A doksi online olvasásához kérlek jelentkezz be!

A doksi online olvasásához kérlek jelentkezz be!

Nincs még értékelés. Legyél Te az első!

Legnépszerűbb doksik ebben a kategóriában

Tartalmi kivonat

Executive Talent Assessment and Selection: A Literature Review Stephen J. Zaccaro George Mason University October 20, 2008 2 Executive Talent Assessment and Selection: A Literature Review Overview of Contents Introduction: The Need for Better Executive Talent Acquisition Definition of Executive Position Requirements Delineation of Requisite Executive Attributes Recruitment of Position Candidates Assessment and Evaluation of Executive Candidates Making Executive Selection Decisions Conclusion: Implications and Recommendations This paper describes research on the steps and procedures of executive talent acquisition. I will review and summarize studies in the scholarly literature as well as research reports and assessment tools and products currently used by a range of companies that specialize in executive selection. I will specifically examine five components of executive talent acquisition: defining executive position requirements, delineating desired

candidate attributes, recruiting executive candidates, assessing and evaluating candidates, and deciding on the final choice for an executive position. The failure rate for top executives is inordinately high – the cause resides primarily in the failure of companies do follow appropriate and best practices for each of these components. For example, good selection practices require that all contributors to the selection decision have a shared understanding of what the new executive will be required to do once in position. Yet, many executive selection committees do not chose do have formal discussions around these requirements. Or, if they do, they focus on how former position holders acted, and 3 define future position requirements in the same way, or opposite to those in the past. There is rarely attention paid to how the position might change as the organization changes. As another example, executive selection companies often use ways of gathering information about candidates

that are among the least effective in terms of predicting who might best perform in the executive role. Thus, the executive talent acquisition process, as practiced by many companies, is likely to be seriously flawed in at least one if not more of the aforementioned components. In this paper, I summarize what we know about each of these components, including some recommendations for future research and practice. Introduction: The Need for Better Executive Talent Acquisition Why place a strong (and costly, if done correctly) emphasis on executive talent management: Because executive leaders represent vital contributors to organizational success. While people believe this observation intuitively, researchers using utility analyses have confirmed such contributions in empirical terms. For example, Weiner and Mahoney (1981) reported that executive succession in 193 organizations over a 19 year period accounted for approximately 44% and 47% in profit margins and stock process, respectively.

Barrick, Day, Lord, and Alexander (1991) calculated the financial impact of executive leadership in 132 organizations over a 15-year period; they found that organizations with high performing executives accrued an average of $25 million in value during the typical tenure of such executives. More recently, Hogan and Kaiser (2005) citing research by Joyce, Nohria, and Roberson (2003) noted that “CEOs account for about 14% of the variance in firm performance [while] industry sector accounts for 19% of that variance). Collins (2001) in his study of 11 companies who exhibited 15 years of below average growth (for their business sector) followed 4 by 15 years of above average growth found that the first step in the process of going from “good to great” was the hiring of the right top executives. So, in the words of Hambrick & Mason (1994, p. 194), “top executives matter” Yet despite this importance, the incidence of CEO and executive failures suggest that organizations are

not tending closely enough to the selection of effective executives. Failure rates among senior executives have persisted at high levels. DeVries (1993) noted that “achieving a 50% success rate in hiring for these positionsmay be as good as it gets” (p. 3) Indeed, regarding CEOs, failure rates appear to be have been increasing exponentially over the last 10 years. Bennis and O’Toole (2000), describing this phenomenon as “CEO churning,” summarized from business research that “CEOs appointed after 1985 [were] three times more likely to be fired than CEOs who were appointed before that date (p. 171) Booz, Allen and Hamilton, a company that has been documenting trends in CEO departures among 2,500 of the largest public companies in the world since 1995, has noted that the rate of CEO turnovers from all causes (forced dismissals, retirement, mergers) increased significantly between 1995 and 2002, from 6% to about 10-11% (Lucier, Schuyt, & Spiegel, 2003). After 2003, this

rate jumped to about 14 15%, with forced dismissals of CEOs jumped from about 1% in the 1990s to 42% in 2007 (Karlsson, Nelison, & Webster, 2008). Executives at all top levels of organizations are also failing earlier after being promoted, with reported failure rates in the first year and half in position ranging from 16-40% (Crowley, 2004; Liberman, 2001; Lucier, et al., 2003) Given the utility of successful executives for organizational effectiveness, such failure rates can be disastrous; accordingly, their reduction needs to be a top priority for today’s organization. Indeed, recent surveys have noted increased concern by CEOs and boards of directors on succession planning. One survey of public-company CEOs indicated that they 5 ranked CEO succession as second in importance to their boards of directors, behind overall corporate performance, but ahead of strategic planning and corporate governance (Biggs, 2004). A survey of top executives by the Society of Human Research

Management found that 75% of them cited succession planning as their most significant challenge for the future, while over two thirds cited recruiting, selecting and retaining talented employees as among the next most important challenges (Society of Human Research Management, 2007). Progress in this area needs to begin with a better understanding of those factors that account for CEO selection failures. Researchers and business scholars have offered several potential reasons for these failures. One explanation pertains to the often procrastinating tendencies of current executives when thinking about future CEO succession. In the soaring temporal exigencies that characterize the typical operating environment for today’s organizations, few executives and boards of directors put consideration of their future replacements high among their immediate priorities (Muller, 2004). Thus, the work of thinking through the needs and processes of executive selection becomes relegated as a

secondary or tertiary issue. Also, executive succession means the uncomfortable feeling of confronting one‘s own career mortality (Swain & Turpin, 2005). Thus, CEOs, the individuals generally most responsible for putting into motion executive succession processes, are not likely to be highly motivated to approach the topic. Boards of directors can mitigate this reluctance by initiating their own processes. However, if the board is composed mostly of internal executives placed into position by the CEO, or strongly loyal to him or her, they may share the CEO’s reluctance to consider succession plans. Perhaps the most significant and likely reason for the failure of CEO selection and succession processes refers to fact that most executive do not posses, or use, the knowledge and 6 skills needed to accomplish successful executive selection (DeVries, 1993; Hogan & Kaiser, 2008; Lawler & Feingold, 1997; Sessa & Taylor, 2000a). Drucker (1985, p 22) noted that “by and

large, executive make poor promotion and staffing decisions. By all accounts, their batting average is no better than .333In no other area of management would we put up with such miserable performance.” Strategic decision-making typically relies upon a careful collection of problem related data and facts, thorough analysis of the data, with the specification of solution alternatives, and a scrupulous and orderly weighing of the costs and benefits of each alternative (Pearce & Robinson, 1995; Wortman, 1982). While executive values and personality can dispose decisions in particular directions (Child, 1972; Hambrick & Mason, 1994; Peterson, Smith, Martorana, & Owens, 2003), for the most part strategic decision making reflects a systemic, data-driven process and analysis. And, given their early career success and lofty position, it is likely a process at which most top executives excel (Sessa & Taylor, 2000a). However, when the time comes to make what is the most

important strategic decision for top executives (Lorsch & Khurana, 1999), they apply ad hoc, intuitive procedures that are not designed to produce the best outcomes. Also, the kinds of qualities that define exemplary leadership skills may not be easily accessed by the kinds of quantitative business data favored by top executives (Bennis & O’Toole, 2000). To reduce failure in executive hires, search teams need to employ more effectively the processes and tools associated with successful personnel selection. Effective selection actually reflects the integration of multiple processes ranging from the specification of position and applicant requirements to recruitment and screening of applicants to the selection of winning applicants and their eventual entry to their position (Dunnette, 1966; Guion, 1976; Wanous, 1992). Each component of personnel selection requires a set of orderly 7 procedures grounded in careful analysis and best practices. For executive selection, these

procedures take on added dimensions – the complex nature of the executive position, the difficulty in assessing “leadership qualities” (Bennis & O’Toole, 2000), and the collective nature of executive selection decisions introduce several layers of complexity to traditional selection practices. Also, changes in organizations and in their operating environments can drive changes in selection procedures (Cascio & Foglio, in press), especially at the executive level. Accordingly, given the importance of executives to organizational performance, special care needs to be devoted to the process and components of executive selection. The Components of Executive Selection The selection of top executives is at once both similar to and qualitatively different from more traditional personnel selection processes. The similarity resides in the procedures of defining job or position requirements, specifying candidate attributes, applying validated assessment procedures and making

