Please log in to read this in our online viewer!

Please log in to read this in our online viewer!

No comments yet. You can be the first!

What did others read after this?

Content extract

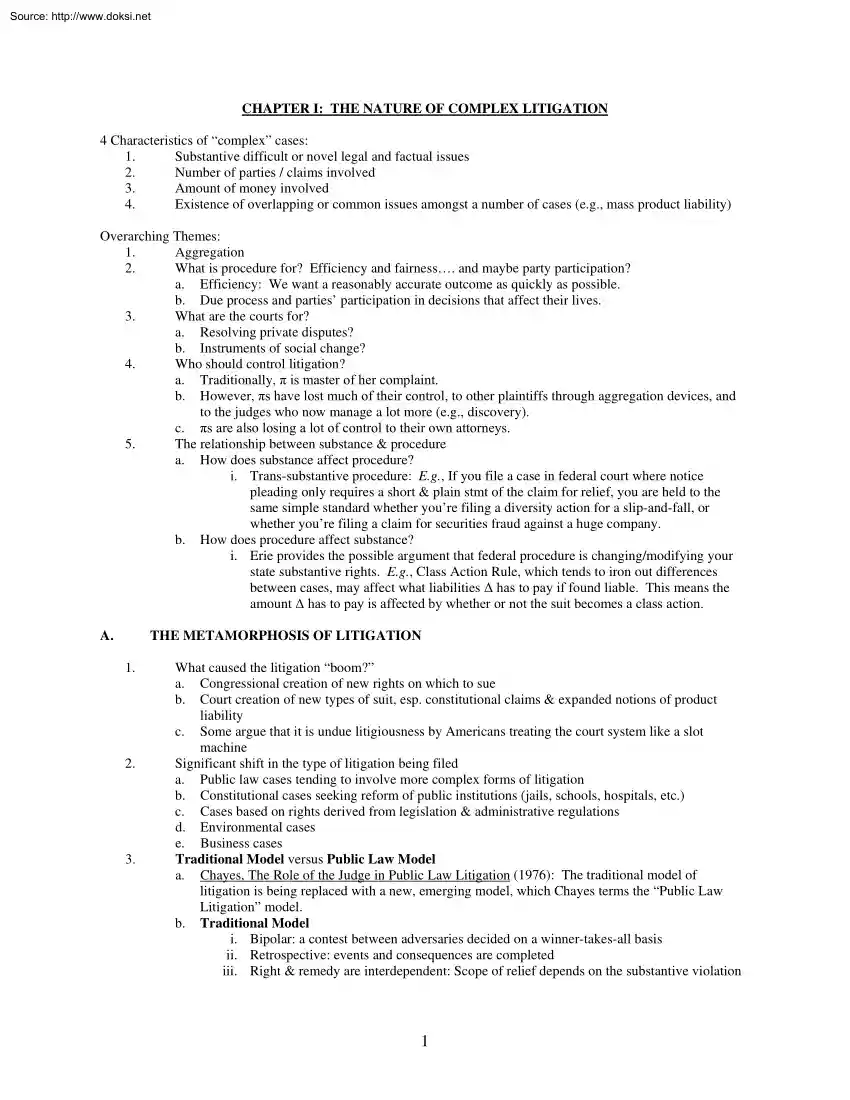

Source: http://www.doksinet CHAPTER I: THE NATURE OF COMPLEX LITIGATION 4 Characteristics of “complex” cases: 1. Substantive difficult or novel legal and factual issues 2. Number of parties / claims involved 3. Amount of money involved 4. Existence of overlapping or common issues amongst a number of cases (e.g, mass product liability) Overarching Themes: 1. Aggregation 2. What is procedure for? Efficiency and fairness. and maybe party participation? a. Efficiency: We want a reasonably accurate outcome as quickly as possible b. Due process and parties’ participation in decisions that affect their lives 3. What are the courts for? a. Resolving private disputes? b. Instruments of social change? 4. Who should control litigation? a. Traditionally, π is master of her complaint b. However, πs have lost much of their control, to other plaintiffs through aggregation devices, and to the judges who now manage a lot more (e.g, discovery) c. πs are also losing a lot of control to their

own attorneys 5. The relationship between substance & procedure a. How does substance affect procedure? i. Trans-substantive procedure: Eg, If you file a case in federal court where notice pleading only requires a short & plain stmt of the claim for relief, you are held to the same simple standard whether you’re filing a diversity action for a slip-and-fall, or whether you’re filing a claim for securities fraud against a huge company. b. How does procedure affect substance? i. Erie provides the possible argument that federal procedure is changing/modifying your state substantive rights. Eg, Class Action Rule, which tends to iron out differences between cases, may affect what liabilities Δ has to pay if found liable. This means the amount Δ has to pay is affected by whether or not the suit becomes a class action. A. THE METAMORPHOSIS OF LITIGATION 1. 2. 3. What caused the litigation “boom?” a. Congressional creation of new rights on which to sue b. Court creation

of new types of suit, esp constitutional claims & expanded notions of product liability c. Some argue that it is undue litigiousness by Americans treating the court system like a slot machine Significant shift in the type of litigation being filed a. Public law cases tending to involve more complex forms of litigation b. Constitutional cases seeking reform of public institutions (jails, schools, hospitals, etc) c. Cases based on rights derived from legislation & administrative regulations d. Environmental cases e. Business cases Traditional Model versus Public Law Model a. Chayes, The Role of the Judge in Public Law Litigation (1976): The traditional model of litigation is being replaced with a new, emerging model, which Chayes terms the “Public Law Litigation” model. b. Traditional Model i. Bipolar: a contest between adversaries decided on a winner-takes-all basis ii. Retrospective: events and consequences are completed iii. Right & remedy are interdependent: Scope of

relief depends on the substantive violation 1 Source: http://www.doksinet 4. 5. iv. Self-contained episode: Impact of the judgment affects on the parties at hand, and entry of the judgment ends the court’s involvement v. Party-initiated and/or party-controlled: Responsibility for the organization and development of the case falls to the parties. c. Public Law Model i. “Sprawling and amorphous” party structure ii. Not necessarily adversary; much mediation and negotiation iii. Judge is dominant in organizing and guiding the case iv. Judge became the creator and manager of “complex forms of ongoing relief” that affect people outside the scope of the lawsuit and require the court’s continued involvement (e.g, school desegregation, prisoner rights, employment discrimination) Mass Tort Litigation a. Chayes’ model suited the 1960’s and 1970’s, but was outdated by the 80’s and 90’s when modern mass tort litigation began to arise. b. Made possible by the procedural

reforms of 1938, which introduced joinder devices c. Class action rule was amended in 1966 allowing for injunctive and declaratory relief Rule 23(b)(3) a. Is the goal efficiency, to allow courts and parties to handle many similar legal claims without requiring each individual bring his own suit? b. Is the goal enabling, to allow suits not possible on an individual basis to pursue social goals? c. Rand Institute for Civil Justice (2000) argues that it is inherently both: “Any change in court processes that provides more efficient means of litigating is likely to enable more litigation.” RIfCJ also argues that Rule 23 is inherently an enabling mechanism, even with its efficiencies. d. Business representatives claim class actions benefit the attorneys more than the plaintiffs, and that consumers end up paying for the increased litigation through increased product costs. e. Manufacturers claim that mass-product defect suits are often based on weak evidence and basically force a

settlement because of the huge financial risks associated with litigation. f. Consumer advocates claim that the mass suits serve a regulatory purpose, a check on business practices, but that they sometimes produce bad outcomes that benefit the attorneys more than the plaintiffs. CHAPTER II: JOINDER AND STRUCTURE OF SUIT IN A UNITARY FEDERAL FORUM Aggregation Devices to be looked at: (1) Joinder (2) Transfer (3) Consolidation (once all cases are transferred to a single district) (4) Class Action PERMISSIVE PARTY JOINDER Permissive Joinder: Rule 20. Those who may be joined 1. The claims arise from the same transaction / occurrence; AND 2. Raise at least one common question or law or fact 3. Consolidation: Rule 42. Where actions involving a common question of law or fact are pending before the same court, the court may order the actions to be consolidated into one action. Mosely v. General Motors Corp (1974): Permissive joinder requirements were met in a gender & race discrimination

