Comments

No comments yet. You can be the first!

Most popular documents in this category

Content extract

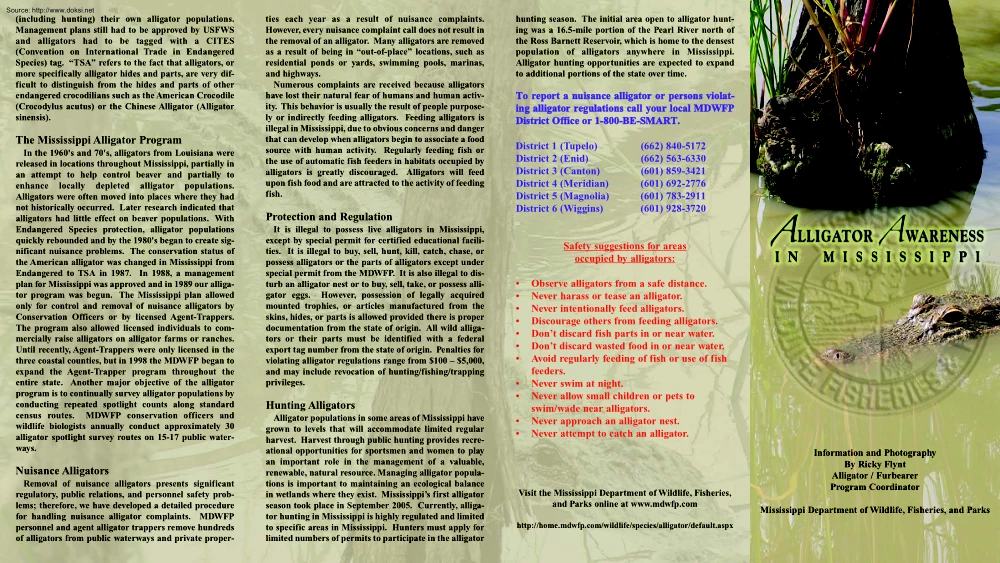

Source: http://www.doksinet (including hunting) their own alligator populations. Management plans still had to be approved by USFWS and alligators had to be tagged with a CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) tag. “TSA” refers to the fact that alligators, or more specifically alligator hides and parts, are very difficult to distinguish from the hides and parts of other endangered crocodilians such as the American Crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) or the Chinese Alligator (Alligator sinensis). The Mississippi Alligator Program In the 1960's and 70's, alligators from Louisiana were released in locations throughout Mississippi, partially in an attempt to help control beaver and partially to enhance locally depleted alligator populations. Alligators were often moved into places where they had not historically occurred. Later research indicated that alligators had little effect on beaver populations. With Endangered Species protection, alligator

populations quickly rebounded and by the 1980's began to create significant nuisance problems. The conservation status of the American alligator was changed in Mississippi from Endangered to TSA in 1987. In 1988, a management plan for Mississippi was approved and in 1989 our alligator program was begun. The Mississippi plan allowed only for control and removal of nuisance alligators by Conservation Officers or by licensed Agent-Trappers. The program also allowed licensed individuals to commercially raise alligators on alligator farms or ranches. Until recently, Agent-Trappers were only licensed in the three coastal counties, but in 1998 the MDWFP began to expand the Agent-Trapper program throughout the entire state. Another major objective of the alligator program is to continually survey alligator populations by conducting repeated spotlight counts along standard census routes. MDWFP conservation officers and wildlife biologists annually conduct approximately 30 alligator

spotlight survey routes on 15-17 public waterways. Nuisance Alligators Removal of nuisance alligators presents significant regulatory, public relations, and personnel safety problems; therefore, we have developed a detailed procedure for handling nuisance alligator complaints. MDWFP personnel and agent alligator trappers remove hundreds of alligators from public waterways and private proper- ties each year as a result of nuisance complaints. However, every nuisance complaint call does not result in the removal of an alligator. Many alligators are removed as a result of being in “out-of-place” locations, such as residential ponds or yards, swimming pools, marinas, and highways. Numerous complaints are received because alligators have lost their natural fear of humans and human activity. This behavior is usually the result of people purposely or indirectly feeding alligators Feeding alligators is illegal in Mississippi, due to obvious concerns and danger that can develop when