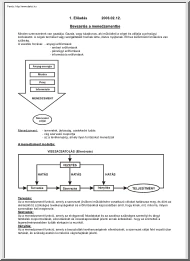

hiring decisions (Sessa, Kaiser, Taylor, and Campbell, 1998). The differences lie in the particular demands and challenges to these procedures posed by the unique nature of executive level leadership. For example, Hollenbeck (1994) noted that “selecting CEOs is unlike other selections in the organization: Different people are involved; there are many more variables, and they are more complex and constantly shifting; the process ordinarily takes place over a long time; and it will draw more attention than any other event in the organization” (p. 4) Thus, while the surface processes are the same as other forms of personnel selection, how these are implemented, the variables that define their success, and the best practices for each specific process are quite different. In this review, I focus primarily on five processes or components of executive talent assessment and acquisition – these are shown in Figure 1. These components reflect an 8 Definition of Position Requirements

Specifying what potential executives will likely need to accomplish in the short and long term in the targeted positions Delineation of Desired Candidate Attributes Specifying what would be the attributes and qualifications of the ideal candidate Recruitment of Potential Applicants Building a pool of applicants from within and/or outside of the organization Assessment and Evaluation of Candidates Determining the candidates’ standing on the targeted attributes defined in step 2 Selection of Desired Candidate Using decision processes and metrics to determine the best candidate for the targeted position Figure 1. Components of Executive Talent Assessment and Acquisition 9 integration, although with a slightly different emphasis, of those suggested by other researchers and practitioners (e.g, London & Sessa, 1999; Hoffman, Schniederjans, & Sebora, 2004; Parise, 2003; Sessa, et al., 1998; Sessa & Taylor, 2000a, 2000b) The first process refers to defining position

requirements. This process reflects the specification of what the potential executive needs to accomplish in the targeted position; it involves defining the expected performance imperatives for the executive. Zaccaro and Klimoksi (2001) described seven general imperatives for organizational executives: cognitive, social, personal, political, financial, technological, and staffing. These imperatives “[derive] from factors or forces that co-exist in the context or operating environment of a senior leader” (p. 26) Accordingly, executive selection procedures need to start with a careful consideration of what these imperatives are likely to be for incoming executives, and how they define future position requirements. After the specification of position requirements, the second execution processes refers to delineating desired candidate attributes. This delineation should follow from an understanding of how particular executive qualities will help the organization meet anticipated (and

unanticipated) strategic challenges. However, members of executive selection boards and staffing directors typically proceed by either looking for characteristics similar to their own (Zajac & Westphal, 1996), using ones from prior searches, or by relying on “gut instincts and intuition (Howard, Erker, & Bruce, 2007). The result is often the selection of executives that fit past performance models, or those that are mismatched to existing and emerging performance imperatives. Once desired executive attributes are defined, the third process, recruitment of candidates, begins. Candidates can come from inside and outside of the organization More research has perhaps been completed on this aspect of executive selection than most others. 10 However, conclusions about best practices on executive recruitment remain muddy. While the traditional recruitment literature stresses the superiority of candidates who are familiar with the organization (Wanous, 1992), most executive

search committees seem to prefer outside candidates, at least under several typical circumstances (Sessa et al., 1998) After a pool of candidates has accumulated, the assessment and evaluation of candidates occurs with the application of a range of assessment tools and procedures. This process is perhaps the other most researched component of executive selection. A variety of tools and tests have been suggested in the leadership literature (Howard, 2001, 2007; London, Smither, & Diamante, 2007). However, whether (a) the tools accurately assess the executive attributes they are intended to assess (i.e, construct validity), and whether (b) the tools sufficiently predict future success in executive positions (i.e, criterion-related validity) remain somewhat contentious issues in this literature. Further, a number of scholars have noted the tendency of executive selection committees to eschew these tools in favor of reliance on word-of-mouth references, and unstructured interviews that

loosely, if at all, reflect targeted attributes (DeVries, 1993). The data from candidate assessments are used in the fifth executive acquisition process, the actual selection of the desired candidate. An important consideration in this process is how the data are integrated and combined into a final choice. This decision typically involves multiple stakeholders, with several of them having different perspectives and agendas. Accordingly, each stakeholder can be disposed to a different candidate. Thus, the selection of a final choice for an executive position often reflects an intricate combination of assessment conclusions with strategic, political, and personal posturings of multiple decision constituencies. 11 Fully successful executive selection rests on the effective enactment of each and all of these processes. As various reviews of the executive talent acquisition literature (Cascio & Foglio, in press; DeVries, 1993; Hollenbeck, 1994; Howard, 2001; 2007; Sessa &

Taylor, 2000a) attest, however, a substantial gap exists between current and best practices in each of these five areas. The reminder of this paper summarizes research on these processes with the intent of identifying prescriptions for more effective executive selection. Definition of Position Requirements The starting point for executive selection is a process of stakeholders, especially the current top executives, selection committees, and boards of directors, developing a shared understanding of what organizational imperatives need to be addressed in filling a particular executive position (Sebora & Kesner, 1996; Sessa, et al., 1999) The following factors can determine executive performance requirements: • The fundamental or generic nature of all executive work; • Changing phases in the growth or progress of the hiring organization • Current contextual challenges facing the organization • The strategic direction of the organization intended by current top

executives and the board of directors (Sessa, et al., 1998) The reality of current executive selection is that few organizations conduct the kind of a priori comprehensive position analysis that includes all of these factors. In a study of over two dozen instances of forced CEO dismissals, RHR International (2002a) found that in many cases the company had not put sufficient time and resources to define what was to be required of a new CEO. Sessa and Taylor (2000a p 45) also observed that “today’s executives show little inclination to analyze organizational needs and position requirements before filing an open 12 executive position.” This lack of patience or attention to such an analysis becomes even more acute when an executive vacancy is a sudden or unanticipated one (Khurana, 2001). In these circumstances, Khurana (2001) notes that market and financial pressures outside of the company, and the uncertainty that grows within the company from a high level executive opening,

can create a significant press to fill a position as quickly as possible. The problem that results from an insufficient position analysis and specification of executive performance requirements is an increased probability of hiring the wrong executive, with greater turmoil down the road. Indeed, Sessa et al (1998; see also Sessa & Taylor, 2000a) found from interviews with 494 executives that those who reported successful executive selection outcomes in their company were more likely to engage in the processes of defining organizational needs, position requirements, and desired candidate attributes than those who reported unsuccessful outcomes. Thus, even in pressing circumstances, selection stakeholders need to complete an organizational and position analysis that reflects the four aforementioned factors. A better practice, however, is to attend to such factors on a continuing basis so that the organization is more prepared for any sudden executive vacancy. The Nature of Executive

