ruiz-Palmero & Schnabel 2017). This literature has analyzed how federal states responded to the policy challenges that emerged as a consequence of the financial and economic as well as the ensuing debt crisis after 2007. The research has demonstrated that – once the economy went down and debt rates augmented – the federal government took action in order to deal with these crisis induced policy challenges. Against the crisis background, national governments responded with economic stimulus programs that entailed for example financial transfers to subnational governments (Braun & Trein 2013b, 351) as well as measures to bail out subnational governments and to enforce budgetary discipline in the future (Braun & Trein 2013a, 144-151). Subnational governments for their part pursued their own policies, which corresponded sometimes with the measures of the national government’s measures, but there is

also evidence for opportunism (Braun & Trein 2013b, 351)(Braun & Trein 2014, 811), i.e, some subnational governments pursued policies at odds with the federal governments’ measures or refused to implement central government’s policies because they considered them to be against their interests Furthermore, there are instances of desolidarization, which means that some of the member states in federations questioned solidarity with other members of the federation, for example by requesting reforms of the fiscal equalization system or by considering to leave the federal state (Braun & Trein 2014, 811). In all federations, the interventions of the central government where temporary and did not 4 Source: http://www.doksinet results in debates of principle about the federal order. Belgium, Canada, and Spain are somewhat exceptional to this because in these countries the crisis came along with debates about the legitimacy of the federal order and the anti-crisis policies

coincided with federal conflicts (Braun & Trein 2014, 811). For example, in Canada, there were debates about the consequences of the demand crisis for fiscal equalization (Dubuc 2009) and in Spain, the crisis fueled the conflict between Catalonia and the centre (Colino & Hombrado 2015). Nevertheless, overall, federal states managed the crisis well – in the sense that there is no instance of a federation breaking up. Temporary interventions by central governments, the common control of over-borrowing, and the presence of stabilizing institutions to cope with constituent units’ opportunism, i.e, safeguards (Braun, Ruiz-Palmero & Schnabel 2017) helped federal countries to retain institutional stability, during the crisis period. This literature on federal dynamics in European crisis provides us with the following insights that are important for analyzing the politics of the European Union and its member states during times of crisis. 1. In political systems where two or

more levels of government share sovereignty, external crisis events results in opportunistic behavior of the member states of the federation that seek to defend their interests against other member states and the federal government. 2. In federal states, there was a compromise that the members of the federation and the federal government should resolve the crisis together As a consequence, central government put forward the first policy responses to the crisis, which entailed a temporal centralization of discretion to the federal level. In other words, anti-crisis policies contained a pooling of sovereignty at the central level in order to meet the demand for problem solving. Member states did not challenge the temporary shift of discretion to the centre to deal with the crisis. On the other hand, anti-crisis policies did not result in permanent authority migration (Gerber & Kollman 2004) to the central level. 3. Member states of federal countries did not generally challenge the

temporary shift of policy discretion to the centre during the crisis. Overall, conflicts between the member states of the federation and the central government about crisis policies did not spill-over into federal conflicts about the balance of power in the federation in general (Braun, Ruiz-Palmero & Schnabel 2017, 34). Furthermore, the temporary centralization assured fast problem solv5 Source: http://www.doksinet ing and avoided that opportunistic interests of member states captured federal politics and that desolidarizing tendencies between member states turned into systemic conflicts in the federation. The EU and federal states: differences and similarities The EU is similar to and different from federal states. According to Jenna Bednar, there are three dimensions of federalization that are relevant to federal states’ regarding the allocation of competencies between the central level and the member states: the provision of military security, economic growth, and

effective representation. Federal states try to achieve these goals by centralizing powers at the national level, decentralizing competencies to the subnational level or by sharing powers between levels of government (Bednar 2009, 25-52). In keeping in mind these three main goals of government – military security, economic growth, and effective representation – allows us to assess how the EU resembles to and differs from federal states. Differences between the EU and federal states In comparison to other federal states, the EU is a very decentralized political system. This is visible in the socioeconomic differences between the EU and federations. For example, the diversity in median household income and inequality is much higher than in the most decentralized federations, such as the U.S (Vandenbroucke 2017) In terms of the centralization of political powers, the EU differs from other federal states as it has no own major taxation power, such as an income tax, and military