case: 1. Transaction/Occurrence: A company policy that discriminated against blacks created a “system” of transactions/occurrences through which the individual πs were harmed. 2. Question of law/fact: Right to relief depends on whether each π was harmed by racial discrimination. Thus, Δ’s discriminatory conduct is a shared question of fact. The fact that the conduct may have affected each π in different ways is immaterial. What makes the case complex? The number and types of plaintiffs involved. 2 Source: http://www.doksinet All involved parties thought joinder was essential. Defense filed a motion for misjoinder, showing their concern for the scope of the case, and πs took an interlocutory appeal, showing their concern for the issue. The judge was clearly concerned as well, because the district judge has to essentially certify that it’s worth delaying litigation to get a ruling on that appeal. As the judge, when you’re deciding joinder issues, you have in front of

you only the pleadings. Should you require proof of meeting the Rule 20 requirements to allow a case to proceed? The evidence necessary to prove that may be in the hands of the other side. The dilemma is that it’s very hard to see at the outset whether the π’s offered structure of the case will actually work, and yet, procedurally, that’s precisely when you must decide. What should the injunction look like at the end of the case? If an injunction is meant to address a systemic problem of the company, does it not suggest that the current/other employees of GM are indispensable parties, since it is their work environment/relationship that will be affected by that injunction? Why did πs include the Union as a defendant? Because without the Union, you can’t get an injunctive change that will really restructure GM. Strategically, here is an example of a π’s lawyer shaping a lawsuit in relation to the relief they were after. That’s why π joined mulitple πs together and chose

to include the Union as Δ. You also see how the substance of the legal theory involved in the case drives the procedure involved in the case. Stanford v. Tennessee Valley Authority (1955): Basic Facts: π sued two separate companies for damages resulting by fluorine gas fumes emitted from Δs’ plants. Δ requested a misjoider ruling, or severance. Issue: The question becomes whether you can characterize the emission of fluorine gas from two separate plants as a single transaction or occurrence. In TN state court, these Δs couldn’t be bound together, but because there’s a federal rule on point (Rule 20) π can bind them. But judge has to apply TN substantive law, which says there is no theory of joint liability. Rule 42: Case not dismissed, because Rule 42 permits consolidation if a common question of law/fact is to be considered. Examples of such questions: (1) Is it a permanent or temporary nuisance?; (2) Are the fumes capable of and did they actually produce the damage

claimed?; and (3) Could Δ have used a device or different production methods to curb the production of the fumes? Order: Claims are severed EXCEPT that they will be tried before the same jury: separate complaints must be filed, separate pleadings, motions, verdicts and judgments. Will preserve for each Δ procedural advantages of separate trials, including the right to peremptory juror challenges. This is actually probably worse for Δs, since they are separate for the pretrial proceedings (don’t have access to each other’s discovery materials or depositions, for instance) but they have to be tried together, making it harder for them to point fingers at each other. What is Mosley was reversed, and a big company wants to sue a bunch of “little guys”? Cable company tries to sue everyone that had been getting illegal pay-per-view, for example. Court refused to allow them to meet the transaction test. Is that in conflict with Mosley? - Probably not, since it’s unlikely that the

cable-stealers were part of some organization or group that had a systematic policy of cable-stealing. Hall v. EI Du Pont Nemours & Co, Inc and Chance v EI Du Pont Nemours & Co, Inc (1972): Chance: Problem: πs cannot identify the manufacturer of the cap that injured their child. Apply Rule 20: (1) same transaction/occurrence, PLUS (2) common issue of law/fact. Joint Liability: Δs could be held responsible as a group under several theories of joint liability, including (1) concert of action creating dangerous circumstance; (2) enterprise liability; and (3) Summers v. Tice alternative liability. [Notes also mention (4) market share liability theory] Interplay of Substance & Procedure: You see Judge Weinstein reading the procedure very broadly to effectuate the substantive goals of the tort law. You see the judge in Mosley reading very broadly to effectuate the substance of the employment discrimination laws. Common Question of Law: Cannot be determined, as Judge required

briefs regarding NY’s choice of law statutes. For now, he assumes all the states will agree on their applicable tort law Common Question of Fact: YES. For example, whether Δ exercised joint control over labeling, whether Δs operated as joint enterprise with regard to labeling. 3 Source: http://www.doksinet Outcome: Permit πs to litigate the issue of joint activity in this court, then transfer the questions which turn on the particular facts of each accident to the federal districts in which accidents occured. Hall: Joint Liability: Not present here. Unlike Chance, the families here were not each suing all of the manufacturers. Rather, the Judge found that it was just “happenstance” that three families happened to be suing two of the same manufacturers. Unlike Chance, each π was claiming only against the manufacturer of the particular cap involved with their injury. Common Question of Law/Fact: Not present. Recovery will turn on questions of negligence and strict

liability, using specific evidence related to the separate circumstances of each instance. COMPULSORY PARTY JOINDER Rule 19: Necessary & Indispensable Parties: 1. Under Rule 19(a), the party is necessary if: a. No complete relief is available to current parties without the outsider, OR b. Outside party has an interest in the lawsuit that may be practically impaired (not legally impaired) by outcome of the lawsuit, OR c. Current party would be subject to multiple or inconsistent liabilities unless the outsider is joined 2. Is joinder feasible? a. Does the court have personal jurisdiction over the person? b. Does joinder destroy diversity? c. Improper venue? 3. If joinder is not feasible, go to Rule 19(b) to determine whether case should proceed without the outsider, or should be dismissed (“whether in equity and good conscience” the case can go forward without the outsider). a. Defendant’s Interest: Might Δ be subject to multiple or inconsistent liability? b. Outsider’s

Interest: To what extent might a judgment in the person’s absence be prejudicial to the outsider or other party? To what extent can prejudice be lessened or avoided? c. Plaintiff’s Interest: Will π have an adequate remedy (other forum where all parties may be sued) if the case is dismissed? Will judgment in the person’s absence be adequate? d. Society, etc’s Interest: Will dismissal or continuance impede the efficiency and functioning of the court? 4. Rule 12(b)(7) is a dismissal for failure to join an outsider under this Rule. π can usually file the suit elsewhere if it is dismissed under Rule 12(b)(7). Eldredge v. Carpenters 46 Northern California Counties JATC (1981): Basics: πs sued JATC, organization in charge of sending out the potential apprentices to potential employers. JATC was using a “hunting license” system, in which the apprentice had to find an employer willing to hire you, then go to the Union hall and get on the apprenticeship list and the official

apprenticeship program begins. πs contended these employers were not hiring women. Why did πs sue only JATC? Easier to sue the one body, rather than trying to sue 4,500 different employers. What is Δs strategy? JATC wanted all employers joined. JATC doesn’t make the hiring decisions; the employers do, so for π to get complete relief, the employers should be bound to a judgment. Besides Δ knows suing 4500 employers is difficult and cost-prohibitive, and would probably result in suit failure. Judge’s Perspective: The employers can dump JATC if they want; an injunction against JATC would be pointless. Thus, no complete relief can be accorded without the employers. Furthermore, the employers have a practical interest in the outcome of the injunction. The 19(b) Aspect: [The appellate court finds that 19(a) is not met, so they do not address 19(b).] INTERVENTION Intervention: Rule 24. Outsider puts himself into the litigation 1. Policy Issues: a. Do not want repeat litigation, BUT

b. Original litigants have a right to keep their litigations uncluttered 4 Source: http://www.doksinet 2. 3. 4. Intervention as Right: Rule 24(a). a. Must have direct, legally-protectable interest in the lawsuit, AND b. Must show that their interest will be practically impaired if intervention is refused, AND c. Must show that their interests are not already adequately represented by a current party Permissive Intervention: Rule 24(b). a. Only has to have a claim or defense with at least one common question of law or fact b. Highly discretionary Miscellaneous a. Strategically You should argue for Intervention as of Rightmakes a stronger argument at district level, and if the judge turns you down when you ask for permissive intervention, it is highly unlikely that the Court of Appeals will overturn that decision. You may pursue both versions of intervention at the same time. b. Timing The later you are in the lawsuit, the less likely a judge is to let an outsider intervene c. The