Work Defining executive position requirements begins with an understanding of how executive leadership differs fundamentally from leadership at other organizational levels. Several models have carefully delineated qualitative shifts across levels of organizational leadership. For example, Katz and Kahn (1978) noted that at lower organizational levels, leaders are concerned with administering and managing within existing policies and structures. Their performance requirements consist largely of translating organizational goals provided by their superiors into more immediate (i.e, daily to a 1 year time frame) tasks, plans, and responsibilities (Jacobs & 13 Jacques, 1987). They also need to address the obstacles to progress at this level using existing organizational mechanism and contingencies (Zaccaro, 2001). At middle organizational levels, Katz and Kahn (1978) argued that leaders are required to extrapolate and put into operational terms new structures and policies derived by

top organizational leaders. Their time span of work stretches from 1-5 years (Jacobs & Jaques, 1987). Middle managers are also likely to be leading multiple organizational units, meaning they are now managing other lower-level managers (Bentz, 1987; Mumford, Zaccaro, Harding, Fleishman, & Reiter-Palmon, 1993). Accordingly, their performance requirements include operational planning, and the coordination and integration of actions across multiple functional units. At the executive level, leaders need to adopt a more long term (5-20 year), strategic perspective (Jacobs & Jaques, 1987). According to Katz and Kahn (1978), such a perspective means they are likely to mostly involved in originating policy and structure to be implemented across organizational systems. These leaders also spend more of their time as boundary spanners, representing their organizations to outside stakeholders and constituencies (Zaccaro, 2001). They also need to balance multiple leader roles more so

than at managers at lower organizational levels (e.g, mentor versus director, facilitator versus producer, innovator versus coordinator, broker versus monitor; Hooijberg , 1996; Hooijberg & Quinn, 1992; Quinn, 1984) Accordingly, their performance requirements entail long range strategic planning and implementation., boundary management, and providing vision and motivation to the entire organization (Zaccaro, 2001). Figure 2 summarizes the elements of executive work that are common across most organizations. These elements serve as the baseline for defining the position requirements of most executive jobs. 14 Empirical support for differences in position requirements across organizational levels has been provided by a number of researchers (Alexander, 1979; Mahoney, Jerdee, & Carroll, 1965; Page & Tornow, 1987; Paolillo, 1981; Pavett & Lau, 1982). Baehr (1992) examined job functions of 1358 managers and found different clusters of functions at each organizational

level. Lower level managers were primarily engaged in team-building, supervising, handling emergencies, and managing and developing personnel. Middle level managers focused mostly on coordinating interdepartmental activities, communicating, improving work practices, and engaging in more complex judgment and decision making. Executives were involved primarily in setting organization-wide objectives, communicating, promoting external relations, handling external contacts, and coordinating activities across multiple departments. Figure 2 Common Elements of Executive Work in Most Organizations Conducting long range strategic assessment and planning Communicating a vision or plan for organizational progress and growth Managing relationships with external stakeholders Implementing organization-wide structural and policy changes Fostering a climate the motivates high performance across the organization 15 The baseline elements of executive work become minimum

threshold for specifying what should be expected of prospective executives. Thus, executive position requirements should include the activities indicated in Figure 2. Indeed, similar kinds of requirements are reflected, for example, in the core qualification for senior government executives derived by the Office of Personnel Management (Jordan & Shraeder, 2003; Office of Personnel Management, 1998). These include leading change, leading people, driving for strategic results, working with financial and business information recourses, and building coalition and professional networks, and communicating with multiple constituencies. Likewise, from their experiences in assessing and developing executives, Development Dimensions International identified nine generic executive strategic role requirements – navigator, strategist, entrepreneur, mobilizer, talent advocate, captivator, global thinker, change driver, and enterprise guardian (Appelbaum & Paese, 2003). Success in defining

executive position requirements means that at a minimal level the executive search team needs to consider these responsibilities of executive leaders. However, these qualities of executive work are still insufficient for fully describing what a company may require in a particular CEO or executive position. Most executive selection boards and committees likely take most of these requirements for granted. Achieving a better fit between eventual hires and position requirements requires an analysis of the environmental pressures, challenge and internal dynamics that are unique to the hiring organization (Sessa, et al., 1998) Organizational Cycles One of the most important of these challenges reflects where the organization is in its growth or change cycle. Organizations that are concerned with maintaining the status quo in terms of their strategic position will need one type of executive. Others that focus on rapid 16 growth, or turning around a poor-performing company, will have

different performance requirements for potential executives. Accordingly, in their interviews with 494 top executives, Sessa et al., (1998) found that executives considered needs such as “sustain the organization,” “developmental position,” “growth of the organization,” “turn around,” “start-up,” “cultural/structural change,” and “restructuring” as important to take into account in their definition of executive job requirements. Several of these factors reflect the prior and continuing performance level of the firm. For example, in companies that have been experiencing lower performance and profitability (i.e, presenting a “turn around” circumstance to an incoming CEO), executive selection committees may conclude that innovative strategic thinking is crucial in a new executive; accordingly, they are more likely to seek and select an outside candidate with fresh ideas, or an inside executive who has not been with the company too long (Barker, Patterson,

& Mueller, 2001; Datta & Guthrie, 1994; Guthrie & Datta, 1997). Alternatively, when firms are doing well, and therefore wish to maintain current strengths and their existing strategic focus (i.e, a “sustain the organization” circumstance), executive selection committees may place more importance on potential new executives having high familiarity with company structure, operations, and plans; they may also place a greater emphasis on strategic implementation than strategic innovation. Accordingly, “heir apparents” to the existing CEO (ie, “relay successions;” Vancil, 1987) may be more favored – indeed, Zhang and Rajagopalan (2004) found significant support for just such relationships between firm prior performance and incidents of relay successions. Along these lines, Ocasio and Kim (1999) found that companies with a recent history of frequent mergers and divestures (i.e, “restructuring” or “strategic change” circumstances) were less likely to seek new

executives from production or marketing backgrounds relative to 17 backgrounds in finance and operations. Likewise, if organizations were experiencing lower performance levels, then their executive selection committees were more likely to be searching for executives with operations background. Other studies have shown that firm size influences selection decisions, such that smaller companies are more likely to choose outside candidates (Lauterbach, Vu, & Weisber, 1999; Guthrie & Datta, 1997). Smaller companies are more likely to be concerned with expansion (i.e, “growth” circumstances) and therefore may be looking for different types of human capital than exists among their current group of executives (Giambatista, Rowe, & Rias, 2005). These studies point to the importance of internal organizational characteristics relative to strategic goals in determining requirements for new executive positions. Accordingly, needs assessments conducted at the beginning of the

executive selection process should focus on such characteristics as the hiring organization’s size, structure, climate, values, needs, strategic goals, prior performance trajectories and financial positions (Sessa et al., 1998) Contextual Challenges The aforementioned factors are internal to the organization. External or contextual contingencies also influence the work that is likely to be required of newly selected executives (Sessa, et al., 1998) For example, high strategic variance or instability in a hiring organization’s industry sector coupled with high dynamism in the strategic environment increases the need for new executives to display greater strategic flexibility and adaptability (Kwaitkowski, 2003). Executives may have to engage in more environmental scanning and networking in such environments. These kinds of work imperatives increase the likelihood of needing executives who have fresh perspectives and very large professional networks, with experiences in multiple