affairs remain almost entirely in the hands of the member states (Costa Cabral 2016, 1285)(Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017, 600). As a consequence direct redistribution in the EU needs to be horizontal, which is something that is already immensely complicated in federal states where the federal government possesses a considerable amount of proper resources and horizontal fiscal equalization is often mixed with vertical transfers, for example in Switzerland (Braun 2009). Therefore, any horizontal redistribution should be an immensely complicated undertaking in the EU. Other than in federal states, the “EU’s material constitution is also highly malleable” (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017, 601), which is something that did not occur unintended and makes the EU different from federal states. One reason for this situation is that the EU constitution has remained highly 6 Source: http://www.doksinet contested, as the failure of the Constitutional Treaty of 2005 shows (Jachtenfuchs

& Kasack 2017, 601). The Europeanization literature has coined the term differentiated integration (Schimmelfennig & Winzen 2014, Hvidsten & Hovi 2015) to account for the particular constitutional situation of the EU. Rather than fixing a broad constitutional contract, member states continued to voice their preferences over the dilemma between common problem solving, i.e, centralization of competencies, and to retain autonomy in a differentiated manner. In other words, member states decide about their preferences for transferring power to the EU or not regarding specific policy issues, such as the Single Resolution Fund or European Stability Mechanism (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017, 601). Thus European integration follows a path of differentiated political integration (Schimmelfennig, Leuffen & Rittberger 2015, 774-779). Put differently, there is an integration of specific policies, such as regarding the common market, but little broad constitutional integration as in

federal states. Eventually, the EU differs from federal states concerning political representation. The EU has no party system that is highly centralized as most federal states do (Jachtenfuchs & Kasack 2017, 600). In addition, the link between citizens and the representatives at the European level is rather weak and indirect. Compared to first parliamentary chambers in other federal states, the competencies of the European parliament are weak (Hueglin & Fenna 2015), and so is its input legitimacy for unified European policy solutions. Although the community method emphasizes the power of European institutions to solve common problems, intergovernmental coordination of member states remains the most important mode of decision making (Scharpf 1999, Majone 2009). Other than in federal states, EU member states have a very strong control of political decisions at the federal level. In other words, there is no institution to counterbalance the strong influence of the member

states’ governments in decision-making at the federal (EU) level (Hueglin & Fenna 2015). In times of crisis, the institutional setting at the EU level – theoretically – opens the door to transferring opportunistic interests of some member states into policies at the expenses of other members states in the shadow of consensual decision making in the European Council. This is particularly the case when fast problem solving is required, such as in the case of the economic and financial crisis or the migration crisis. Even in standard federal states, in which sovereignty can be pooled at the national level, coordination of anti-crisis policies is already quite complicated (Boin & Bynander 2015). Thus, we can expect that is even more difficult at the European level 7 Source: http://www.doksinet Similarities between the EU and federal states Despite the differences between the EU and federal states, there are some similarities between the EU and federations. Against the

background that the EU is a “regulatory state” (Majone 1994), researchers have argued that EU federalism is above all regulatory federalism (Kelemen 2009, 1-2), in which the federal state provides above all rules as regulatory unification but direct redistribution of tax money between member states of the federation does not play an important role as tax harmonization (Wasserfallen 2014) and transfer to taxation competencies to the European level remain narrow. Therefore, the EU is similar to federal states regarding its regulatory unification During the process of regulatory federalization (Leuffen, Rittberger & Schimmelfennig 2012), national states transferred competencies to the central, i.e, the European, level of government, which were mostly in the field of regulation of common market processes (Schimmelfennig, Leuffen & Rittberger 2015, 768)(Börzel 2005, 221). Against the background the three dimensions of federalism laid out by Jenna Bednar (Bednar 2009, 25-52),

the EU underwent a process of federalization – understood in the in the sense of transferring sovereignty to a central level – in the economic arena. Put differently: federalization aimed at providing economic growth without federalizing effective representation and military security. Nevertheless, economic federalization came along with policy challenges that – in case of a crisis shock – would require effective representation and the capacity to provide security for the entire union, i.e, to protect its external borders These policy challenges arise from two areas of European integration: the monetary union and the freedom of movement. 1. Monetary integration in the European Monetary Union (EMU) has been designed as an optimal currency area, in which the – at least in theory – the integration of monetary policy should not come along with asymmetric effects but should instead augment economic growth throughout the union. Nevertheless, this did not happen as expected