Catch-22 The outsider often doesn’t know that he needs to “get in” on the lawsuit until he sees the remedy and realize the remedy affects him. d. In diversity case, cannot intervene as π with someone from the same state If the intervener cannot enter the lawsuit without destroying diversity, then must look to Rule 19(b) to see if they must be joined and whether the suit should be dismissed or continued. e. Intervention gives persons all the rights as a party f. Intervention is the only joinder device where the outsider asks to be let in g. Courts read the “interest” requirement for Intervention more broadly than for compulsory joinder because they’d rather see a “volunteer” join a suit than someone be forced to do so. h. If an intervener who does not have standing wants to appeal a judgment where the parties do not wish to appeal, that intervener must show standing to pursue the appeal. Planned Parenthood v. Citizens for Community Action (1977): St. Paul City Council

voted 5 -2 in favor of an ordinance that created a moratorium on zoning for abortion facilities Planned Parenthood then files to enjoin the ordinance, and the action group of concerned citizens seeks to intervene. District Judge denied intervention Issue on appeal is whether the citizens were Interveners as of Right. (1) Direct, legally-protectable interest in the suit? Homeowners assert a property interest, that their property values will be affected by the abortion facility. (2) Practical impairment: economic interest will be impaired. (3) No adequate representation: city council is elected to represent the citizens. However, the interests with the municipality may conflict with the private homeowners’ interests. (Courts are pretty liberal with the “no adequate representation” prong.) Differences in strategy approaches and goals will be enough to say the current party is not an adequate representative. Martin v. Wilks (1989): 1st Lawsuit: NAACP & 7 individuals filed actions

against city and personnel board for violating Title VII by racially discriminating in hiring practices. Entered into 2 consent decrees Mayor essentially bargains away the prospective hiring methods (to enact affirmative action) in order to save the city a lot of money in back pay claims. White firefighters move to intervene prior to judicial approval of the claim, and court denies the motion because it was not timely. 2d Lawsuit: Enjoin implementation of the consent decreejudge refused. Court dismisses it by saying that if these guys are affected by the consent decrees, they could file a lawsuit under Title VII later, after they suffer the harm. 3d Lawsuit: The second group of white firefighters. The problem in the affirmative action plan turned out to be promotions: said blacks should be promoted on an equal level and no one less qualified should be promoted over someone more qualified. Wilks’ theory in the 3d lawsuit: Title VII. Wilks contended that he is not being promoted

because of his race; the fact that he is white means he receives disparate treatment. But disparate treatment claims require that you prove intent. The city gives, as a defense, that they are just complying with the terms of the consent decree, meaning they haven’t formed the intent necessary to uphold a disparate treatment case. 5 Source: http://www.doksinet Wilks responds to that defense by saying that he cannot be bound by that consent decree because he wasn’t a party to it. The key question is whether Wilks is rightis he being bound by the consent decree, or is he just being practically affected by it? The majority believes that under the “impermissible collateral attack” doctrine, Wilks would be bound by the consent decree, and it is impermissible to bind a non-party. The plaintiff, the initial architect of the lawsuit, has to structure the suit in such a way that all parties interested are joined in the initial suit, otherwise you run the risk that someone on down the

line will reopen the suit. Court says there is never a duty to intervene The burden of joining parties is on the current parties to structure the suit to avoid these kinds of problems. The court kind of expresses a preference for Rule 19 over Rule 24. What about the Eldredge case (above)? This case suggests all those male apprentices were necessary parties because they could later essentially reopen the judgment later by filing a Title VII suit. Stevens (author of dissent) doesn’t disagree with the majority on the duty to intervene business, but he is just saying that the white firefighters weren’t legally bound by the prior suit; they just had substantive rights affected. If they were legally bound, then they couldn’t bring a lawsuit under Title VII later on, because it’d be barred by preclusion. The effect of the consent decree gave the city a valid defense to the charge of the white firefighters they were being discriminated against. The decree is the substantive defense

against the white firefighters The only issues open for trial are whether the city really was using the consent decree when they did not promote Wilks, or if they were just using it as a pretext. Stevens says Wilks could prove that the consent decree was a fraud. If Wilks could show that the parties to the consent decree were colluding to deprive outsiders of their rights, then the consent decree would be thrown out. In other words, they could attack the consent decree, but only on very limited grounds. The problem, according to Rehnquist, is the nature of the remedy sought. In order to remedy past discrimination, they must put into effect an aggressive affirmative action program. That inherently affects others, many of whom are not at all the ones who were guilty of committing the discrimination to begin with. If in fact the city is responsible for the discrimination, then maybe the city has to enact an affirmative action policy to remedy that. But then if Wilks doesn’t get promoted

because of that policy, then perhaps the city would have to pay Wilks backpay because of that discrimination. Thus, it sets the city up for multiple liability The implications of the case: (1) Is it constitutionally-based? No. The court couches the decision in terms of the FRCP and the interaction between Rules 19 and 24. The scheme of the Rules is to place on the current parties through Rule 19 the duty to join all necessary parties. (2) Congress came back the year after this case and passed an Amendment to Title VII that was meant to overrule Wilks, but it applies only in employment discrimination. See page 99 Amendment says a party cannot challenge an employment practice that is the result of a litigated or consent judgment if they had notice of the litigation or if there was someone representing their interests in the suit. a. Is it fair to bind people in this way? What about the “falling constitutional ceiling” business? As a procedural matter, should the binding effect of the

judgment of a case be affected by later changes in the law? The law changed: The court used to be far more accepting of affirmative action plans than it is now. The court is more strict about what plan violate equality themselves. Does this mean we should not treat as final the judgments entered under the prior state of the law? FEDERAL JURISDICTION Two main types of federal cases: federal question (75% of federal docket) & diversity (25%) Congress created the lower courts immediately but did not confer federal question jurisdiction in the lower courts until 1875 when the multitude of post-war state legislation arose, and the federal government no longer trusted the state courts, in the wake of such rampant post-war discrimination, to make the decisions on federal questions. 6 Source: http://www.doksinet Three policy justifications for having federal question jurisdiction: (1) Uniformity. The federal law shouldn’t mean one thing in Mississippi and another in New York (2)

Expertise. Federal judges will develop an expertise in federal law (3) Hostility to federal rights. In an 1824 case (Osbourne), Chief Justice Marshall interpreted the arising under language to mean that the federal court would have power as long as the federal issue was an ingredient anywhere in the case. This defines what the Supreme Court can take by way of review. Congress drafts § 1331 when they confer federal question jurisdiction to the lower courts, and they use the same language: “arising under” the federal law, constitution and treaties. Even though the language is the same, the § 1331 language has been read much more narrowly than the “arising under” language of the Constitution. This means the cases that can be started in federal district court are a narrower class of cases than what can potentially be heard by the Supreme Court by way of review. How is it narrower? Some rules have been read into the statute. (1) Well-pleaded complaint rule of Mottley: in order to

invoke federal question jurisdiction at district court level, the federal issue has to be part of Plaintiff’s claim as revealed by the well-pleaded complaint. It cannot come up solely by way of defense. (2) “The creation test” promulgated by Oliver Wendell Holmes: if federal law creates the right to sue and the remedy, then federal question jurisdiction exists. The hard cases are when the federal issue is a statecreated right incorporating a federal element Plaintiffs would rather be in State court, and defendants would rather be in Federal court. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v Thompson (1986): Smith says that when a state-created claim requires a decision about whether or not a federal statute is constitutional, there is federal question jurisdiction. In Smith, the corp defendant bought federal bonds issued pursuant to federal statute that was charged as unconstitutional. Whether the corporate fiduciary violated his duty under state law depended on whether the bonds were

good, which turned on whether the statute creating them was constitutional. Moore: The state law said there was no assumption of risk if the employer violated a federal safety standard by its conduct. The court had to determine whether an employer violated a federal safety standard in order to determine whether an employer had a defense to a state-created negligence claim. No federal jurisdiction Did Merrell Dow resolve the tension between these two cases? Home Court Advantage. Note Δ cannot remove to federal court based on diversity, because of the home court advantage. If you sue the Δ in his home-state court, then Δ cannot complain about out of state bias, and therefore cannot remove. Facts & Background. π allege Δ was negligent because they did not comply with federal labelling requirements Δs removed on FQJ grounds and then argued for forum non conveniens dismissal. Court with proper jurisdiction can dismiss the case if there’s an alternative forum that is much

