Please log in to read this in our online viewer!

Please log in to read this in our online viewer!

No comments yet. You can be the first!

Content extract

REMOVABLE PROSTHODONTICS REMOVABLE PROSTHODONTICS Improving Aesthetics in Patients with Complete Dentures Arshad Ali and David Hollisey-McLean Abstract: An increasing number of patients with complete dentures are requesting improvements in the aesthetics of their dentures. This paper considers methods of improving aesthetics, using the information available from the existing complete dentures, pre-extraction records and resin stains. Dent Update 1999; 26: 198-202 Clinical Relevance: This paper seeks to provide the dentist with details of clinical and laboratory techniques for improving the aesthetics of complete dentures. T he expectations of our patients are rising and many who wear dentures are requesting better aesthetics.1 However, the vast majority of dentures being produced still fail to look natural and individualized, but rather conform to the image of the ‘British standard’ denture, the features of which have been described by Besford.1 These include a ‘textbook’

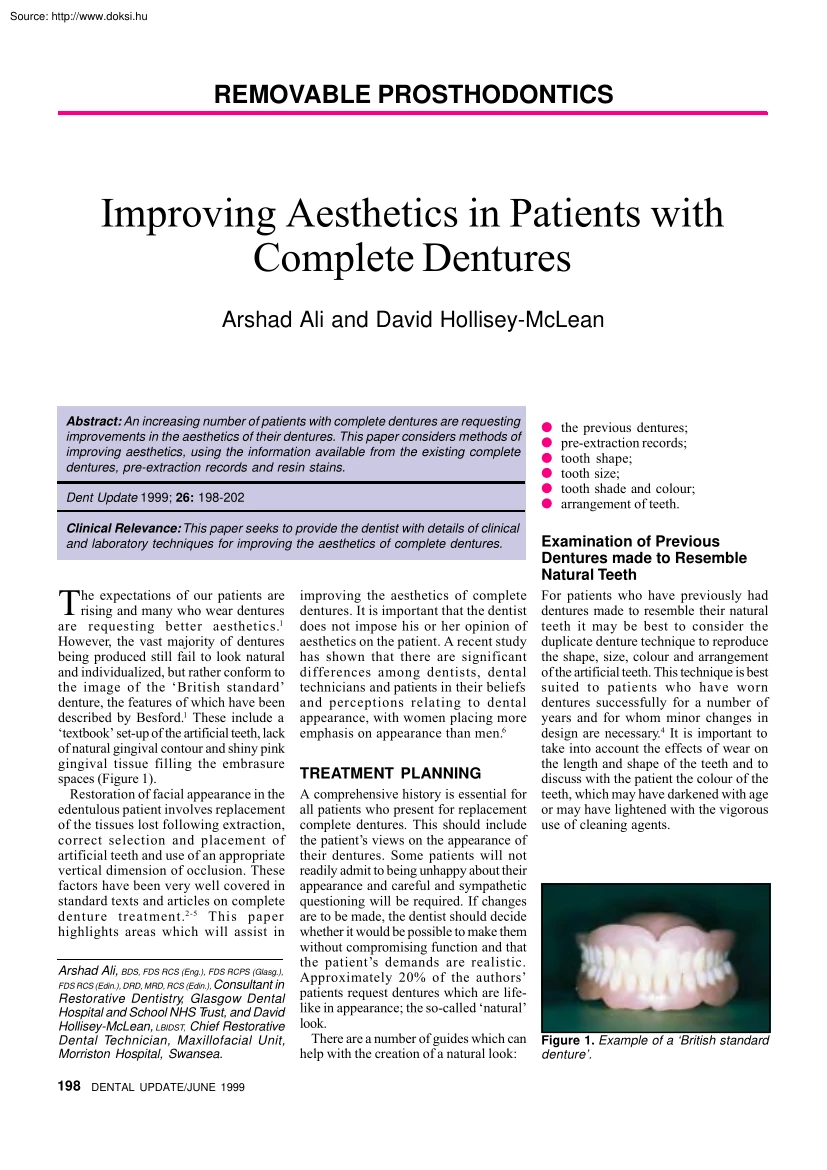

set-up of the artificial teeth, lack of natural gingival contour and shiny pink gingival tissue filling the embrasure spaces (Figure 1). Restoration of facial appearance in the edentulous patient involves replacement of the tissues lost following extraction, correct selection and placement of artificial teeth and use of an appropriate vertical dimension of occlusion. These factors have been very well covered in standard texts and articles on complete denture treatment.2-5 This paper highlights areas which will assist in Arshad Ali, BDS, FDS RCS (Eng.), FDS RCPS (Glasg), FDS RCS (Edin.), DRD, MRD, RCS (Edin), Consultant in Restorative Dentistry, Glasgow Dental Hospital and School NHS Trust, and David Hollisey-McLean, LBIDST, Chief Restorative Dental Technician, Maxillofacial Unit, Morriston Hospital, Swansea. 198 DENTAL UPDATE/JUNE 1999 improving the aesthetics of complete dentures. It is important that the dentist does not impose his or her opinion of aesthetics on the patient. A

recent study has shown that there are significant differences among dentists, dental technicians and patients in their beliefs and perceptions relating to dental appearance, with women placing more emphasis on appearance than men.6 TREATMENT PLANNING A comprehensive history is essential for all patients who present for replacement complete dentures. This should include the patient’s views on the appearance of their dentures. Some patients will not readily admit to being unhappy about their appearance and careful and sympathetic questioning will be required. If changes are to be made, the dentist should decide whether it would be possible to make them without compromising function and that the patient’s demands are realistic. Approximately 20% of the authors’ patients request dentures which are lifelike in appearance; the so-called ‘natural’ look. There are a number of guides which can help with the creation of a natural look: the previous dentures; pre-extraction records;