alligators begin to associate a food source with human activity. Regularly feeding fish or the use of automatic fish feeders in habitats occupied by alligators is greatly discouraged. Alligators will feed upon fish food and are attracted to the activity of feeding fish. Protection and Regulation It is illegal to possess live alligators in Mississippi, except by special permit for certified educational facilities. It is illegal to buy, sell, hunt, kill, catch, chase, or possess alligators or the parts of alligators except under special permit from the MDWFP. It is also illegal to disturb an alligator nest or to buy, sell, take, or possess alligator eggs However, possession of legally acquired mounted trophies, or articles manufactured from the skins, hides, or parts is allowed provided there is proper documentation from the state of origin. All wild alligators or their parts must be identified with a federal export tag number from the state of origin. Penalties for violating alligator

regulations range from $100 – $5,000, and may include revocation of hunting/fishing/trapping privileges. Hunting Alligators Alligator populations in some areas of Mississippi have grown to levels that will accommodate limited regular harvest. Harvest through public hunting provides recreational opportunities for sportsmen and women to play an important role in the management of a valuable, renewable, natural resource. Managing alligator populations is important to maintaining an ecological balance in wetlands where they exist. Mississippi’s first alligator season took place in September 2005. Currently, alligator hunting in Mississippi is highly regulated and limited to specific areas in Mississippi. Hunters must apply for limited numbers of permits to participate in the alligator hunting season. The initial area open to alligator hunting was a 165-mile portion of the Pearl River north of the Ross Barnett Reservoir, which is home to the densest population of alligators anywhere

in Mississippi. Alligator hunting opportunities are expected to expand to additional portions of the state over time. To report a nuisance alligator or persons violating alligator regulations call your local MDWFP District Office or 1-800-BE-SMART. District 1 (Tupelo) District 2 (Enid) District 3 (Canton) District 4 (Meridian) District 5 (Magnolia) District 6 (Wiggins) (662) 840-5172 (662) 563-6330 (601) 859-3421 (601) 692-2776 (601) 783-2911 (601) 928-3720 Safety suggestions for areas occupied by alligators: • • • • • • • • • • • Observe alligators from a safe distance. Never harass or tease an alligator. Never intentionally feed alligators. Discourage others from feeding alligators. Don’t discard fish parts in or near water. Don’t discard wasted food in or near water. Avoid regularly feeding of fish or use of fish feeders. Never swim at night. Never allow small children or pets to swim/wade near alligators. Never approach an alligator nest. Never attempt

to catch an alligator. Visit the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks online at www.mdwfpcom http://home.mdwfpcom/wildlife/species/alligator/defaultaspx Information and Photography By Ricky Flynt Alligator / Furbearer Program Coordinator Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks Source: http://www.doksinet Alligator Awareness Alligators may be found in most of Mississippi’s major rivers, creeks, oxbows, and reservoirs, as well as some small lakes, ponds, and sloughs. When alligators are encountered: avoid close contact, keep a safe distance, and warn others who may be in the vicinity and unaware. Large alligators are capable of attacking and causing serious injury or death to humans, pets, and livestock. Alligators can travel as fast as a horse for short distances across land and water. Alligators are stealthy predators and use the element of surprise. Their presence may not be easily detected. Therefore, always use caution in areas known to

occupy alligators. Distribution The American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) is found throughout the southeastern United States, up the Atlantic coastal plain to North Carolina and west to central Texas to southeastern Oklahoma. In Mississippi, alligators are most abundant in Jackson, Hancock, and Harrison counties, but have been recorded as far north as Coahoma and Tunica counties. The Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, & Parks (MDWFP) has conducted regular spotlight counts since the early 1970's. The alligator population in Mississippi has remained fairly stable in the coastal counties, but the population in the remainder of the state has increased dramatically. Alligators are now locally abundant in areas of suitable habitat throughout the southern two-thirds of the state, particularly in the Pearl River drainage in and around Ross Barnett Reservoir; most major river drainage systems (e.g, Big Black, Bayou Pierre, Steele Bayou, Big Sunflower, Little