contexts. Such executives are more likely to come from outside of firm and even outside of the 18 industry. Indeed, Zhang and Rajagoplan (2003) found that when firms were located in industry sectors with strong strategic homogeneity or when such firms possessed strategic goals that conformed to the industry central tendencies, new executives were more likely to come from intraindustry origins. Accordingly, the obverse of this finding would suggest that greater strategic heterogeneity would increase the premium on strategic innovation and adaptability, and therefore favor executive candidates from outside the firm’s industry sector. The global strategic positioning of an organization also poses contextual influences that influence executive work. Today’s executives are working increasingly across international and multicultural boundaries (Ireland & Hitt, 1999; Suutari, 2002). Accordingly, London and Sessa (1999) argued that the organizational needs assessment and

specifications of executive work requirements should consider potential global demands on the executives to be hired. They argued that companies can operate at three levels of globalization (see also Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989) – (a) dealing with constituencies and stakeholders from different cultures but from a strong or dominant corporate base within one culture; units in other cultures are directed from the perspective of the corporation’s home culture (b) developing connections among decentralized corporate units, each reflecting local cultures and business customs; (c) developing a transnational culture within the corporation that integrates and supersedes local cultures. These levels reflect increasing global complexity within the organization. Likewise, London and Sessa argued that greater cultural complexity and diversity raises the cultural demands for top executives. Cultural complexity and demands contribute greater cognitive and social executive work requirements

(e.g, multicultural understanding; cultural intelligence; Earley & Ang, 2003) for such executives, and accordingly deserve unique consideration in the specification of their position requirements. 19 Organizational Strategy The analysis of both internal and external influences on executive performance requirements alludes to the importance of organizational strategy. Indeed, many scholars and experts in executive selection argue for the primacy of strategy in defining such requirements (Gupta, 1984, 1986, 1992; Guthrie & Datta, 1997; 1998). RHR International (1998) asserted that “[succession planning] is about creating a fit between what the company must do strategically and the person who can best implement that strategy” (www.rhrinternationalcom/files/EI/155htm) Sessa et al (1998) noted from their interviews with 494 executives who had engaged in CEO and top executive selection that strategy was the top factor in defining position requirements. This focus fits with

the increasing emphasis on strategic staffing in the selection literature (Bechet, 2008; Gupta, 1992; Snow & Snell, 1993). Snow and Snell argued for three different models of staffing. One reflects the traditional selection approach which seeks to match the person with relatively stable job or position requirements (e.g, job-driven competency modeling; Howard, 2001). Sessa et al noted that such approaches are characteristic of leader selection processes at lower organizational levels where they are “geared toward hiring employees whose knowledge, skills, abilities, and characteristics provide the greatest fit with requirements of specific jobs, without taking the organizational needs into account (p. 5) Snow and Snell’s (1993) two other models emphasize strategy as a critical driver of strategy. One approach specifies staffing and selection as a reaction to intended strategy Thus, executive selection becomes part of the process of strategic implementation. Such an approach

should fit organizations with mostly set strategies operating in relatively stable contexts. Most executive selection committees that use existing or emergent strategy to define position 20 requirements adopt this perspective. Howard (2001) labels this approach as strategy-driven competency modeling, where position requirements (and therefore position competencies) reflected organizational life cycles, broad role expectations, or the company’s’ cultural values. Summers (1997) describes the steps in completing a strategic skills analysis that helps define position requirements as a function of anticipated long range changes in targeted jobs. These and similar approaches help guide HR talent acquisition processes in tandem with established or anticipated organizational strategies. Alternatively, in line with Snow and Snell’s third model, some circumstances call for staffing or selection as part of a strategic formation process, in which executives are hired based on

expectations that they will develop appropriate strategies for the company based on what may be rapidly shifting environmental contingencies. Such executive selection can be the most complex as selection committees do not operate from a firm strategic frame of reference regarding where the potential executive might take the company. Instead, they would focus on a candidate CEO’s strengths in developing what could be at the time a mostly unknown strategy for the company. Summary I began this section with the observation that while defining what will be expected of new executives is an important first step in executive selection, few companies conduct the kinds of analyses necessary to uncover these expectations. I have suggested that several elements influence executive work expectations, and a good executive position analysis should focus on all of these. Figure 3 reflects these elements The position analysis begins with agreement on the typical elements of executive work – most

companies assume such elements (see Figure 2). These common elements, however, become filtered through considerations of where the organization is in its growth phase, what current challenges exist in the organization’s operating 21 environment, and what strategic goals have been adopted by the organization. These considerations inform the final definition of executive performance requirements. When the analyses suggested by the elements in Figure 3 are conducted properly, they provide a road map for the rest of the selection process. Position requirements serve as the basis for defining requisite executive competencies, which in turn suggest the assessment strategies that are best able to uncover them. The data from these assessments provide the basis for subsequent hiring decisions. Thus, if executive selection stakeholders fail to derive and agreed on a shared understanding of executive position requirements, the result will likely mean a derailed effort in the subsequent

steps of the executive hiring process. Delineation of Requisite Executive Attributes Categories of Executive Attributes The premise that the nature of leadership varies across organizational levels means that unique attributes define success at the executive level versus at lower leadership levels. Katz (1955) identified three sets of managerial skills: technical, human (interpersonal) and conceptual. He argued that relative to one another, technical skills was of highest importance to managerial effectiveness at the lowest level of organizations, interpersonal skills were constant in importance across levels, and conceptual skills were highest in importance at the executive level. While agreeing that technical skills decrease and conceptual skills increase in importance at higher organizational levels, Zaccaro (2001) argued that increases in social complexity at executive ranks means that interpersonal skills also become more important at this level, an assertion echoed by others

(Bennis & O’Toole, 2000; Hooijberg, Hunt, & Dodge, 1997; Sessa & Taylor, 2000a). 22 Common Elements of Executive Work Phase in Organizational Growth Current Contextual Challenges Anticipated Organizational Strategy Expected Executive Performance Requirements Figure 3. Influences on the Definition of Performance Requirements for New Executives A recent empirical investigation by Mumford, Campion, and Morgeson (2007) described somewhat different and more precise categories of these skills and examined how they changed across levels. Cognitive skills referred to basic information utilization and problem solving skills, critical thinking skills, and skills in communication and reading comprehension. Interpersonal skills referred to social awareness and judgment skills, persuasion and negotiation skills, and skills in coordinating others. Business skills referred to business acumen and skills in managing financial, material, and personnel resources. Finally

strategic skills refer to skills in 23 systems-level perceptiveness and understanding, visioning, complex problem solving, and to skill in developing complex cognitive representations of strategic environments. Mumford et al asked 1023 managers at three organizational levels to rate the importance of each set of skills for work at their level. They found that strategic and business skills demonstrated the sharpest increases by organizational level, followed by interpersonal and cognitive skills, respectively. Thus, at the executive ranks, while basic cognitive and interpersonal skills continue to contribute to overall success, business acumen and strategic skills become proportionally more important. Changes in Desired Executive Attributes A number of other researchers have described the executive competencies and attributes that guide many executive searches. Comparisons of the most recent lists with those from about 10 years ago indicate some interesting changes. For example,