tooth shape; tooth size; tooth shade and colour; arrangement of teeth. Examination of Previous Dentures made to Resemble Natural Teeth For patients who have previously had dentures made to resemble their natural teeth it may be best to consider the duplicate denture technique to reproduce the shape, size, colour and arrangement of the artificial teeth. This technique is best suited to patients who have worn dentures successfully for a number of years and for whom minor changes in design are necessary.4 It is important to take into account the effects of wear on the length and shape of the teeth and to discuss with the patient the colour of the teeth, which may have darkened with age or may have lightened with the vigorous use of cleaning agents. Figure 1. Example of a ‘British standard denture’. REMOVABLE PROSTHODONTICS Pre-extraction Records Most patients will be able to produce photographs from which the dentist and technician can get some information to help them

produce dentures closely resembling the natural dentition. This can include information on the shape, size and colour of the teeth, the presence of diastemas, spacing, crowding and, possibly, the location of missing teeth. Study casts taken before extraction (if available) will also help in producing a natural appearance. Some dentists have incorporated patients’ natural anterior teeth in their partial or complete denture and have found good patient acceptance of the technique.7 If neither pre-extraction records nor previous dentures are available, it will be necessary to select teeth according to other guides. Tooth Shape There is little evidence to support the suggestion of Leon Williams that facial and tooth form can be classified into square, tapering or ovoid.8 However, use of this classification can produce acceptable results and most manufacturers of artificial teeth fabricate moulds related to it. Frush and Fisher9,10 considered dentogenic factors when selecting tooth form

and suggested selective reshaping of artificial teeth to account for the influence of age, sex and personalityfor example, the use of square angular teeth for men and curved rounded teeth for women. These were also the preferred tooth forms of the dentists, dental technicians and patients in the study referred to earlier.6 Tooth Size In general terms larger people have larger teeth and men usually have larger teeth than women. The average total width of the upper anterior teeth is 46 mm. However, many manufacturers produce teeth which are smaller than natural teeth, which results in a poor appearance with excessive display of anterior and premolar teeth. A commonly used clinical method of selecting the upper anterior teeth is to measure the trimmed record block on which the canine lines have been marked (at the level of the ala of the nose on each side) with a flexible ruler and then to select the appropriate width of tooth from the manufacturer’s mould chart. The length of the

teeth and the amount of tooth displayed at rest and on smiling is a very individual feature. As a guide, approximately 2 to 3 mm of the upper central incisors will be visible at rest in a younger patient, although this reduces with age. From an aesthetic point of view, the height of the upper premolars should be adequate to avoid a ‘step’ between the necks of the canines and premolars. Tooth Shade In general, women prefer lighter teeth than men.6 It is best to choose a basic colour in natural daylight from a northfacing window or under colour-corrected light. This should be followed by selecting the lightness or darkness of the teeth to correspond to the complexion, hair, skin and eye colour. The chosen shade tab should be moistened and tried in under the upper lip in the correct position. It is important that the dentist lets the patient make the final decision and does not impose his or her own views upon the patient. A common practice to improve the appearance is to use