Sunflower, and the Pascagoula River and associated tributaries) ; in oxbows and swamps of the Delta, where they pose a particular nuisance for catfish farmers; in and around the Noxubee, Panther Swamp, Hillside, and Yazoo National Wildlife Refuges; and in oxbows, lakes and barrow-pits along the entire Mississippi River. A survey of MDWFP field officers, biologists, and technicians in 2006 revealed the existence of alligators in 74 of 82 counties. Alligators were described as “frequently occurring” in 13 counties and “common” in 25 other counties. Biology Alligators are cold-blooded reptiles. They reach sexual maturity once they grow to about 6-7 feet long Alligator growth rates vary, but in adequate habitats young alligators may grow as much as 8-12 inches each year. However, growth rates of mature alligators (over 7 feet) may decrease significantly. Larger alligators (over 10 feet) have been documented to grow as little as one inch in a year. After reaching 3-4 feet in

length, an alligator has few predators, with the exception of humans and other alligators; therefore, most alligators that survive the first 3-5 years will likely become mature adults. Females usually begin building nests and laying eggs during early June to mid-July. Nests typically contain 2040 eggs Incubation lasts 60 days and young typically hatch during mid-August to mid-September. Only the female takes part in guarding the nest and rearing young. Young alligators stay in a pod within close vicinity of their mother and siblings for 2-3 years Alligator eggs and hatchlings are preyed upon by many predators including raccoons, coyotes, great blue herons, other wading birds, skunks, mink, and fish. Generally, only about 15-20% of eggs from a clutch will hatch and survive the first three years; in some areas, survival may be much lower due to nest predation, mainly by raccoons. Mature male alligators are cannibalistic, particularly during times of breeding and environmental stress The

MDWFP has documented a 10 foot 2 inch male alligator that swallowed a 5 foot 2 inch male alligator, whole. Alligators are not true “hibernators,” but do become mostly dormant from late fall to early spring. Alligators spend the winter in dens dug out along the edges of gator holes, bayous, riverbanks, ponds, oxbows, and even abandoned beaver burrows. Depending on the weather, they generally enter dens around mid-November and do not eat for the next four or five months. On warm, sunny days they may come out of dens to bask, but usually do not venture far from den sites. Alligators are cold-blooded and cannot digest prey in cold temperatures; they must maintain a body temperature around 73 degrees in order to digest food. In the coastal marshes, alligators wallow out shallow pools called “gator holes”. Many other marsh inhabitants depend on the gator holes as sources of fresh water and breeding pools for amphibians, crustaceans, and fish. Alligators will often travel long

distances from den sites after emerging in the spring to search for food and mates, and young alligators disperse in search of new territory. Breeding generally occurs in late April and May This time period (April-June) is when the MDWFP receives the most nuisance complaint calls. Juvenile males (4-7 feet long) may travel significant distances to disperse into territories not occupied by other adult males, who are very territorial during the breeding season. History of Regulations Alligators became rare throughout most of their range by the 1960's, mainly as a result of over-harvest and lack of protective regulations. In 1967, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) listed the American alligator as an Endangered Species under the newly enacted Endangered Species Convention Act. Once protected, however, alligators quickly rebounded and by the mid1970's the listing was modified for Louisiana, Florida, and later Georgia to Threatened by Similarity of Appearance (TSA). The TSA

designation meant that alligators were now known to be abundant in parts of their range and states were allowed to begin managing

populations quickly rebounded and by the 1980's began to create significant nuisance problems. The conservation status of the American alligator was changed in Mississippi from Endangered to TSA in 1987. In 1988, a management plan for Mississippi was approved and in 1989 our alligator program was begun. The Mississippi plan allowed only for control and removal of nuisance alligators by Conservation Officers or by licensed Agent-Trappers. The program also allowed licensed individuals to commercially raise alligators on alligator farms or ranches. Until recently, Agent-Trappers were only licensed in the three coastal counties, but in 1998 the MDWFP began to expand the Agent-Trapper program throughout the entire state. Another major objective of the alligator program is to continually survey alligator populations by conducting repeated spotlight counts along standard census routes. MDWFP conservation officers and wildlife biologists annually conduct approximately 30 alligator

spotlight survey routes on 15-17 public waterways. Nuisance Alligators Removal of nuisance alligators presents significant regulatory, public relations, and personnel safety problems; therefore, we have developed a detailed procedure for handling nuisance alligator complaints. MDWFP personnel and agent alligator trappers remove hundreds of alligators from public waterways and private proper- ties each year as a result of nuisance complaints. However, every nuisance complaint call does not result in the removal of an alligator. Many alligators are removed as a result of being in “out-of-place” locations, such as residential ponds or yards, swimming pools, marinas, and highways. Numerous complaints are received because alligators have lost their natural fear of humans and human activity. This behavior is usually the result of people purposely or indirectly feeding alligators Feeding alligators is illegal in Mississippi, due to obvious concerns and danger that can develop when