Sessa et al (1999) noted from their interviews with hundreds of top executives attending programs at the Center for Creative Leadership that at that time the top five requirements sought in executive candidates were, in order, specific functional background, managerial skills, interpersonal skills, communication skills, and technical knowledge. The bottom five were flexible/adaptable, creative/innovative/ original, intelligent/fast learner, fits with culture, and strategic planning skills. In 2007, based on a survey of over 1100 managers about what leadership skills would be important over the next five years the Center for Creative Leadership found that the following were top leadership skills: collaboration, change leadership, building effective teams, influence without authority, and driving innovation (Martin, 2007). Adaptability, which was at the bottom of Sessa et al’s list, was 8th on the 2007 list. A similar survey of 412 executives conducted for Development Dimensions

International (2008) found that top leadership qualities anticipated over the next five years were the abilities to motivate a team, work across cultures, facilitate change, develop 24 talent and make tough decisions. Technical expertise, interpersonal skills, and an ability to “bring in the numbers” were at the bottom of the list, the opposite of what Sessa, et al reported 10 years earlier. These surveys over a 10-year span suggest a significant shift in the kinds of attributes considered most important in future executives. These attributes emphasize more skills in managing in a dynamic, fast-paced environment that extends across national boundaries. They also indicate more complex social capacities as emerging key attributes. Sessa and Taylor (2000a) referred to similar kinds of capacities as reflecting the ability to develop and maintain high quality relationships across organizational stakeholders. These relationships become crucial for such tasks as motivating systems,

building effective teams and multi-level collaborative relationships. Sessa and Taylor argued that relationship skills differ from interpersonal skills in that the latter can produce more superficial and broader personal connections; relationship skills result in deeper and longer-lasting connections. Deeper connections are more important for fostering the kinds of organization-wide support needed in a fast paced and changing environment – subordinates are more likely to follow your lead in such circumstances when the connection between you and them is a close one. Indeed, Sessa and Taylor found in their research that it was relationship skills, rather than performance skills, that distinguished successful from unsuccessful executives. Bennis and O’Toole (2000, p 172) described similar sets of skills as “the ability to move the human heart.” Sessa and Taylor also point to the difficultly in assessing such skills, noting that, while interpersonal skills will likely produce

effective interviews in executive selection contexts, relationships skills “are harder to judge at first glance and during superficial meetings (for example, interviews) with executives” (p. 24) 25 Research on executive performance requirements has also emphasized the need for executives to balance multiple roles as part of their responsibilities (Hooijberg & Quinn, 1992; Quinn, 1984). Hooijberg and Schneider (2001) labeled the ability to accomplish such balance, behavioral complexity, and described it as an important executive skill. This skill, according to Hooijberg and Schneider, has two components, behavioral repertoire and behavioral differentiation. Behavioral repertoire refers to “portfolio of leadership roles a leader can perform (p. 108) Several studies have shown that executives with a wide repertoire are more effective as leaders than executives with more narrow repertoires (Denison, Hooijberg, & Quinn, 1995; Quinn, Spreitzer, & Hart, 1992). Their

companies also exhibit higher performance (Hart & Quinn, 1993). According to Hooijberg and Schneider, behavioral differentiation refers to the leader’s ability to perform roles in their repertoire differently depending upon organizational circumstances. This skill is similar to the components of social intelligence that reflect behavioral flexibilitiy (Zaccaro, Gilbert, Thor, & Mumford, 1991). In addition, Kaplan and Kaiser (2003) describe the related skill of versatile leadership, or the ability to balance strengths in forceful versus enabling leadership and strategic versus operational leadership. These skills have also been linked to executive effectiveness (Hooijberg & Schneider, 2001: Kaplan & Kaiser, 2003). Boal and Hoojiberg (2000) extended these ideas by arguing that such attributes as behavioral complexity and social intelligence contribute to three central executive skills – absorptive capacity, capacity to change, and managerial wisdom. Absorptive

capacity refers to “the capacity to recognize new information, assimilate it, and apply it toward new ends (p. 517) Managerial wisdom, according to Boal and Hooijberg, reflects abilities to perceive and 26 understand variation in the environment and in social relationships, as well as the “capacity to take the right action at a critical moment” (p. 518) These factors, along with the capacity to change, define executive effectiveness within the strategic dynamism that characterizes today’s operating environment for most organizations (Ireland & Hitt, 1999). Accordingly, they need to be considered more centrally in today’s executive searches. The ability to learn, which represents a key component of the executive skill set defined by Boal and Hooijberg (2000), would likely become most important in executive staffing models that seek candidates who would be tasked with forming new strategies (i.e, Snow and Snell’s third model), rather than implementing existing

strategies. Spreitzer, McCall, and Mahoney 1997) argued that while most executive searches rely on the kinds of “end-state competencies” summarized by many treatments of executive leadership (e.g, see Zaccaro, 2001 for a review of such competencies), the “ability to learn from experience” should demonstrate added value in predicting success by international executives. They argued that if executive searches limited their desired candidate attributes to end state competencies, they “risk choosing people who fit today’s model of executive success rather than the unknown model of tomorrow” (p. 6) However, if such competencies were complemented with high levels of learning-oriented attributes (e.g, cross-culturally adventurous, seeks opportunities to learn, seeks feedback, is flexible), in other words with absorptive and adaptive capacity, then such searches are more likely to select candidates who could be effective in dynamic and uncertain environments. In support of this

argument, Spreitzer et al. developed an instrument to assess both end-state competencies and the ability to learn from experience (Prospector – see below), and examined its associations with supervisor ratings of a manager’s executive potential; they reported that several end state competencies and attributes related to one’s ability to learn differentiated 27 between “managers with high potential and those who were solid performers but not likely to advance” (Spreitzer, et. al, 1997, p 19)) The Attributes of the Global Executive Part of the genesis of Spreitzer et al’s (1997) work was to examine predictors of international executive potential. Indeed, they found that several of the end state and ability-tolearn competencies significantly predicted supervisor ratings of a manager’s ability to deal with international issues. Due to the increasingly globality of executive work, attributes that reflect cross-cultural skills are becoming more prominent qualifiers in

executive searches. Development Dimensions International’s recent survey of 412 executives indicated that “works well across cultures” was rated as the second most important leadership quality for the next 5 years (DDI, 2008). In reviewing research on selecting international executives, London and Sessa (1999) emphasized intercultural sensitivity as a key executive competency. They defined this sensitivity has having nine dimensions (p. 10) – “(1) comfort with other cultures, (2) positively evaluating other cultures, (3) understanding cultural differences, (4) degree of empathy for people in other cultures, (5) valuing cultural differences, (6) open-mindedness, (7) sharing cultural differences with others, (8) degree to within feedback is sought about how one is received in other cultures, and (9) level of adaptability.” Research by Earley and Ang (2003) extends this notion into the broader concept of cultural intelligence. These contributions suggest that closer and more

systematic attention needs to be paid to global leadership attributes in defining candidate attributes in the executive search process. Unfortunately, executive searches for global assignments are usually conducted under strong time constraints, with a primary focus on internal candidates who have demonstrated success in 28 cultural projects while at their base in their home country – little consideration is given to their skill in managing within foreign cultures (Black, Greghersen, Mendenhall, and Stroh, 1999). Indeed, Hurn (2006) noted that “it is still rare for companies to judge their potential managers’ ability to be effective overseas against any clearly-defined criteria” (p. 281) For executive talent acquisition to be more successful in the future, search and selection committees will have to become more cognizant of such abilities and factor them into their assessment and decisions making processes. Summary This section described a number of specific points about

the attributes executive selection committees could target in their search. First, four categories of attributes have been identified as important for organizational leadership. These are shown in Figure 4 Second, while many attributes are important for effective leadership, at the executive level, business acumen and strategic skills become proportionately more important. Third, what are considered to be crucial executive attributes have changed over the last decade. Today, companies are citing adaptability, cross-cultural and global management skills, talent development skills, team and relationship building, and capacity to change as desired attributes for future executives. Accordingly, these kinds of qualities need to drive the assessment of executive candidates. That is, the measures used to examine candidates need to target these attributes. However, as shown in a later section of this report, most assessment tools fail to focus specifically on these attributes. 29 Social