Several authors have argued that EMU is in fact no optimal currency area and that, due to its inflexibility, EMU has different growth effects in its member states (De Grauwe 2016)(Costa Cabral 2016, 1281), which have institutionalized different growth strategies (Hassel & Palier 2015). Due to different variety of political economies in the EMU, labor could not move freely, which resulted in fiscal and social problems, namely high budget imbalances and unemployment rates, especially in peripheral 8 Source: http://www.doksinet countries that were hit the most by the economic crisis (Hancké 2013). 2. The institutionalization of the single market came along with reforms (especially the SchengenAgreement) that allowed free movement of people between many EU member states and some non-EU member states, such as Norway and Switzerland. Furthermore, EU states harmonized refugee policy (Dublin agreements) and agreed on cooperating in the policies of police and internal security (Kasparek

2016). Once a crisis event occurs – such as the Euro crisis or the refugee crisis – these two dimensions of European integration pose policy challenges similar to the ones in federal states. Nevertheless, the EU is a case of “contested federalization in a non-state setting” (Fossum 2017, 487), in which the central level lacks legitimacy and policy capacity to respond the way federal governments do in times of crisis. This was no problem before the crisis because the contestation of federal powers was politicized relatively little in intergovernmental conflicts and party competition at the national level. As I will argue in the following, this changed once the union faces policy challenges that are related to crisis events and would have required effective temporary discretion at the European level. Other than in federal states, in the EU, the demand for effective temporary discretion at the European level led to extensive debates about the federal (European) order. Anti-crisis

policy and federal politics in the EU Once faced with crisis policy challenges, such as in the Euro crisis, federal states responded to the crisis with measures that temporarily reduced the discretion of the constituent units and increased central government’s competencies. It was beyond question that constituent units of the federation need to resolve their problems on their own. This strategy helped federal countries to resolve the crisis challenges because subnational government’s discretion did not result in federal conflicts. Of course, policymakers in the constituent units of federal countries responded with opportunism, i.e, they preferred and pursued (if possible) policy solutions that corresponded to their proper standard interests. This entailed that their policy preferences were different than the ones of other constituent units or the central government. For example, in Australia, New South Wales raised taxes although the federal government pursued an anti-cyclical

fiscal policy (Braun & Trein 2013b, 354). In the US, not all the states complied perfectly with the federal government regarding the implementation of 9 Source: http://www.doksinet the anti-crisis policies, notably the ARRA (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act) (Posner 2016, 197). Overall, during the financial crisis, the federal governments intervened to counteract the crisis with policy measures in the entire federation, for example in using temporary tax relieve measures and conditional grants that obliged the members states to invest in particular policies for example. These policies temporarily reduced the discretion of the member states because they had to follow the policies of the federal government, which, in turn, redistributed funds amongst the members of the federation. In other words, central government policy measures pooled sovereignty at the center temporarily but constituent units received compensation in terms of direct and indirect transfers and were bailed

out financially if necessary (Braun & Trein 2013b, 351)(Braun & Trein 2013a, 144-151). Overall, member states perceived the temporary reduction of their discretion as legitimate. Conflicts about such policies did not really turn into conflicts about the federal balance of power Although member states did not always comply with national policies, they regarded central governments’ measures as effective and legitimate in dealing with the crisis. As a consequence, desolidarization of members of the federation with one another remained weak, in other words, there is little evidence for a broad and fundamental erosion of solidarity amongst the members of the established federal countries (e.g, Australia, Germany, Switzerland, US) and none of these federations experienced a systemic crisis as a consequence of anti-crisis policies (Braun, Ruiz-Palmero & Schnabel 2017). There were of course exceptions For example, Belgium experienced a state crisis during the Euro-crisis, which

was also a crisis of federal relations that could only be resolved in decentralizing some policy competencies (?). In addition, the case of Catalonia’s secession campaign is somewhat an exception to the argument that federal states passed the crisis without large systemic conflicts. Nevertheless, Catalonia is an example for one constituent unit desiring to leave the federation. In addition, the conflict about the Catalan independence movement began prior to the economic and financial crisis of 2007 (?). The crisis and the anti-crisis policies of the federal government just fueled the pre-existing secessionist agenda Overall, apart from the mentioned exception the integrity of federal states was not put into question in the national discourse about anti-crisis policies (Braun & Trein 2014, 811). In other words, anti-crisis policies did not spill-over into federal politics and caused no federal crises, in the established federal states (Figure 1). In the EU, anti-crisis policies