more convenient. The federal district judge dismissed on those grounds and instructed πs to go back to Canada and Scotland. πs appeal Appellate court reversed, but for the wrong reason. 6th Cir said that πs case did not invoke FQJ because it did not necessarily depend on the federal issue because that count was only one amongst 6 counts, and it’s possible to prove negligence without the federal element. BOTH SUPREME COURT majority & dissent reject the circuit court’s reasoning! Majority Holding: A complaint alleging violation of federal statute as element of a state cause of action does not arise under federal law under § 1331 when Congress has determined that there should be no private federal cause of action for the violation of that statute. If Congress hasn’t created the right for private parties to sue under the statute, then that means private parties shouldn’t be able to sue on a state law theory and get into federal court via FQJ. Smith involved the

constitutionality of a federal statute. Moore involved borrowing a federal statute for use in a state-law claim. We aren’t quite so concerned with whether a state court misinterprets a federal safety statute, but we are worried that the federal interest at stake in Smith, which is the possible declaration by a state court that a federal statute was unconstitutional. Merrell Dow is akin to Moore Therefore, because there was no FQJ in Moore, there is no FQJ in Merrell Dow. The majority says the reason we know the federal interest is not substantial is that Congress did not create the right to sue. 7 Source: http://www.doksinet Commentators have read into this the notion that this is another rule being read into § 1331: where states create the cause of action, falling outside the Holmes creation test, and it incorporates the federal element, then it must be determined whether the federal interest is substantial. It will be substantial if it involves determining the

constitutionality of a federal statute (Smith) but is not substantial if it is just borrowing the federal safety statute for a state claim (Moore). Dissent: Dislikes the substantiality test, because it’s too vague. It’s a post hoc judgment as to what’s substantial Smith & Moore cannot be reconciled. A vague test like substantiality allows anything to be reconciled Smith should be applied and there should be FQJ. Diversity Jurisdiction § 1332: Two Requirements (1) Complete diversity (everyone lined up as π must be from different state as everyone lined up as Δ) (2) Amount in Controversy = $75,000 To figure out where people are from for diversity purposes: Individuals = state of domicile (presence + intent to remain indefinitely) Corporations = state of incorporation and their principal place of business To get to the amount minimum, you cannot aggregate claims among co-parties. (One party can aggregate his own claims, but multiple parties cannot pool theirs together.)

Supplemental Jurisdiction § 1367 If there is an anchor claim that got you to federal court through diversity or FQJ, then you can bring with that anchor claim to federal court all other claims connected to it through a common nucleus of operative fact. CNOF Test (Gibbs): Means same thing as the “transaction test” from the joinder rules. You’re looking for factual connections between the two claims, such as overlapping evidence, overlapping issues, whether or not res judicata would prevent π from splitting the claims, and a logical relation between claims. Where the anchor claim is a federal question, then the supplemental claims will also have FQJ. But if the anchor claim is a diversity claim, § 1367(b) forbids claims by plaintiffs when doing so is inconsistent with the requirements of the diversity statute. Circuits split on whether there is supplemental jurisdiction over the claims of class members that are not individually worth more than the diversity minimum. The question

on which they are split is: Can you use the diversity statute to get the anchor claim in (which has a claim of over $75,000) and then use supplemental jurisdiction to get the other claims, which do not individually meet the minimum amount, in to federal court as well? With class actions, the way you figure out diversity jurisdiction is to look at the state of the named representative. Only the named representative must be from a different state as the defendant. That goes back to a 1928 case and is the traditional rule. With the amount in controversy, though, there’s a case called Zahn decided in the 70s, which said the claims of each class member have to exceed the jurisdictional minimum to meet diversity jurisdiction. Note they’ve kind of divided up the requirements on one hand, only the named plaintiff need be “diverse,” yet each individual claimant must meet the minimum amount. In the Class Action Fairness Act, which was filibustered last term, the requirement would be only

minimal diversity, meaning that as long as any plaintiff was diverse from any defendant, the case could be removed to federal court. Because nearly all defendants want to be in federal court, this would basically federalize mass suits Abbott Laboratories: Plaintiffs trying to keep their claim in State court. Δs remove the case and πs petition for a remand back to state court. Note federal court decides whether or not to remand without certifying the class; it treats it as a putitive class. A potential statutory problem: Removal statutes say when a federal court remands a case to state court for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, there is no appeal of that. Fifth Circ says remand was based on abstention (the Colorado River case) rather than on SMJ and therefore the bar for appeal does not apply. Jurisdictional Issue: State anti-trust statute that created the action provides for trebel damages, which would be about $20,000 per plaintiff. At the time, $50,000 was the jurisdictional

minimum So it looks like, as to actual damages, none of the class members met the minimum. Defendants say, though, that in Louisiana the Code says a class representative is entitled to attorney’s fees, which would be way more than $30,000, rendering it above the minimum amount. Plaintiffs, on the other hand, argue that is money that the Plaintiffs will never see, 8 Source: http://www.doksinet never get a part of, and therefore should be treated as pro-rated amongst all the class members. Doing it that way leaves all the class members below the jurisdictional minimum. The 5th Cir. says under the plain language, the attorney’s fees money goes to the named representative The effect of that is to attribute the attorney fees recovery to the named representative which puts them over $50,000. That means the named representatives have claims that meet the diversity requirements and are therefore properly in federal court. This has been a similar problem with punitive damages, which

aren’t meant to compensate any one person in particular but meant to punish someoneso who do those damages get attributed to, or do they get prorated among class members? Many states have laws dictating who the punitives get attributed to. So what about the unnamed class members? They do not meet the amount in controversy requirement, so they cannot get to federal court on diversity jurisdiction. Can they get there on supplemental jurisdiction? § 1367(a) creates a rule that all claims connected by a common nucleus of operative fact to the anchor claim are within the court’s jurisdiction. If you have a federal question anywhere in the case, then all other claims connected by a CNOF are automatically within the court’s jurisdiction. § 1367(b) carves out an exception to the rule established in (a) which only applies in diversity cases. The exception does not list Rule 23, which is the class action rule, as one to which the exception applies. Zahn said the claims of each class

member have to be worth more than the jurisdictional minimum, BUT the supplemental jurisdiction statute appears to create jurisdiction over claims connected by a CNOF, and apparently the (b) subsection does not apply. So here’s the deal: Do you read the plain language of the statute to overrule Zahn, or do you listen to the drafters of the statute that say directly they meant to preserve Zahn even though they forgot to put Rule 23 in the statute? Of course, the circuits are split. The 4th, 5th, 7th and 9th Circuits all believe that because there’s no ambiguity or absurdity in the plain language of the statute, they cannot look beyond the plain language. This has the effect of sending more class actions to federal court. [The Supreme Court has taken Cert on this so we’ll have a decision by the end of the term.] § 1367(c) uses the word “may”, unlike (a) and (b) which use “shall.” Thus, (c) creates discretion in the federal district court to decline to exercise supplemental

jurisdiction if one of the listed factors is true. You can tell from the opinion that courts don’t treat the discretionary space very broadly. There has to be a good reason for them to not exercise supplemental jurisdiction. The 5th Cir. said the lower court abused discretion by not taking the case because it would result in piecemeal litigation. In general when federal courts have jurisdiction they have an obligation to exercise it. So when either FQJ or diversity jurisdiction or supplemental jurisdiction there is a “virtually unflagging obligation” to exercise it. The Supreme Court can do that, but none of the lower courts. But there are some exceptions: the abstention doctrines. But those doctrines require a really good reason for abstention! Basically, the court in Abbott is saying the district court doesn’t have a good reason not to decide the named representative’s claims, and if you can’t decline the named representative’s claims, you cannot use the discretion

under (c) to refuse to hear the absent members’ claims either. JUSTICIABILITY & STANDING Standing, ripeness & mootness are functions of the “case and controversy” requirement from Article III, § 2. Why did the constitutional framers want to make sure the federal courts would hear only live cases and controversies? Separation of powers. We don’t want courts to make opinion proclamations or advisory opinions. That means these standing issues tend to be a problem more in public law cases, like where a bystander wants to affect government behavior. (In the normal tort case it’s an injured party bringing a claim so standing isn’t usually very tough to figure out.) The idea is the plaintiff must show a direct injury, not just a general interest that would be shared with all other members of the public, and must have a personal stake in the outcome of the case. Otherwise the courts would become just another political branch This interest does not have be economic.