Attributes Cognitive Attributes Intelligence Basic Problem Solving Skills Critical Thinking skills Creative Thinking skills Ability to Learn Absorptive capacity Business Attributes Business Acumen Finance management skills Organization management skills Global networking skills Communication skills Social awareness skills Social judgment skills Persuasion and negotiation skills Collaboration skills Team building skills Relationship building skills Behavioral complexity Multicultural awareness and sensitivity Strategic Attributes Systems level awareness skills Visioning skills Complex problem solving skills Ability to map operating environment Organizational change skills Innovation skills Adaptability Talent management skills Figure 4. Categories of Executive Attributes (Note: Category labels were adapted from Mumford, et al., 2007) 30 Recruitment of Position

Candidates The specification of candidate attributes triggers the next processes in executive selection – the recruitment of potential candidates and the use of assessment procedures to gather information about candidates. This section focuses on recruitment while the next examines assessment practices. Preferences for Internal versus External Candidates Research and practice on executive recruitment has centered primarily on the circumstances, advantages/disadvantages, and consequences of seeking candidates from within or outside of the organization. A number of studies and reviews indicate that most companies generally look outside of the firm to fill around 20-40% of executive vacancies (Byham, 2003; RHR International, 2005; references), although this number can be as high as 70 to 93% in companies from the private nonprofit sector, or in small (< 1000 employees) companies (Sessa et al., 1998) Internal successions can be divided in those in which there was or was not an “heir

apparent” A succession from a CEO to an obvious heir apparent is called a “relay succession” (Vancil, 1987; Zhang & Rajagopalan, 2004). External successions can also be divided into those in which the new CEO origins reside inside versus outside the hiring firm’s industry (e.g, Zhang & Rajagopalan, 2003). Research has uncovered several reasons for selecting internal versus external candidates (Giambatista, Rowe, & Riaz, 2005). These reasons include: • High firm performance prior to executive hiring: When companies are doing well and an executive position opens, selection committees are likely to be less willing to risk any significant changes that might result from hiring an external candidate. Lower firm performance suggests a stronger need for significant shake-up and favors an external 31 candidate. Accordingly, Datta and Guthrie (1994) found that when organizations evidenced lower profitability and growth prior to an executive opening, they were more

likely to hire external CEOs, a finding also reported Lauterbach, et al. (1999) Zhang and Rajagopalan (2004) also found that heir apparent candidates were more likely to be selected when prior firm performance was high. • Number of strong internal candidates: A large number of internal candidates, particular those who also serve on the board of directors (e.g, executive vice presidents) suggest that the organization has a deep bench and perhaps a strong senior management development program. Both conditions should increase the probability of hiring internal candidates Zhang and Rajagopalan (2003) reported support for this premise in their study of 220 CEO successions. • Number of non-CEO inside directors and stockholders: When inside executives have considerable power over organizational decisions by virtue of serving on boards of directors or having significant stock ownership, they are in a stronger position to challenge current CEOs and position themselves or other internal

candidates as successors. Along this line, Shen and Cannella (2002a) found that higher numbers of both non-CEO board members and non-CEO executive ownership was more likely to result in CEO dismissals followed by an internal succession. • Firm size: A smaller firm is less likely to have a large number of qualified candidates and therefore is more likely to look for an external candidate. Studies by Sessa et al, (1998), Lauterbach, et al (1999) and Barker et al. (2001) provide empirical support for this argument 32 Source of Recruitment and Subsequent Organizational Performance The decision of an executive selection committee about where to look for executive candidates is premised presumably on the belief by the selectors that the origin of a particular chosen executive will improve the firm’s performance, particularly when choosing an external candidate. But research on this question suggests at best a mixed picture, and more often the result of hiring externally is often

lower performance. Sessa et al (1998) noted that executives were more likely to prefer recruiting external candidates (57%) versus internal candidates; however, internal candidates were consistently reported by the executives in their sample as having subsequently higher success rates in their new positions than external candidates, even when the reasons for succession seemed to favor external candidates. For example, in companies dealing with a start up circumstance, internal candidates were still more successful than external candidate. This same finding occurred for those companies charting new directions, dealing with cultural or strategic change, or when they needed to develop their people – all circumstances which have been suggested as favoring external hires (Howard, 2001). Shen and Cannella (2002b) found in a study of 228 succession events in publicly traded corporations, that outsider succession resulted in lower post-succession performance; this effect was even worse when

such succession was accompanied by high levels of executive turnover. Zhang and Rajagolpalan (2004) found that internal successions in 200 firms, particularly relay successions, were associated with higher subsequent performance. A study by Booz Allen Hamilton found that while the numbers of external hires increased significantly between 1995 and 2003, “55% of outsider CEOs in North America, and 70% of outsider CEOs in Europe were forced to resign for performance related reasons in 2003” (Karaevli, 2007, p. 682, citing Lucier, Schuyt, & Handa, 2003). Finally, Collins’s (2001) study of 11 companies who exhibited 15 33 years of below average growth (for their business sector) followed by 15 years of above average growth found that of 42 CEOs across these “good-to-great” companies, only 2 (about 5%) were outsiders. Of the companies that were direct comparisons to these in terms of firm characteristics and opportunities, but did not grow at similar rates to similar

levels, 20 of 65 CEOs (about 31%) were outsiders. Countering these findings, though, a recent study by Karaevli (2007) articulated some circumstances in which external executive successions resulted in better performance; outside CEOs were more likely to result in higher post-succession performance when (a) the firms operated in environments that were more conducive to organizational growth, (b) pre-succession performance was particularly low, (c) strategic changes were not made swiftly, or when (d) outside CEOs were accompanied by large changes in the executive team. Reviews of the executive succession literature have argued that organizations should recruit from both external and internal sources (e.g, Howard, 2001) However, based on the findings summarized here, as well as on other similar data, Byham (2003; Byham & Benthal, 2000) has argued that companies should look more to internal candidates in hiring executives, and put more investments in building their pool of internal

candidates. This means focusing more on leader development and succession management programs. While companies have begun to increase their leadership investment, the trend is still very recent – RHR International (2005) found that 88% of the companies they surveyed had been formally engaged in the development of future leaders for only a period of 3 years or less. This review is not intended to argue for exclusively internal succession. Karaevli (2007) noted instances where external CEO successions improved firm performance. Even when making “the case of internal promotions” Byham and Bernthal (2000) asserted that “there might 34 be times that external candidates would be more appropriate for filling open positions. For example, rapid expansion, the need for fresh perspectives, and the acquisition of new skill set can all be addressed by external hiring decisions?” (p. 2) Howard (2001) also agrees that firms in trouble may benefit from external successors. However,