artificial teeth of slightly different shades with the incisor teeth being lighter than the canines. Tooth Arrangement Dental students and technicians are trained to set up teeth in an ideal occlusion. However, varying the arrangement of teeth will produce a better aesthetic result. Setting the upper anterior teeth to follow the curve of the smiling lower lip, utilization of spacing, crowding and diastemas can help to individualize the denture. Ageing changes include: changes to colour; periodontal changes; and loss of tooth surface. Colour of Teeth Teeth will darken with age due to a number of factors, including deposition of secondary dentine, the presence of caries and restorations, and non-vitality. Older patients should be informed of this and encouraged to consider choosing a darker shade of artificial teeth. Periodontal Changes Periodontal changes which may occur with age include the following: gingival inflammation; oedema with loss of stippling; recession due to loss

of attachment; it is usual to see some blunting of the interdental papillae with the appearance of interdental spaces and a variable amount of exposure of the root surfaces. These changes can be reproduced in complete dentures and will help to improve the aesthetics, especially if the gingival tissues and flanges are visible on speaking or smiling widely. In such cases it is important to reproduce the natural anatomy of the gingival and alveolar tissues with thickening of the gingival margins, shaping of the interdental papilla, and creation of root eminences which are most prominent around the canine teeth. Loss of Tooth Surface Tooth surface is lost from the natural dentition to a varying degree, depending on many factorssuch as parafunctional habits, diet, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and vigorous oral hygiene procedures. Changes due to Ageing Many patients must be educated in the ageing changes which occur in the natural dentition, all of which can be reproduced to the required

degree in complete dentures. Showing the patient examples of processed dentures and photographs or clinical slides with different arrangements of teeth and ageing changes can help the patient to decide on the features which should be incorporated in the complete dentures. Figure 2. Complete upper denture with Minute Stains applied to the artificial teeth. 1999 JUNE/DENTAL UPDATE 199 REMOVABLE PROSTHODONTICS by Procare, Bradford) are resin pigments suspended in a varnish dissolved in butanone. They are applied with a fine paintbrush and protected with a clear glaze. The stains are available in seven different colours to enable production of a wide range of characterizations of teeth and gum tissue (Figure 2). It is best to apply these stains after the denture has been processed and polished as they are easily removed during polishing. They can also be applied at the chairside, which gives the patient an opportunity to assess the appearance. Minute Stains are easily modified or

removed if necessary. Figure 3. Application of Kayon denture stains into the mould. Attrition can be reproduced easily by reducing the incisal edges of the artificial teeth using acrylic burs at low speed. The reduction should incline upwards from labial to palatal on the upper teeth and will reduce the length of the teeth, which should be taken into account when selecting the artificial teeth. Tooth reduction should be carried out before the try-in stage to avoid problems with the occlusion anteriorly. STAINING A number of systems are available to produce naturalistic staining of prosthetic teeth, gingival tissues and flanges. Minute Stains Minute Stains (George Taub Products, New Jersey, USA; distributed in the UK Kayon Denture Stains These stains (Kay See Dental Manufacturing Company, Kansas City, USA; distributed in the UK by Plas-Dent Limited, Smethwick, West Midlands) can be used to stain the gingival areas and flanges of the denture.11 They consist of a range of shades that

can be blended to produce the desired colours. The denture is invested and the wax boiled out in the usual manner. The acrylic powders are sifted into the denture mould and localized with monomer which is dispensed from a syringe (Figure 3). This is allowed to partially cure before the remainder of the acrylic is introduced into the mould. It is possible using these stains to produce features of gingival inflammation, a pale pink colour over alveolar prominences, and other similar effects in the gingival tissues and flanges of the denture. They are especially useful in non-Caucasian patients, who often have extensive melanin deposits, mainly in the attached gingiva with smaller amounts in the free and marginal gingiva. Figure 6. The maxillary denture in place The authors have produced a gingival/ mucosal shade guide for selecting the most appropriate shade for the patient and a diagram which maps out the areas to be stained with each colour. As the colours are intrinsic to the