Standing Three-Part Test: Plaintiff bears the burden of proof to demonstrate: (1) Injury in fact. a. Concrete 9 Source: http://www.doksinet b. Particularized c. Imminent (not speculative) (2) Causation: injury identified in (1) must be fairly traceable to the conduct of the defendant (3) Redressability. Must be likely that the injury would be redressed by the relief sought in the lawsuit (A plaintiff must show standing as to each form of relief sought.) Organizational Standing: When can an organization have standing to bring a lawsuit? (1) Members would otherwise have standing in their own right (2) Organization is asserting interests germane to its own purpose (3) No need for individual parties / members to participate. Prudential Considerations (1) Zone of interest. The plaintiffs must be in the zone of interest meant to be helped under the law (2) No Generalized Grievances. Court won’t hear general grievances shared by large classes of citizens (3) No third-party standing.

Plaintiff must usually assert its own legal interest rather than those of third parties Friends of the Earth, Inc. v Laidlaw: Plaintiffs are FoE, who are joined with the Sierra Club. They’re arguing Δs dumping mercury into water πs representing interests of those who use that water area for recreational purposes. Suing under the Clean Water Act. Defendants’ strategy: Get state to file preemptive lawsuit. What did they do to fight the ongoing FoE lawsuit? Said they had no standing to bring it and were barred by the other suit being filed first. Judge: Denied motion to deny based on standing. Not barred by first lawsuit because that one was collusive, not diligently prosecuted. What relief is ultimately ordered in the district court? No injunction, just civil penalties. The deterrent effect of the civil penalty, which is paid to the government, plus the attorneys fees Laidlaw had to pay πs, was enough to avoid needing an injunction. Note that the violations continued after the

filing of the suit but by the end of the district court case Laidlaw had come into substantial compliance. On appeal of the civil penalty it goes to the circuit court. At Supreme Court level let’s check the standing. Injury In Fact. Problem is district court found despite the numerous permit violations there was no actual injury to the environment. But the majority says it is not the test of whether the environment was injured but whether the plaintiff was injured. The plaintiffs claimed they would go camping, fishing, etc if the mercury was not being dumped there. Causation. Not a problem if you buy into the injury in fact claimed Redressability. An injunction would redress their issue But how does a civil penalty paid to the government redress their injury? The majority view is that the civil penalty has a deterrent effect on the violator. Relationship between Standing & Mootness. Three differences between standing & mootness: (1) burden of proof on standing is on πs, but

for mootness the burden is on Δs; (2) there is an exception to the mootness doctrine for actions capable of repetition yet evading review, but no such exception exists for standing; (3) policy: with standing, part of what you’re worried about is needing a concrete dispute warranting the expenditure of federal judicial resources, but with mootness, typically a lot of federal resources have already been usedthis is the “sunk cost” problem, the idea being the court will be hesitate to dismiss a case for mootness once it has a bunch of time and money invested in it. Ripeness Usually works that government has passed a law and a citizen believes it’s unconstitutional, but the law hasn’t been enforced against him yet. For example, you want to run an adult bookstore and your local zoning authority passes an ordinance saying that you cannot run an adult bookstore. The strategic dilemma for you is that if you sue to have that ordinance declared unconstitutional, the court may say

it’s not ripe yet because it hasn’t been enforced. But if you open your store and wait to be prosecuted, then if you try to file a federal lawsuit, you’ll run into an abstention doctrine that the federal government won’t interfere with the criminal state proceedings. Of course, that’s only a strategic dilemma if you want to have access to the federal forum on the issue of whether or not the state ordinance is constitutionalif you don’t mind being in state court then you just wait to be prosecuted and bring it up as part of your defense. 10 Source: http://www.doksinet Test for Determining Whether a Pre-Enforcement Constitutional Challenge is Ripe: (1) Likelihood that the disobedience will occur (2) Certainty that the disobedience will take a particular form. The idea is that we want a concrete, definite dispute, to avoid making the court discuss hypothetical abstracts. (3) Any present injury caused by the prospective enforcement. (4) Likelihood that the enforcement will

actually happen. There would be a difference, for example, between a law that had been on the books 100 years ago without ever being used and a brand new law just passed. Also: whether issue is fit for judicial resolution, and whether there would be hardship to the parties if they had to wait. San Francisco Voters v. Supreme Court: Voters want to be able to put their names in political pamphlets as endorsing a particular candidate, and the CA constitution says that a party cannot endorse a candidate for a non-partisan election, and that all city, county, judicial and school elections are non-partisan. The plaintiffs are individual voters, some of whom are also members of Republic and Democratic committees. Note that neither the Committees themselves nor the candidates are the plaintiffs. The defendants are the city employees who redacted the names / endorsements from the pamphlets. Plaintiffs argued that their ability to hear information about whether parties had endorsed particular

candidates is chilled because of this redaction. Court initially notes standing problems: (1) 3d party standing: the plaintiffs here are asserting the rights of the candidates to include endorsements rather than the candidates themselves asserting that right. On the other hand, it may be direct if there is indeed a right to receive information rather than just a right to give it. (2) Redressability. CA also has a statute that basically says the same thing as the state constitution So even if the case is successful and the constitutional provision is declared unconstitutional, it will still be possible for the redactions to continue because of that state statute. (3) 3d party standing again. These plaintiffs don’t have standing to assert the rights of the committees Court says there is no current live dispute. The future elections are too iffy The elections that are over are moot What about the exception: capable of repetition yet evading review? Why doesn’t that work? The

plaintiffs waited until the elections were over before they filed suit. That exception does not revive a case that was moot at the moment the case was filed. Plaintiffs failed to allege that there was any current infringement on their rights. Court says that postponement of the suit would not create hardship to anyone. Stevens’ concurrence said that the case would be ripe if it were brought by the candidate or committee. Then we get to the dispute between White, Marshall and Blackmun. White wants to treat it as an as-applied challenge, and Marshall & Blackmun see it as an overbreadth problem. If π’s complaint can be seen as a challenge to the face of the provision, then it may survive the problem of “future elections being too hypothetical.” Political Question Doctrine If you break down the six factors from Baker, they work out to be three basic concerns: (1) Constitutional. Captured by the Nixon language that if there’s a demonstrable textual commitment to another

branch of government, the court shouldn’t hear it. (2) Functional. Courts can only deal with cases that are concrete and where there is some sort of clear standard by which to decide it. (3) Prudential. Respect for the other branches of government and the separation of powers There is nothing in the constitution that says courts cannot hear political questions. So from where does their power to refuse those questions? The structure of the constitution. It’s also weird because we know there’s judicial review of Congressional actions, so it cannot be the case that whatever task is delegated to another branch of government is “off-limits.” Nixon v. Supreme Court of the US: Federal judge convicted of accepting gratuity. Refuses to give up his judgeship He is impeached, meaning House presented articles of impeachment and the Senate then has the sole authority to try the case. Senate appoints the committee to assemble and hear the evidence, and then it is presented to the whole

Senate who votes to convict. 11 Source: http://www.doksinet Nixon files suit saying his right to be tried by the Senate was not carried out because the whole Senate did not hear his evidence. The issue is whether this is a justiciable question in the federal courts given that the constitution confers sole authority to the Senate to try impeachment cases. Court focuses on constitution’s use of the word sole. Court focuses on the constitutional language Dissenters say the word gets taken out of context; that the purpose of the word sole is to clearly divide the charging function, which goes to the House, from the trying function, which goes to the Senate. DISPOSITION OF DUPLICATIVE OR RELATED LITIGATION Repetitive Form 1: π v. Δ things don’t go well for π, so he goes to another forum and refiles Reactive: Forum 1: π v. Δ Forum 2: Δ or X v. π Overlapping Class Action: π1 v. Δ π2 v. Δ etc. Three basic methods to commandeer litigation into the court of your choice: (1)