recruitment of external candidates needs to improve in order to reduce the likelihood of subsequent failure. Sessa and Taylor (2000a) argued that different sources and kinds of information are available for external versus internal candidates, such that external candidates usually yield proportionately more positive information, while internal candidates provide data that is more balanced between positive and negative information. Zhang (2008) studied early dismissals of newly appointed CEOs, arguing that the information asymmetry existing between internal and external CEOs, (where boards have more information on internal CEOs) causes boards to make worse decisions about external CEO candidates. She found that indeed across 204 CEO successions in 184 firms, external candidates were much more likely to be dismissed after a short time than internal CEOs. This asymmetry of data about internal versus external candidates comes in part from the sources of recruitment for each type of

candidate. Howard (2001) summarized several studies that show external candidates are being recruited by executive search firms using strategies such as cold calls, publicly available directories, old contacts, and web-based searches. Many companies are advertising for executives directly on the Internet (Barner, 2000). However, research on recruitment sources for most job openings suggests that these external sources for potential applicants are demonstrably inferior to the kinds of sources that attract candidates with higher knowledge about the hiring company (Zottoli & Wanous, 2000). In a summary of this research, Zottoli and Wanous found that internal sources such as in-house postings, referrals by employees, and rehiring of former employees resulted in less turnover and higher performance 35 by the eventually hired candidates than external sources such as employment agencies, advertisements, job fairs and campus visitations. While few studies have specifically extended

this research to executive recruitment, the research cited earlier on the general superiority in performance from internal CEO successors and the quicker forced dismissals of external CEOs suggest that the differences in source yields found in studies of general job recruitment may extend to executive recruitment. Summary Figure 5 provides a summary of the circumstances that lead companies to favor recruitment of executive position candidates from inside versus outside of the organization. In essence, when companies are doing well, do not want to make significant strategic shifts and/or have a deep bench of strong executive candidates, they are more likely to favor internal candidates. When companies are not doing well, do not have bench strength, and/or feel the need to change their strategic focus, they are more likely to pursue candidates outside of the company. Research on executive performance after succession suggests that companies may ne favoring external succession more than

is warranted by the data – executives promoted from within the company tend to show better subsequent performance than those executives hired from outside. These findings point to the importance of companies implementing a strong executive succession program (Byham, 2003; Byham & Benthal, 2000). Studies by researcher and practitioners in the field of executive development and selection suggest the following best practices in executive succession management (readers are referred to the following sources for additional details: Byham, Concelman, Consentino, & Wellins, 2007; Lockwood, 2006; 36 Circumstances that Lead Executive Selection Committees to favor Internal Candidates Circumstances that Lead Executive Selection Committees to favor External Candidates High organizational performance before succession Number of inside executives on board of directors Strong executive and leadership succession program in place Larger companies Desire to maintain

current strategic direction Low or stagnant profitability and organizational performance before succession Weak bench; lack of a systematic leader succession program Rapid organizational growth Small firms Need for new strategic perspectives and skill sets Desire to chart a new direction Figure 5. Circumstances that Lead Executive Selection Committees to favor Internal or External Candidates Markos, 2002; McCall, 1998; McCauley & Van Velsor, 2004; Giber, Carter, & Goldsmith, 2000; RHR International, 2005; Smilansky, 2006; Weik, 2005; Wellins, Smith, Paese, & Erker, 2006): Have senior and top company executives demonstrate a strong commitment to executive succession planning and development, as noted in high percentages of dedicated resources and budgets Focus on the strategic goals of the company and on key “business drivers,” defined as “those priorities that leaders must focus on in order to successfully integrate the strategic and

cultural priorities of their organization (Byham, et. al, 2007, p 4) 37 Use strong assessment practices to (a) provide early identification of best candidates for executive development, (b) measure leadership progress through the program, and (c) index gains at program completion Use executive coaches and mentors as learning partners in executive development Make use of job rotation and developmental or “stretch” assignments for high potential managers Build accountability for developing potential executives in to succession management system Integrate executive development and internal succession planning into other human resource management systems Assessment and Evaluation of Executive Candidates Once a pool of candidates has been gathered, executive selection committees have the task of gathering information and evaluating each of the candidates. There exists in the academic and popular domains a large number of assessment tools for use in executive

selection. These range from assessments of cognitive skills and other psychological variables, to work samples and assessment centers, to interviewing. The quality and utility of these tests rests on ultimately on two basic validity questions – (1) do they accurately measure the executive attributes they are intended to measure, and (2) do they successfully predict who will mostly likely succeed in the executive position being filled. The first question reflects content validity; the second reflects predictive or criterion-related validity (Messick, 1995). The types of available tests cover a wide spectrum. Howard (2007) placed leader selection tests on a continuum ranging from those that provide inferences about likely leadership behavior, to those that ask for descriptions of past behaviors, to those that seek demonstrations of leadership skills. 38 Tests that provide inferences of behavior include cognitive ability tests, personality inventories, and leadership potential

inventories. Leader behavior descriptions include resumes, biographical data, and career achievement records. Assessment centers and work simulations represent examples of leader behavior demonstration strategies. Each of these strategies has its own strengths and weaknesses – the most appropriate assessment strategy is to use a combination of methods designed to minimize the weaknesses of each (Howard, 2007). Unfortunately, most executive selection committees rely too heavily on a few methods, usually interviews and records of past performance (Fernandez-Araoz, 1999; Sessa, et al., 1998) Indeed, for the most part, by their actions such committees have ignored general findings in research on assessment for selection purposes. For example, in their interviews with executives, Sessa et al (1998) found that 87% of them mentioned using interviews to select executives, followed by resumes (73%), and references (69%). Only 36% reported using tests and other instruments. However, research

has shown that the validity of interviews to predict executive success can vary widely depending upon several factors including whether the interview protocol is structured or unstructured, interviewers are trained or untrained, or the interview focuses on situational, job-related, or psychological content (McDaniel, Whetzel, Schmidt, & Mauer, 1994). Executive search committees typically use forms of interviews that tend to yield lower validities (Ryan & Tippins, 2004). Regarding other common candidate evaluation tools, Howard (2001) noted that (a) resumes can be untrustworthy as assessment tools because of inflation, and (b) references provide limited valuable information, and indeed often misleading information as former employees “praise generously and criticize sparingly”(p. 326), especially to avoid legal repercussions Thus the three top methods identified by Sessa et al. for measuring executives often end up being the most unreliable as sources of 39 information.

This observation adds weight to the recommendation that executive search committees use multiple assessment strategies, including those that provide inferences about behavior, past performance records, and demonstrations of behavior. Further, the gathering and evaluation of data should be accomplished by multiple assessors and raters. The result is often more reliable judgments (McDaniel et al., (1994) The disadvantage of using multiple methods and strategies is the higher cost (in time and money) of the executive selection process; but such costs need to be balanced against the costs of a failed executive (Cascio, 1994). The value of using combing assessment strategies lies in raising overall accuracy (Howard, 2007). I will briefly cover each of the prominent assessment strategies use in executive selection, with a summary of their strengths and limitations. Readers are referred to the various sources and citations for more details. Psychological Inventories and Cognitive Tests

Administering measures of psychological attributes to job candidates has been a staple of personnel selection for over a century (Landy, Shanmkster, & Kohler, 1994; Vinchur, 2007). Indeed, the first large scale use of cognitive tests in selection was intended for the purpose of identifying officer (i.e, leadership) potential in World War I (Salas, DeRouin, & Gade, 2007) In this brief review, I cover assessments of cognitive ability, personality, integrity, and leadership potential. Cognitive ability tests. Intelligence and cognitive capacity has been strongly linked to effective leadership (Keeney & Marchioro, 1998; Lord, De Vader, & Alliger, 1986). Models of multilevel organizational leadership argue that such capacities become more important as predictors of effectiveness at higher leadership ranks (Jacobs & Jaques, 1987; Zaccaro, 2001. Some cognitive ability and critical thinking tests widely used in personnel and leader assessment 40 include the Wonderlic