denture they are permanent in nature (compared with the externally applied stains, which are lost in time). Dreve Lightpaint-on Resin Colouring System This system (produced by Dreve Dentamid GmbH; distributed in the UK by Panadent Limited, London) has 12 resin colour pigments, which are mixed with a lightsensitive methylmethacrylate carrier to aid bonding to denture teeth and base. The stains are applied using a very fine paint brush and are cured in a light box. To help preserve the effects the surface is covered with a clear light-cured varnish (Figures 4 and 5). This system, like the Minute Stains, can be applied at the chairside and light-cured after the patient approves the appearance. Coloration from both the Minute and Dreve Stains is lost over a period of six to twelve months due to wear, but the dentures can be re-stained. In time the artificial stains are replaced with natural stains. CASE STUDY Figure 4. Application of Dreve Figure 5 Complete dentures with teeth,

Lightpaint-on resins to the complete gingival tissues and flanges stained denture. with the Dreve system. 200 DENTAL UPDATE/JUNE 1999 The following case demonstrates the use of some of the techniques outlined above. A 65-year-old man was referred for treatment as he was unhappy with the aesthetics of his replacement upper denture, which had all the features of a ‘British standard’ denture. He was edentulous in the upper arch and partially dentate in the lower arch. The remaining natural teeth and gingival tissues REMOVABLE PROSTHODONTICS demonstrated darkening of the natural teeth, tooth surface loss and gingival inflammation with recession of the gingival tissues. Treatment involved construction of a complete upper denture and partial lower denture, incorporating the features of the patient’s natural dentition mentioned above to improve the aesthetics. Photographs and study casts helped in selection of the shape and size of the upper teeth and in the tooth arrangement. A

gingival/mucosal shade map was recorded and Kayon denture stains were used to stain the flanges and gingival tissues. The Dreve Lightpaint-on resin colouring system was used to stain the acrylic teeth. The aesthetic outcome is shown in Figure 6. SUMMARY This paper outlines methods of improving the aesthetics of complete dentures with the aim of constructing dentures which are both functional and have a natural appearance. This will require very close collaborative teamwork involving the dentist, technician and the patient. With practice, the techniques described can be incorporated into treatment procedures with relative ease and, in our experience, result in better acceptance of the denture by the patient. References 1. Besford JN Restoring the appearance of the edentulous person. Restor Dent 1984; 1: 17-27. 2. Watt DM, MacGregor AR Designing Complete Dentures . Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1976 3. Lamb DJ Appearance and Aesthetics in Denture Practice. Bristol: Wright, 1987 4. Packer

ME, Scott BJJ, Watson RM The challenge of replacing complete dentures: Part 1. Dent Update 1996; 23: 226-234 5. Packer ME, Scott BJJ, Watson RM The challenge of replacing complete dentures: Part 2. Dent Update 1996; 23: 276-281 6. Carlsson GE, Wagner I-V, Odman P et al. An international comparative multicenter study of assessment of dental appearance using computer-aided image manipulation. Int J Prosthodont 1998; 18: 246-254. 7. Cardoso AC, Arcari GM, Zendron MV, Magini RS. The use of natural teeth to make removable partial prostheses and complete prostheses: Case reports. Quint Int 1994; 25: 239-243. 8. L e o n W i l l i a m s J T h e e s t h e t i c a n d anatomical basis of dental prosthesis. Dent Cosmos 1911; 1: 1-26. 9. Frush JP, Fisher RD How dentogenic restorations interpret the sex factor . J Prosthet Dent 1956; 6: 160-172. 10. Frush JP, Fisher RD How dentogenic restorations interpret the personality factor . J Prosthet Dent 1956; 6: 441-449. 11. Pound E Personalised Denture