Stay / Abstention. Go to the court where you don’t want things to continue, and ask for a stay In the case of federal / state litigation, you can ask the feds for an abstention. (2) Injunction. Addressed to the court where you do want things to continue Ask for an injunction to stop the case from proceeding in the other court. Of course, courts don’t really like to enjoin each other, but you can get injunctions against the parties. If it’s federal / federal, it’s just the injunctive standard If it’s federal / state, you’ll have to overcome the injunction act. (3) Transfer / Consolidation. Directed to court where you don’t want things to continue Consolidation Rule 42 requiring a common issue of law or fact. The cases must be pending in the same federal district in order to be consolidated. In order to get them into the same federal district, you transfer We’ll talk about three transfer statutes: general §1404, 1406, and multi-district litigation § 1407. Notice that in

addition to figuring out which tool you’ll use, you have to make sure you choose which court you’re going to address it toyou must be careful to address it to the court that will be the most responsive. Because the “first in time rule” is not an absolute, not all judges will use it in the same way. Federal / Federal Dual Pending Cases: Gluckin v. Playtex (2d Cir 1969): Playtex is upset because they say their bra patent is being infringed by Gluckin, who was manufacturing bras for sale at Woolworth. So they sue Woolworth for selling the allegedly-infringing bra Strategy 1: Why go after the retailer when your real beef is with the manufacturer? If you can cut off your competitor’s market then you get a win without having to deal directly with the competitor on whether or not they’re actually infringing. Woolworth is likely to just settle and stop selling the infringing bra, since they don’t care about whether Gluckin stays in business. Strategy 2: Playtex sues in Georgia

even though they are located in NY and the manufacturing is happening in NY. Playtex had three of its mills in GA and the jury pool there, because they wanted to keep those jobs in GA, would be more favorable to Playtex. This is reactive litigation: Playtex v. Woolworth in GA, and then reactive is Gluckin v Playtex in NY Gluckin asks the NY court to enjoin the GA court. The issue on appeal was whether the NY court properly issued the injunction against the GA court. The general rule is First in Time Rulethe case filed first is usually the one that gets to go forward. Exceptions: (1) Customer Suit Exception. If the first-filed suit is by the patent-holder vs retailer, and the second suit is patent-holder vs. manufacturer, the 2d suit is the real one and should go forward (2) Blatant Forum Shopping. 12 Source: http://www.doksinet What other options would Woolworth or Gluckin have had? All the reasons the court gives for reasons to grant the injunction would also be a great argument

for transferring to NY. Could also make a 12(b)(7) motion to get Gluckin involved in the litigation. Semmes Motors, Inc. v Ford Motor Co (1970): Suit 1: Semmes v. Ford in NJ state court, which is removed to federal Suit 2: Semmes v. Ford in NY where judge issues injunction Ford then terminates Semmes’ license as a Ford dealership. Ford goes ahead and files an Answer and Counterclaim in the NJ suit. This is important b/c if they hadn’t filed that Countersuit, Semmes could have voluntarily dismissed their lawsuit in NJ. Once that counterclaim is filed, Semmes cannot unilaterally dismiss that whole lawsuit. TRANSFER STATUTES § 1404(a) Case may be transferred from federal district to federal district, to a place where it could have been brought. This means the transferee district must be one where π could have filed originally. It must therefore have proper personal jurisdiction and venue. Even though Δ can waive objection to personal jurisdiction, they cannot move to transfer to

somewhere where they would have had to waive objection because the π couldn’t have actually filed there. The standard is, for the convenience of the parties (private and public interest) and in the interests of justice. This is supposed to embrace the same standard as the common law notion of forum non conveniens. Private interests include where the parties and evidence are located, whether witnesses will be available, how easy it is to litigate there. Public interests include how difficult the choice of law issues will be, whether there is enough of a connection to justify imposing jury duty on the local community, etc. How does the common law fit with the statute? The statute supercedes the common law whenever the alternative forum is another federal district within the United States. Thus, all that’s left of the common law doctrine are those situations where the alternative forums are outside the U.S In order to bring a motion for forum non conveniens, you must first show that

there is an adequate alternative forum outside the country. Then you must look at the private interest factors and the public interest factors, and it is a very ad hoc, discretionary decision. Both the statute and common law doctrine are highly discretionary. You use § 1404 when the transferor court has proper venue. The question is whether there is another place that also has proper venue where litigation would be more convenient. When a case is transferred under § 1404, transferor law applies. That is, even after it is transferred, the law of the place that transferred it applies. That is true even when the transfer is initiated by the plaintiff § 1406 A federal district court that lacks proper venue can either dismiss the case or, if it be in the interests of justice, can transfer to a federal district that would have proper venue. In an old case (Goldlawr), the Supreme Court interpreted this to mean that if the transferor forum lacks personal jurisdiction, it could transfer.

This is odd, because the case says that a court that lacks power over a party can transfer the case to somewhere that does have power. The big difference between transferring under 1404 and 1406: Under § 1406, the transferee law applies. What if court has proper venue but lacks personal jurisdiction? Which statute should apply then? Perhaps if the initial-filed place lacks personal jurisdiction, you shouldn’t be able to lock in that place’s law by transferring under § 1404. § 1407 Ginsey Industries, Inc. v ITK Plastics, Inc: There are two different transactions here, unlike Semmes Still dismissed, though, with the possibility of consolidation weighing heavily in favor of transfer. De Melo v. Lederle Laboratories (1986): Brazilian π files suit in MN (where her attorney lived & where Δ company was licensed to do business). Δ moves to remove to Brazil. District judge dismissed on forum non conveniens 13 Source: http://www.doksinet Appellate court draws on Supreme Court

precedent in ruling that just because the alternative forum is less favorable to Plaintiff, the alternative isn’t necessarily an inadequate forum. Multidistrict Litigation Act: Permits cases that share a common factual issue to be consolidated to one federal district for pretrial procedure. Should you read the MLA to mean we want to coordinate discovery, or should it be about everything that happens pretrial including all the dispositive motions? That is the intellectual debate. Multidistrict Litigation Panel: There’s a panel of 7 judges, no two of which are from the same circuit. These are judges who also have duties in their own courts, appointed by the Chief Justice. They have a clerk in Washington, D.C, where papers are filed Panel will only hold a hearing if there are objections to the transfer If they hold hearings, they do so at various places around the country, and will appoint spokespersons for both sides. The vast majority of cases referred to the panel wind up getting

transferred. The panel must answer (1) whether to transfer (common question of fact) and (2) where (or to whom) to transfer. Once they decide a piece of litigation should be sent to a particular place, then any other cases filed anywhere else in the country are automatically transferred to that district and are called “tag along” cases. There is no appellate review of the decision not to transfer. It is possible to get the review for the decision to transfer by applying for a Writ of Mandamus to the court that oversees the transferee court. Cases are supposed to go back to their home districts for trial. But statistically, fewer than 5% ever do Why? Most cases settle before trial. Summary judgment takes a lot of cases out before trial. The MDL Judge frequently would transfer the cases to himself under § 1404 for trial. The Supreme Court struck down that practice in the Lexecon case in 1998 because the Statute says the cases shall be remanded to their home districts for trial; it

is not discretionary on the part of the judge. A bill passed the House last year (2004) to reverse Lexecon and allow an MDL judge to transfer cases to himself. But there is no companion bill pending in the Senate. Meanwhile, the panel sent a memo to the MDL judges saying they could accomplish this in other ways: Get parties to consent to dismissal in their home districts and refilling in the other district. Form a class. It’d have to be a mandatory class Try a “bellweather” casepick one case and try it in the home district and then let the other cases decide whether they want to litigate there. Get the home court judges to transfer the cases. In re Factor VIII or IX Concentrate Blood Products Litigation (ND Ill. 1996): Δ wants 137 experts which, for πs, makes it difficult because of the financial outlay that would require. FRCP Rule 16: (Specifically subsection c, e) Discussing pre-trial conferences. The Choice of Law Problem under § 1407 & Multidistrict Litigation: Law of

the transferor court must apply if the parties are in federal court only on diversity. If it is a federal question case, and it gets transferred under MDL, there is a split in the circuits as to what to do when there’s a split in the circuits! Federal/State Transfers Abstention: Set of common law doctrines. SC said it is a “general framework” of the federal court being sensitive to the state court-federal court relations. Four Types of Abstention Doctrines: (1) Pullman a. Used when a federal court is dealing with a case where (1) there is an uncertain or ambiguous, unsettled issue of state law, and (2) when that ambiguity is cleared up, the federal constitutional issue may go away, thereby avoiding an unnecessary federal constitutional decision. 14 Source: http://www.doksinet b. c. d. e. f. g. h. i. This might be applied when (1) there is an uncertain or ambiguous, unsettled issue of state law, and (2) a very important state interest at stake. Eg, an eminent domain case