(Wonderlic, 1984), the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Wechsler, 1997), and the Watson-Glaser Critical Appraisal (Watson & Glaser, 1994). Such tests have demonstrated some of the highest validities among various personnel assessment procedures for predicting job performance (Bertua, Anderson, & Salgado, 2005; Ryan & Tippins, 2004; Schmidt, 2002; Schmidt & Hunter, 1998; Salgado, Anderson, Moscoso, Bertua, and Fruyt, 2003). Further, their validity for predicting complex jobs with higher cognitive loads, such as leadership, is stronger than for less cognitively demanding jobs (Howard, 2001 2007). Cognitive tests do pose two significant limitations for their use in executive selection. First, they are prone to adverse impact and therefore to legal challenge (Howard, 2007). Adverse impact occurs when different demographic groups yield significantly different average scores on a selection test, resulting in significantly different hiring percentages and rates (Hough,

Oswald & Ployhart, 2001; Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures, 1978). Hough et al (2001) found such impact due to age and ethnic/cultural difference s on general cognitive ability tests. Research also suggests that this potential limitation of cognitive ability tests for selection may not be easily overcome by combining them with other selection strategies (Howard, 2007; Sackett & Ellington, 1997). A second limitation is the likelihood of range restriction in general mental ability in candidate pools for high executive positions – most candidates at the executive ranks are likely to have high and comparable levels of intelligence (Howard, 2007). Tests of higher order cognitive skills, such as conceptual capacity (Jacobs & Jaques, 1987; Jacobs & McGee, 2001), or the ability to build complex cognitive maps or frames of reference, which may show greater discrimination among executives, may prove to more promising. One such measure, the Career Path

Appreciate technique, which is an assessment procedure combining tests with extended 41 interview, was given by Stamp (1988) to managers and used to predict their eventual attained organizational rank – predictive validities ranged from .70-92 Within the last 15 years, proponents have argued for more specific or specialized forms of intelligence as particularly important for executive work. One such form, emotional intelligence, has gained high visibility on the popular management literature (Caruso & Salovey, 2004; Goleman, 1995). Emotionally intelligent managers are better able to identify and understand their own and others’ emotional cues; they can also use and manage emotion effectively as they lead in the workplace (Caruso, Mayer, & Salovey, 2002; Caruso & Salovey, 2004). Work completed by the Center for Creative Leadership has shown how the failure to recognize and manage emotions in the work place can effectively derail the career trajectory of rising

executives (McCall & Lombardo, 1983). According to McEnrue and Groves (2006), the most prominent measures of emotional intelligence include the Emotional Competency Index (ECI-2; Sala, 2002), the Enotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-I; Bar-On, 1997), the Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (EIQ; Dulewicz & Higgs, 1999), and the Meyer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT;Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2002, 2003). They reported that all four measures exhibit moderate levels of validity in predicting performance, although the number of predictive studies is limited. Also, McEnrue and Groves concluded that the MSCEIT has moderate levels of content validity and high levels of construct validity; the other three measures were described as low on both forms of such validity with the exception of the EIQ, which exhibited moderate validity levels. The MSCEIT was summarized as being lower than the other tests on face validity. Regarding measures of emotional intelligence, Van

Rooy and Viswesvaran (2004) reported predictive validities of only about .23 with various measures of performance These 42 and other examinations of psychometric quality of emotional intelligence tests lead Sackett and Lievens (2008) to conclude that “we are still far from being at the point of rendering a decision as to the incremental validity of EI for selection purposes” (p. 428) Personality. Research on leadership and personality has focused primarily on the “Big Five” constructs, or the five factor model (FFM) – openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Hogan and Kaiser (2008) asserted that “personality drives leadership style – that who you are determines how you lead”, and argued that ignoring personality in the selection of senior executives would be “foolhardy” (p. 24) Judge, Bono, Ilies, and Gerhardt (2002) determined from a meta-analysis that all of the Big 5 traits except

agreeableness were significantly associated with leader effectiveness. Schmidt and Hunter (1998) reported a validity coefficient of .31 for conscientiousness and job performance. While a large number of personality inventories have been used in leader assessment, two of the most prominent include the California Psychological Inventory (CPI; Gough, 1975, 1984) and the Hogan Personality Inventory (HPI; Hogan & Hogan, 1995, 2007). Gough (1984) created the Managerial Potential Scale (MPS) from the larger CPI. Young, Arthur, and Finch (2000) found that the MPS significantly predicted performance ratings among 566 middle to upper level managers in various Fortune 500 companies. Anderson (2007) found correlations of 41 and 45 between the CPI and ratings of performance in sales executives and accounting managers, respectively. Hogan and Hogan (2007) reported significant validities for four of the HPI scales in predicting the performance of managers and executives. Hogan and Hogan (1995;

2001) also argued that personality flaws that can derail leaders should also be assessed when determining leader effectiveness (see also Hogan & Kaiser, 2005). 43 Accordingly, Hogan and Hogan (1995) developed the Hogan Development Survey (HDS) to assess personality correlates of potential managerial incompetence. While studies linking these attributes to poor executive performance are relatively limited compared to those on the FFM, some research has indicated support for using the HDS along with the HPI in executive assessment and selection (Fleming. 2004; Hass & Lemming, 2008; Hogan & Kaiser, 2008; Najar, Holland, Van Landuyt, 2004). Research on the “dark side of leadership” (Hogan & Hogan, 2001) corresponds with a significant recent increase in the use of integrity tests by organizations in assessments of managers and executives (Bernthal & Erker, 2005; Howard, 2007). In light of the scandals at Enron and other major corporations, the use of such tests

would seem appropriate. Some research studies have provided support for the validity and potential use of such tests for selection. Ones and Viswesvaran (2001; see also Ones, Viswesvaran, and Schmidt, 1993) reported criterion-related validities of .41 and 28 between integrity tests and supervisor ratings and production records, respectively. However, a recent legal ruling has raised some questions about the use of integrity tests (Heller, 2005), possibly portending some limitations on their use. Leadership potential. A number of inventories measure sets of leadership styles, skills and strengths, either as part of 360 degree assessments, or as solely self-administered tests. Examples of these tests include the Leader Career Battery (Development Dimensions International, 2007), Prospector (Spreitzer, et al., 1997; distributed by Center for Creative Leadership), the Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI; Kouzes & Posner, 1987; 1995), the Leadership Versatility Index (LVI; Kaiser &

Kaplan, 2008), and a number of 360-degree instruments from the Center for Creative Leadership (Executive Dimensions, Benchmarks, Prospector, 360 By Design, Campbell Leadership Inventory, and Skillscope). These measures 44 assess the strengths rising leaders can potentially bring to new or higher level executive positions. The 360-degree or multirater versions of these scales request ratings, not only from the leader, but also from that person’s supervisors/superiors, peers, and subordinates. Research on the use of leadership potential measures in executive selection is mixed. Howard (2007) asserted that tests of the leadership styles of initiating structure and consideration had “no established validity” presumably for selection purposes (p. 24) She noted somewhat stronger, but still weak validities for measures of transformational leadership. These kinds of measures have been used more appropriately in leadership research or as part of leader development programs (London, et