Procedures. Dentists Manual Anaheim CA: Denar Corporation, 1973; pp.81-87 Abstracts 1. FIRST THE BAD NEWS Direct Placement Gallium Restorative Alloy: A 3-year Study. JW Osborne and TB Summit. Quintessence International 1999; 30: 49-53. This issue introduces a new feature abstracts of articles from the current dental literature which are particularly relevant to the general dental practitioner. They are being prepared by Peter Carrotte, MDS, LDS, MEd, who has recently joined the academic staff in the Department of Adult Dental Care at Glasgow Dental School. Having gained wide experience in general dental practice, Peter was previously a lecturer at Sheffield for several years, and has spent two years working with the MDU. Apart from continuing professional development, his particular interest is endodontics, and he is currently the President of the British Endodontic Society. 202 DENTAL UPDATE/JUNE 1999 Whilst our patients continue to complain about the aesthetics of amalgam

fillings, and to question their safety, materials scientists continue to search for viable alternatives. Laboratory studies had suggested that one gallium alloy may be suitable for clinical practice, and this paper reports the results of a three-year study. Sadly, we will not be beating a path to their door with an open cheque book. Not only was the material clinically challenging to place, but these and other results suggest serious concerns over postoperative sensitivity; fracture of both the material and tooth tissue; high rates of both tarnish and, more seriously, pulpal necrosis. And, of course, the restorations are still grey! 2. AND NOW THE GOOD NEWS Clinical Evaluation of a Posterior Composite 10-year Report. A Raskin et al Journal of Dentistry 1999; 27: 13-19. This report highlights the problems in assessing new materials clinically, with the rapid and continuing development of materials science. The composite restorative material selected was Occlusin (ICI, Macclesfield, UK)

which has long since been left behind by new developments. In spite of this, the results are encouraging. Over the 10-year period a number of patients were lost from the study, but it is estimated that between 50 and 60% of the class 1 and 2 restorations had survived, with a worst case scenario of 37% success. The main causes of failure were wear both occlusally and interproximally, with loss of interdental contacts. Recurrent caries was not found to be a significant problem. Interestingly, no significant difference was found between those restorations placed with or without the use of rubber dam. The report gives hope to those practitioners who have taken the time and trouble to learn the correct techniques involved in the placement of posterior composites. (How many amalgams did you have to do as an undergraduate before you were competent, and how many posterior composites have you done on a phantom head?) An interesting and thoughtprovoking article

set-up of the artificial teeth, lack of natural gingival contour and shiny pink gingival tissue filling the embrasure spaces (Figure 1). Restoration of facial appearance in the edentulous patient involves replacement of the tissues lost following extraction, correct selection and placement of artificial teeth and use of an appropriate vertical dimension of occlusion. These factors have been very well covered in standard texts and articles on complete denture treatment.2-5 This paper highlights areas which will assist in Arshad Ali, BDS, FDS RCS (Eng.), FDS RCPS (Glasg), FDS RCS (Edin.), DRD, MRD, RCS (Edin), Consultant in Restorative Dentistry, Glasgow Dental Hospital and School NHS Trust, and David Hollisey-McLean, LBIDST, Chief Restorative Dental Technician, Maxillofacial Unit, Morriston Hospital, Swansea. 198 DENTAL UPDATE/JUNE 1999 improving the aesthetics of complete dentures. It is important that the dentist does not impose his or her opinion of aesthetics on the patient. A

recent study has shown that there are significant differences among dentists, dental technicians and patients in their beliefs and perceptions relating to dental appearance, with women placing more emphasis on appearance than men.6 TREATMENT PLANNING A comprehensive history is essential for all patients who present for replacement complete dentures. This should include the patient’s views on the appearance of their dentures. Some patients will not readily admit to being unhappy about their appearance and careful and sympathetic questioning will be required. If changes are to be made, the dentist should decide whether it would be possible to make them without compromising function and that the patient’s demands are realistic. Approximately 20% of the authors’ patients request dentures which are lifelike in appearance; the so-called ‘natural’ look. There are a number of guides which can help with the creation of a natural look: the previous dentures; pre-extraction records;

tooth shape; tooth size; tooth shade and colour; arrangement of teeth. Examination of Previous Dentures made to Resemble Natural Teeth For patients who have previously had dentures made to resemble their natural teeth it may be best to consider the duplicate denture technique to reproduce the shape, size, colour and arrangement of the artificial teeth. This technique is best suited to patients who have worn dentures successfully for a number of years and for whom minor changes in design are necessary.4 It is important to take into account the effects of wear on the length and shape of the teeth and to discuss with the patient the colour of the teeth, which may have darkened with age or may have lightened with the vigorous use of cleaning agents. Figure 1. Example of a ‘British standard denture’. REMOVABLE PROSTHODONTICS Pre-extraction Records Most patients will be able to produce photographs from which the dentist and technician can get some information to help them