that implicates an unclear issue of state law. This is a species of the Con Law issue that courts will avoid making constitutional holdings if they are at all able. This is a stay, rather than a dismissal, so that the parties can go to state court and get the ambiguity cleared up, and then return to federal court if the live issue still exists. If you use Pullman, typically it’ll be a situation where someone’s come to federal court and said “This state practice is unconstitutional” but there’s something unclear about the state law and it’s possible that the state could interpret its law that avoids the constitutional question. So the idea is to take the case to state court and clear up the ambiguity. If it turns out there really still is some unclear part of state law, the parties can come back to federal court. England ReservationEssentially removes the res judicata bar to returning to federal court. You’re reserving your right to return to the federal forum after the

ambiguity has been cleared up by the state court. i. There is a rule that plaintiffs must bring all their claims that arise out of a single occurrence in one lawsuit, and if they do not, then they lose the right to bring those claims. You cannot “split” claims If there’s been a Pullman abstention at a federal level, then the parties have to litigate in state court, and traditional rules would then dictate that was the parties’ “bite at the apple” and wouldn’t give them another bite at it in the federal forum later. ii. This allows the parties to litigate state issues in state court, and federal issues in federal court. iii. HOWEVER, even though claim preclusion won’t be a factor, issue preclusion may kick in. Whatever fact issues are decided at the state court level and are also relevant to the federal claim will be given preclusive effect at the federal court. Certification. Many states (but not all) have a statute that allows federal courts to certify questions

typically to the state supreme court to clear up any ambiguity, and that procedure is preferable because it does not require a formal stay of the federal case, and you don’t have to start all over in the state trial system. This is supposed to be a more efficient procedure, but in reality, there is still usually a considerable delay. The problem of exclusive federal jurisdiction. What if the unclear state law issue arises relative to the federal anti-trust law, or another law exclusively within the purview of the federal courts? Should the federal court abstain if it has exclusive jurisdiction? i. Depends on what you think exclusive jurisdiction is for If you think it’s just for getting the expertise of a federal judge in applying federal law, then waiting for the state court to render a decision is not a problem. But if it’s to have a federal forum for the whole caseincluding the fact-finding, then it would be problem, because of the issue preclusion. ii. Courts have said that

there should be no abstention where the federal court has exclusive jurisdiction. EXCEPTIONS: i. Time is of the essence This demonstrates that the Pullman abstention is discretionary If it were mandatory, then time wouldn’t matter. ii. State court procedures are clearly inadequate (2) Burford a. Typically a dismissal of a case by a federal court when the federal court declines to act so as to avoid interfering with a complex state regulatory scheme. b. Burford dismissal will happen when the federal relief sought is injunctive If the plaintiff in federal court is seeking damages, then there is no Burford dismissal. Issuing an injunction is more of an interference by the feds into state schemes than the feds just handing down a damage award. c. Certain subjects are peculiarly within the province of a state: controlling oil & gas leases, eminent domain, schools, etc. The idea is that we don’t want the federal courts enjoining the states in a way that undermines their regulatory

scheme. The court isn’t just “staying its hand” to see what the court will do as with Pullman; with Burford, the court is staying out of it entirely. 15 Source: http://www.doksinet d. e. f. Burford was a case dealing with who gets to control the leases for drilling for oil and gas. The suit was because they were mad at the commission for giving a lease to their competitors. If the federal court were to grant an injunction telling the state commission that they have to give a lease to the plaintiff, that would undermine the state scheme for deciding who gets leases and when. Argument as to whether Burford should ever be invoked if there is a federal question implicated, and the consensus is that Burford should be invoked when it’s of important interest to the state, there is a complex regulatory scheme, and the conflict cannot be resolved without the federal court immersing itself in the state scheme. Burford is rare. (3) Younger (equitable) a. Bar to federal court

interference with ongoing state proceedings Look for a pending state proceeding where the state is a party or the state has an important interest at stake (usually the state’s interesting the integrity of its own procedures, esp. enforcement) b. Federalism Used when the federal court abstains in deference to states’ criminal, quasi-criminal (e.g, zoningadult bookstore), civil cases in which the state itself is a party, or purely private state cases with an important state interest involved (e.g, enforcement proceedings (see (f), below). We don’t want feds poking their nose into state affairs, particularly state criminal affairs c. The idea: Probably every criminal Δ thinks the state, at some point in the process, violates his rights, be in at arrest, search and seizure, etc. You cannot have a situation where every state criminal Δ files a federal lawsuit at the same time their state case is going on because it would cripple the system. d. When there is an ongoing state criminal

proceeding, a federal court will not interfere; instead, the person aggrieved (the criminal Δ) should raise their federal constitutional claims in the state proceedings. e. The Younger doctrine insulates the ongoing state criminal process from any federal review except for the Supreme Court. f. Younger has been expanded beyond criminal proceedings to also apply to: i. Quasi-Criminal Zoning, for instance, where an adult bookstore comes to town in violation of a zoning ordinance, and the owner is prosecuted. ii. Enforcement of Contempt Feds should abstain, forcing the parties to litigate the federal claims about the procedure in the contempt proceedings. g. EXCEPTIONS: i. If the state has acted in bad faith to harass someone State keeps bringing the charges and then dropping them so as to bother you without ever giving you your day in court. ii. If the state statute involved is flagrantly unconstitutional iii. If there are unusual circumstances such that the state decisionmaker was

obviously biased. h. The idea is that courts of equity won’t act when there is an adequate remedy at law That is, there is an adequate remedy at law available through the state system. We don’t want the courts issuing injunctions (equity), but what about damages? That’s an unresolved issue: whether a federal court in a case seeking damages must abstain in deference to an ongoing state proceeding. Many lower courts have said that the federal proceedings should be stayed until the state proceedings are completed. i. TIMING: STEFFEL GAP Younger is not applicable unless there is pending state proceedings, meaning if there is no pending state proceeding yet, a litigant may seek an injunction and/or declaratory relief in federal court. If you think you’re going to be prosecuted under an unconstitutional state ordinance and you want to sue for a declaration that it’s unconstitutional and an injunction to stop them from prosecuting you, you have to wait until it’s ripeuntil

imminent or actual prosecution. But then if you wait for the prosecution to commence, you’re in Younger territory. So the Steffel Gap is when the state prosecution is imminent but has not yet actually started. i. You want to run an adult bookstore and the state passes an ordinance to prevent that from happening. You go to federal court before they actually do prosecute you and file a case that it violates your rights under the constitution. The next day the DA files charges against you in state court. Younger or no? 16 Source: http://www.doksinet 1. 2. Fed court must abstain under Younger unless it has already begun proceedings with substance. So you have to try to get an injunction (showing likelihood of success on the merits and that substantial harm will occur in the absence of the injunction) before the state files its case. OR you avoid doing the thing that will put you in violation of the state law (opening the adult bookstore, for instance) until your federal case is

complete. (4) Colorado River a. A stay in the exercise of wise judicial administration to avoid duplicative litigation b. On one hand, if the federal court has jurisdiction it has a “virtually unflagging obligation to exercise it.” On the other hand, the court wants to avoid piecemeal litigation and inconsistent results and should defer to state litigation to accomplish that. c. Has less to do with federalism than with efficiency concerns d. Supreme Court has not given us a clear test for this, but it has laid out factors: i. Order in which proceedings were filed ii. Whether there is any property over which either court has taken control (if it is an in rem case) iii. Which, if either, forum is more convenient iv. Avoiding piecemeal litigation v. If there is a federal question involved, that should weigh against abstention e. This is not a strict first-in-time rule; the court is to examine what has happened in each case thus far (has one court put in much more procedure and effort