affected federal politics in a different way than in federal states. Similar to federations, EU member states had opportunistic interests, which opposed some of the 10 Source: http://www.doksinet Figure 1: Federall dynamics in times of crisis Effective coping mechanism for opportunism: Crisis hits Weak desolidarization No federal crisis Federal states Strong desolidarization Federal crisis EU Opportunism of member states No effective coping mechanism for opportunism states to the others during the financial and economic crisis, the ensuing Euro crisis, and the migration crisis. In the Euro crisis, (Euro) states with a budgetary surplus respectively an export-led growth strategy had policy preferences opposed to the countries with a budget deficit and an importled growth strategy (Hancké 2013, Hassel & Palier 2015). In the migration crisis, to put it simply, preferences of EU member states where many refugees arrived opposed those of governments from countries that

were unaffected by the migration crisis (Geddes & Scholten 2016, 237-244). The decision on the policies dealing with the crisis pressures were decided largely in the EU commission, between the member states, and, in case of the Euro crisis, by involving the European Central Bank (ECB), and the IMF (International Monetary Fund). Especially, negotiations between governments of the member states were crucial in deciding about the policies taken at the EU level to counteract the crisis, whereas the direct involvement of the European and national parliaments remained weak, notably regarding the Euro crisis (Rittberger 2014, 1181). As a consequence, the anti-crisis policy solutions followed an intergovernmental logic and the compromise reflected the opposed interest structure of the various EU and EMU member states. 11 Source: http://www.doksinet In the Euro crisis, the majority of the Euro countries de facto voted for deficit countries, above all Greece, to adjust internally at

their own expenses (Walter 2016) – despite a formal consensual decision in the Euro group – a decision clearly at odds with the policy preferences of deficit countries. On the other hand, Greece, Germany, and other countries received rather little support regarding a redistribution of refugees who entered the EU during the refugee crisis, in 2015 (Carrera & Guild 2015). Overall, in the EU and the EMU, anti-crisis policies were decided according to a logic of intergovernmental cooperation and competition. The externality of the anti-crisis policies remained with the population of the EU/EMU member states that had a minority position in the intergovernmental game. Other than in federal states, the constitutional design of the EU did not allow for a temporal pooling of sovereignty at the centre to implement anti-crisis policies that redistributed the costs of the anti-crisis policies amongst the member states. Put differently, mechanisms for coping with member state opportunism

regarding anti-crisis policies were ineffective at the European level (Figure 1). Therefore, the EU experienced strong desolidarization during the crisis period, which resulted in a federal crisis and even the exit of an important member of the union (UK) (Figure 1). Indications for desolidarization and a federal crisis are the following. Firstly, the anti-crisis policies contained little solidarity with populations in the countries affected negatively by either the Euro crisis (Greece, Italy, or Spain) or the migration crisis (Germany, Greece). Secondly, strong desolidarization is visible in the loss of support for the EU in the population and the (further) strengthening of anti-Euro, anti-EU and anti-migrant parties and policy positions in many European countries (Treib 2014, Arzheimer 2015, Meijers 2015, Hobolt 2016). Thirdly, the vote for Brexit translated the the discursive and policy desolidarization into political facts and deepened the federal crisis of the European Union

(Hobolt 2016). Overall, other than in federal states, in the EU, the lack of institutional coping mechanisms for member states opportunism regarding anti-crisis policies was highly problematic. Solidarity with the populations of the countries that the crisis affected negatively remained low in the anti-crisis policy decisions. Therefore, desolidarization increased and the EU experienced a federal crisis 12 Source: http://www.doksinet Implications for EU policymaking and research The argument that I presented in this article has some implications for policymaking and research regarding the EU. In times of crisis, the current design of European institutions gives member states governments’ opportunistic preferences the last word, even if they result in policies with a very asymmetric distribution of policy externalities amongst member states. The central level – in this case the European institutions – lack the policy capacity and the legitimacy to pass policies that