produce dentures closely resembling the natural dentition. This can include information on the shape, size and colour of the teeth, the presence of diastemas, spacing, crowding and, possibly, the location of missing teeth. Study casts taken before extraction (if available) will also help in producing a natural appearance. Some dentists have incorporated patients’ natural anterior teeth in their partial or complete denture and have found good patient acceptance of the technique.7 If neither pre-extraction records nor previous dentures are available, it will be necessary to select teeth according to other guides. Tooth Shape There is little evidence to support the suggestion of Leon Williams that facial and tooth form can be classified into square, tapering or ovoid.8 However, use of this classification can produce acceptable results and most manufacturers of artificial teeth fabricate moulds related to it. Frush and Fisher9,10 considered dentogenic factors when selecting tooth form

and suggested selective reshaping of artificial teeth to account for the influence of age, sex and personalityfor example, the use of square angular teeth for men and curved rounded teeth for women. These were also the preferred tooth forms of the dentists, dental technicians and patients in the study referred to earlier.6 Tooth Size In general terms larger people have larger teeth and men usually have larger teeth than women. The average total width of the upper anterior teeth is 46 mm. However, many manufacturers produce teeth which are smaller than natural teeth, which results in a poor appearance with excessive display of anterior and premolar teeth. A commonly used clinical method of selecting the upper anterior teeth is to measure the trimmed record block on which the canine lines have been marked (at the level of the ala of the nose on each side) with a flexible ruler and then to select the appropriate width of tooth from the manufacturer’s mould chart. The length of the

teeth and the amount of tooth displayed at rest and on smiling is a very individual feature. As a guide, approximately 2 to 3 mm of the upper central incisors will be visible at rest in a younger patient, although this reduces with age. From an aesthetic point of view, the height of the upper premolars should be adequate to avoid a ‘step’ between the necks of the canines and premolars. Tooth Shade In general, women prefer lighter teeth than men.6 It is best to choose a basic colour in natural daylight from a northfacing window or under colour-corrected light. This should be followed by selecting the lightness or darkness of the teeth to correspond to the complexion, hair, skin and eye colour. The chosen shade tab should be moistened and tried in under the upper lip in the correct position. It is important that the dentist lets the patient make the final decision and does not impose his or her own views upon the patient. A common practice to improve the appearance is to use

artificial teeth of slightly different shades with the incisor teeth being lighter than the canines. Tooth Arrangement Dental students and technicians are trained to set up teeth in an ideal occlusion. However, varying the arrangement of teeth will produce a better aesthetic result. Setting the upper anterior teeth to follow the curve of the smiling lower lip, utilization of spacing, crowding and diastemas can help to individualize the denture. Ageing changes include: changes to colour; periodontal changes; and loss of tooth surface. Colour of Teeth Teeth will darken with age due to a number of factors, including deposition of secondary dentine, the presence of caries and restorations, and non-vitality. Older patients should be informed of this and encouraged to consider choosing a darker shade of artificial teeth. Periodontal Changes Periodontal changes which may occur with age include the following: gingival inflammation; oedema with loss of stippling; recession due to loss

of attachment; it is usual to see some blunting of the interdental papillae with the appearance of interdental spaces and a variable amount of exposure of the root surfaces. These changes can be reproduced in complete dentures and will help to improve the aesthetics, especially if the gingival tissues and flanges are visible on speaking or smiling widely. In such cases it is important to reproduce the natural anatomy of the gingival and alveolar tissues with thickening of the gingival margins, shaping of the interdental papilla, and creation of root eminences which are most prominent around the canine teeth. Loss of Tooth Surface Tooth surface is lost from the natural dentition to a varying degree, depending on many factorssuch as parafunctional habits, diet, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and vigorous oral hygiene procedures. Changes due to Ageing Many patients must be educated in the ageing changes which occur in the natural dentition, all of which can be reproduced to the required