than the other). f. In general it is okay to have parallel in personam proceedings going on in state and federal court, even between the same parties, and on the same topic. It must be exceptional circumstances in order to justify abstention. g. This becomes a race to judgment, as issue preclusion will kick in from one state to another So whatever court you’re doing well in is the court you’ll be trying to speed along to judgment (and, of course, your opponent will be trying to slow down the proceedings in that case). h. TWO CAVEATS TO COLORADO RIVER: i. If the federal case is a declaratory judgment action, the Supreme Court has said there is more discretion to abstain. ii. Exclusive federal jurisdiction issue what if there’s duplicative litigation but the federal jurisdiction is exclusive? The 9th Cir. said there is an absolute rule against the federal court abstaining under Colorado River if it has exclusive jurisdiction. If there is anything to discern from abstention, as

least as to the top 3 categories, it’s that there are times when the feds just shouldn’t be sticking their noses in the states’ business. Colorado River is more about process and efficiency. Court says these categories aren’t rigid “pigeonholes” but are more a tapestry of ideas. That means that your case doesn’t have to fit perfectly into any one of these categories; you can make some analogous arguments using them as a guide. The court is not to make this sort of argument sua sponte because by the time you get to abstention, you’ve already established that the federal court has subject matter jurisdiction, and the court isn’t otherwise supposed to “pick and choose” its cases to hear. The argument can be made that it is a violation of the Congressional conference of power on the courts to hear the cases when the cases choose to not exercise their jurisdiction. The flipside to that argument is federalism: the court is only abstaining in cases where the state is

doing something with it. BT Investment Managers, Inc. v Lewis: Pullman: Even if it is a state regulation that has never been interpreted, if there is no genuine ambiguity, then there is no reason to invoke a Pullman abstention. The possibility that a statute might be struck down under the state constitution does not warrant Pullman abstention. It doesn’t negate the need to invoke the federal forum Just because it’s possible the state might strike down a statute, that doesn’t warrant a Pullman abstention. 17 Source: http://www.doksinet Burford: There is a simple statutory provision at work; there is no “elaborate scheme.” The statute is clearly separable from the elaborate banking regulations of the state. Striking down this one statute will not undermine the rest of the banking scheme. Pennzoil Co. v Texaco Inc: Pennzoil (P) sued in Texas state court, P’s home turf, for tortious interference with contract. The jury came back with a huuuuuuge verdict in favor of P

against Texaco (T). So T files suit against P in New York federal court, T’s home turf, challenging the constitutionality of the Texas procedures. T claims Texas’ execution procedures violate the Constitution The Rooker-Feldman Doctrine. The lower federal courts may not be used as courts of appeals of state judgments There is a difference in this case, as an example, because T was not arguing that the verdict was wrong, but that the execution procedures violate the Constitution. It’s a different claim In Texas, you had to put up a bond to keep the judgment liens from going forward. In this case, the bond was so huge, T couldn’t even meet it. T argued that essentially its right to appeal in Texas is contingent on this bond, and they aren’t able to meet the bond, rendering them unable to appeal. The federal district judge in NY sides with Texaco and enjoins execution of the judgment. It comes up to the U.S Supreme Court, who decides to abstain, citing to Younger Prior to this

case in order to abstain per Younger there had to be an overriding state interest at stake, and the state was often a party. For the Court to decide there is a Younger abstention here, it has to find a state interest at stake. What was it? The state has an interest in the integrity of its court system and allowing its judgments to be enforced. So how far can you take this idea? Any time there’s a pending civil proceeding in state court, do the feds have to abstain? Because, after all, the states will always have an interest in their own proceedings. It’s probably more just that after the case has come to judgment, and their enforcement procedures are in jeopardy, does this notion come into effect. When the proceedings in state court are disciplinary in nature, and the target of the proceedings tries to go to federal court to challenge the disciplinary procedure, the feds will abstain. This is similar to quasi-criminal proceedings. It’s the situation where it’s private party

versus private party that gets confusing Life-Link International, Inc. v Lalla: Suit 1: State court, Lalla v. Life-Link Suit 2: Federal court, Life-Link v. Lalla (including Nena) No venue in the case if Nena was involved in Suit 1. We don’t know why Life-Link didn’t remove in Suit 1 You’re a Δ sued in your home state court where diversity exists. You cannot remove because you’re in your home state. But you really want to be in federal court, so you file a reactive suit against π in federal court Should the federal court abstain? NOThe attempt to remove is forum shopping, clearly, and the state action was filed first. To allow the federal case to go forward undermines the removal rule that prohibits home-state removal. Anti-Injunction Act Federal courts may not enjoin “state proceedings in a state court”. You cannot get around the AIA by enjoining the parties rather than the state courts directly, because that has the same effect. You cannot get around the AIA by just

issuing a declaratory judgment either, according to most lower courts. Court-ordered arbitration has been found to count by some lower courts. Three exceptions to the AIA: (1) As expressly authorized by an Act of Congress. a. Interpleader statute specifically says the federal court has the power to enjoin state actions that may interfere with the interpleader. Otherwise, the stakeholder would start the interpleader, and then an individual π could run off to state court and hope their claim got judgment first. b. Bankruptcy All of the debtors assets are put together in a pool and divided amongst all creditors All other proceedings involving any of those assets in any other court are stayed. c. § 1983 Because, by its terms, it is about the feds controlling the behavior of the state, it could not be effectuated unless you allowed the feds to enjoin state action. To give it its intended scope it is 18 Source: http://www.doksinet read to be an express authorization of injunctions

which therefore makes it an exception to the AIA. But here’s what is weird about ittry to put that together with Younger This, by definition, is a proceeding with state interest. This and Younger are inconsistent Even though §1983 is an express exception to the AIA you’d still have to come within an exception to Younger to get the federal court to issue an injunction. Younger is a separate constraint on what the federal court can do. d. FRCP 13(a) doesn’t count (that’s the compulsory counterclaim rule) That means π can sue Δ in federal court, and Δ can sue π in state court, and the federal court cannot enjoin the state action. So it becomes a race to judgment. (2) Where necessary in aid of its jurisdiction. a. Traditionally applied only where there is in rem jurisdiction, or something like it If federal court has taken power over a piece of property, it cannot have competing state judgments that would compete with that. i. People who want to get federal court injunctions

argue that your case is like an in rem case in that the court has invested so much in negotiating or bringing to judgment a complicated class action or multi-district litigation, that allowing a state case to continue and mess that up would be a huge problem and waste of resources. b. To effectuate removal π sues Δ in state court There are grounds for removal Δ removes to federal court. The state is to cease doing anything in that case, but if the state court keeps proceeding, the federal court can enjoin the state from proceeding. That doesn’t happen very often. (3) To protect or effectuate a federal court judgment. Standard Microsystems Corp. v Texas Instruments, Inc (1990): SMC π sued TI Δ in NY federal court. Obtained TRO against TI to preserve the status quo of their business relationship pending the outcome of the case. TRO granted on Friday TI sued SMC in Texas state court that following Monday. (Note these claims are clearly arising out of the same series of transactions

as the first case, so they’d be compulsory counterclaims in the first casebut there’s no rule that allows the feds to seize control of those.) SMC requests a preliminary injunction against the state court proceeding and the federal court grants it. TI appeals TI’s argument is that the preliminary injunction violates the AIA because it does not fit any of the exceptions. They’re right. SMC wants to make a timing argument, that they filed their case first and got the TRO. But just filing your case first doesn’t get you an advantage under the AIA but if you get the federal injunction before the state court starts its proceedings then the AIA doesn’t apply. What’s wrong with SMC’s timing argument? The TRO only was to forbid TI from licensing or something like that, it wasn’t to stop a state claim from happening. That injunction wasn’t requested until after the state court claim was filed. Let’s say that SMC files a case on Friday and makes a motion on Friday for

preliminary injunction to forbid TI from filing any case in state court against it, but the court does not rule. On Monday TI files a state case against SMC. The question is, does the fact that SMC has applied / made a motion for the injunction before the state court case began, take us out of the AIA territory? SPLIT IN THE CIRCUITS. ALL WRITS ACT Fed cout may issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their jurisdiction. Even though the AWA doesn’t include the AIA exceptions, federal courts will usually interpret it as having those exceptions. If the suit has not yet been filed in state court, the AWA may be used. The AIA on the other hand, may only come into effect after the state suit has been filed. In re Baldwin-United Corp. (2d Cir Ct App 1985): Huge class of plaintiffs with lots of claimsincluding state actions. Settlement was negotiated for 18 of 26 defendants. The class members will not be able to pursue their state actions as part of the MDL negotiation for