degree in complete dentures. Showing the patient examples of processed dentures and photographs or clinical slides with different arrangements of teeth and ageing changes can help the patient to decide on the features which should be incorporated in the complete dentures. Figure 2. Complete upper denture with Minute Stains applied to the artificial teeth. 1999 JUNE/DENTAL UPDATE 199 REMOVABLE PROSTHODONTICS by Procare, Bradford) are resin pigments suspended in a varnish dissolved in butanone. They are applied with a fine paintbrush and protected with a clear glaze. The stains are available in seven different colours to enable production of a wide range of characterizations of teeth and gum tissue (Figure 2). It is best to apply these stains after the denture has been processed and polished as they are easily removed during polishing. They can also be applied at the chairside, which gives the patient an opportunity to assess the appearance. Minute Stains are easily modified or

removed if necessary. Figure 3. Application of Kayon denture stains into the mould. Attrition can be reproduced easily by reducing the incisal edges of the artificial teeth using acrylic burs at low speed. The reduction should incline upwards from labial to palatal on the upper teeth and will reduce the length of the teeth, which should be taken into account when selecting the artificial teeth. Tooth reduction should be carried out before the try-in stage to avoid problems with the occlusion anteriorly. STAINING A number of systems are available to produce naturalistic staining of prosthetic teeth, gingival tissues and flanges. Minute Stains Minute Stains (George Taub Products, New Jersey, USA; distributed in the UK Kayon Denture Stains These stains (Kay See Dental Manufacturing Company, Kansas City, USA; distributed in the UK by Plas-Dent Limited, Smethwick, West Midlands) can be used to stain the gingival areas and flanges of the denture.11 They consist of a range of shades that

can be blended to produce the desired colours. The denture is invested and the wax boiled out in the usual manner. The acrylic powders are sifted into the denture mould and localized with monomer which is dispensed from a syringe (Figure 3). This is allowed to partially cure before the remainder of the acrylic is introduced into the mould. It is possible using these stains to produce features of gingival inflammation, a pale pink colour over alveolar prominences, and other similar effects in the gingival tissues and flanges of the denture. They are especially useful in non-Caucasian patients, who often have extensive melanin deposits, mainly in the attached gingiva with smaller amounts in the free and marginal gingiva. Figure 6. The maxillary denture in place The authors have produced a gingival/ mucosal shade guide for selecting the most appropriate shade for the patient and a diagram which maps out the areas to be stained with each colour. As the colours are intrinsic to the

denture they are permanent in nature (compared with the externally applied stains, which are lost in time). Dreve Lightpaint-on Resin Colouring System This system (produced by Dreve Dentamid GmbH; distributed in the UK by Panadent Limited, London) has 12 resin colour pigments, which are mixed with a lightsensitive methylmethacrylate carrier to aid bonding to denture teeth and base. The stains are applied using a very fine paint brush and are cured in a light box. To help preserve the effects the surface is covered with a clear light-cured varnish (Figures 4 and 5). This system, like the Minute Stains, can be applied at the chairside and light-cured after the patient approves the appearance. Coloration from both the Minute and Dreve Stains is lost over a period of six to twelve months due to wear, but the dentures can be re-stained. In time the artificial stains are replaced with natural stains. CASE STUDY Figure 4. Application of Dreve Figure 5 Complete dentures with teeth,

Lightpaint-on resins to the complete gingival tissues and flanges stained denture. with the Dreve system. 200 DENTAL UPDATE/JUNE 1999 The following case demonstrates the use of some of the techniques outlined above. A 65-year-old man was referred for treatment as he was unhappy with the aesthetics of his replacement upper denture, which had all the features of a ‘British standard’ denture. He was edentulous in the upper arch and partially dentate in the lower arch. The remaining natural teeth and gingival tissues REMOVABLE PROSTHODONTICS demonstrated darkening of the natural teeth, tooth surface loss and gingival inflammation with recession of the gingival tissues. Treatment involved construction of a complete upper denture and partial lower denture, incorporating the features of the patient’s natural dentition mentioned above to improve the aesthetics. Photographs and study casts helped in selection of the shape and size of the upper teeth and in the tooth arrangement. A

gingival/mucosal shade map was recorded and Kayon denture stains were used to stain the flanges and gingival tissues. The Dreve Lightpaint-on resin colouring system was used to stain the acrylic teeth. The aesthetic outcome is shown in Figure 6. SUMMARY This paper outlines methods of improving the aesthetics of complete dentures with the aim of constructing dentures which are both functional and have a natural appearance. This will require very close collaborative teamwork involving the dentist, technician and the patient. With practice, the techniques described can be incorporated into treatment procedures with relative ease and, in our experience, result in better acceptance of the denture by the patient. References 1. Besford JN Restoring the appearance of the edentulous person. Restor Dent 1984; 1: 17-27. 2. Watt DM, MacGregor AR Designing Complete Dentures . Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1976 3. Lamb DJ Appearance and Aesthetics in Denture Practice. Bristol: Wright, 1987 4. Packer

ME, Scott BJJ, Watson RM The challenge of replacing complete dentures: Part 1. Dent Update 1996; 23: 226-234 5. Packer ME, Scott BJJ, Watson RM The challenge of replacing complete dentures: Part 2. Dent Update 1996; 23: 276-281 6. Carlsson GE, Wagner I-V, Odman P et al. An international comparative multicenter study of assessment of dental appearance using computer-aided image manipulation. Int J Prosthodont 1998; 18: 246-254. 7. Cardoso AC, Arcari GM, Zendron MV, Magini RS. The use of natural teeth to make removable partial prostheses and complete prostheses: Case reports. Quint Int 1994; 25: 239-243. 8. L e o n W i l l i a m s J T h e e s t h e t i c a n d anatomical basis of dental prosthesis. Dent Cosmos 1911; 1: 1-26. 9. Frush JP, Fisher RD How dentogenic restorations interpret the sex factor . J Prosthet Dent 1956; 6: 160-172. 10. Frush JP, Fisher RD How dentogenic restorations interpret the personality factor . J Prosthet Dent 1956; 6: 441-449. 11. Pound E Personalised Denture

Procedures. Dentists Manual Anaheim CA: Denar Corporation, 1973; pp.81-87 Abstracts 1. FIRST THE BAD NEWS Direct Placement Gallium Restorative Alloy: A 3-year Study. JW Osborne and TB Summit. Quintessence International 1999; 30: 49-53. This issue introduces a new feature abstracts of articles from the current dental literature which are particularly relevant to the general dental practitioner. They are being prepared by Peter Carrotte, MDS, LDS, MEd, who has recently joined the academic staff in the Department of Adult Dental Care at Glasgow Dental School. Having gained wide experience in general dental practice, Peter was previously a lecturer at Sheffield for several years, and has spent two years working with the MDU. Apart from continuing professional development, his particular interest is endodontics, and he is currently the President of the British Endodontic Society. 202 DENTAL UPDATE/JUNE 1999 Whilst our patients continue to complain about the aesthetics of amalgam

fillings, and to question their safety, materials scientists continue to search for viable alternatives. Laboratory studies had suggested that one gallium alloy may be suitable for clinical practice, and this paper reports the results of a three-year study. Sadly, we will not be beating a path to their door with an open cheque book. Not only was the material clinically challenging to place, but these and other results suggest serious concerns over postoperative sensitivity; fracture of both the material and tooth tissue; high rates of both tarnish and, more seriously, pulpal necrosis. And, of course, the restorations are still grey! 2. AND NOW THE GOOD NEWS Clinical Evaluation of a Posterior Composite 10-year Report. A Raskin et al Journal of Dentistry 1999; 27: 13-19. This report highlights the problems in assessing new materials clinically, with the rapid and continuing development of materials science. The composite restorative material selected was Occlusin (ICI, Macclesfield, UK)

which has long since been left behind by new developments. In spite of this, the results are encouraging. Over the 10-year period a number of patients were lost from the study, but it is estimated that between 50 and 60% of the class 1 and 2 restorations had survived, with a worst case scenario of 37% success. The main causes of failure were wear both occlusally and interproximally, with loss of interdental contacts. Recurrent caries was not found to be a significant problem. Interestingly, no significant difference was found between those restorations placed with or without the use of rubber dam. The report gives hope to those practitioners who have taken the time and trouble to learn the correct techniques involved in the placement of posterior composites. (How many amalgams did you have to do as an undergraduate before you were competent, and how many posterior composites have you done on a phantom head?) An interesting and thoughtprovoking article

Just like you draw up a plan when you’re going to war, building a house, or even going on vacation, you need to draw up a plan for your business. This tutorial will help you to clearly see where you are and make it possible to understand where you’re going.

Just like you draw up a plan when you’re going to war, building a house, or even going on vacation, you need to draw up a plan for your business. This tutorial will help you to clearly see where you are and make it possible to understand where you’re going.