alligators begin to associate a food source with human activity. Regularly feeding fish or the use of automatic fish feeders in habitats occupied by alligators is greatly discouraged. Alligators will feed upon fish food and are attracted to the activity of feeding fish. Protection and Regulation It is illegal to possess live alligators in Mississippi, except by special permit for certified educational facilities. It is illegal to buy, sell, hunt, kill, catch, chase, or possess alligators or the parts of alligators except under special permit from the MDWFP. It is also illegal to disturb an alligator nest or to buy, sell, take, or possess alligator eggs However, possession of legally acquired mounted trophies, or articles manufactured from the skins, hides, or parts is allowed provided there is proper documentation from the state of origin. All wild alligators or their parts must be identified with a federal export tag number from the state of origin. Penalties for violating alligator

regulations range from $100 – $5,000, and may include revocation of hunting/fishing/trapping privileges. Hunting Alligators Alligator populations in some areas of Mississippi have grown to levels that will accommodate limited regular harvest. Harvest through public hunting provides recreational opportunities for sportsmen and women to play an important role in the management of a valuable, renewable, natural resource. Managing alligator populations is important to maintaining an ecological balance in wetlands where they exist. Mississippi’s first alligator season took place in September 2005. Currently, alligator hunting in Mississippi is highly regulated and limited to specific areas in Mississippi. Hunters must apply for limited numbers of permits to participate in the alligator hunting season. The initial area open to alligator hunting was a 165-mile portion of the Pearl River north of the Ross Barnett Reservoir, which is home to the densest population of alligators anywhere

in Mississippi. Alligator hunting opportunities are expected to expand to additional portions of the state over time. To report a nuisance alligator or persons violating alligator regulations call your local MDWFP District Office or 1-800-BE-SMART. District 1 (Tupelo) District 2 (Enid) District 3 (Canton) District 4 (Meridian) District 5 (Magnolia) District 6 (Wiggins) (662) 840-5172 (662) 563-6330 (601) 859-3421 (601) 692-2776 (601) 783-2911 (601) 928-3720 Safety suggestions for areas occupied by alligators: • • • • • • • • • • • Observe alligators from a safe distance. Never harass or tease an alligator. Never intentionally feed alligators. Discourage others from feeding alligators. Don’t discard fish parts in or near water. Don’t discard wasted food in or near water. Avoid regularly feeding of fish or use of fish feeders. Never swim at night. Never allow small children or pets to swim/wade near alligators. Never approach an alligator nest. Never attempt

to catch an alligator. Visit the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks online at www.mdwfpcom http://home.mdwfpcom/wildlife/species/alligator/defaultaspx Information and Photography By Ricky Flynt Alligator / Furbearer Program Coordinator Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks Source: http://www.doksinet Alligator Awareness Alligators may be found in most of Mississippi’s major rivers, creeks, oxbows, and reservoirs, as well as some small lakes, ponds, and sloughs. When alligators are encountered: avoid close contact, keep a safe distance, and warn others who may be in the vicinity and unaware. Large alligators are capable of attacking and causing serious injury or death to humans, pets, and livestock. Alligators can travel as fast as a horse for short distances across land and water. Alligators are stealthy predators and use the element of surprise. Their presence may not be easily detected. Therefore, always use caution in areas known to

occupy alligators. Distribution The American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) is found throughout the southeastern United States, up the Atlantic coastal plain to North Carolina and west to central Texas to southeastern Oklahoma. In Mississippi, alligators are most abundant in Jackson, Hancock, and Harrison counties, but have been recorded as far north as Coahoma and Tunica counties. The Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, & Parks (MDWFP) has conducted regular spotlight counts since the early 1970's. The alligator population in Mississippi has remained fairly stable in the coastal counties, but the population in the remainder of the state has increased dramatically. Alligators are now locally abundant in areas of suitable habitat throughout the southern two-thirds of the state, particularly in the Pearl River drainage in and around Ross Barnett Reservoir; most major river drainage systems (e.g, Big Black, Bayou Pierre, Steele Bayou, Big Sunflower, Little

Sunflower, and the Pascagoula River and associated tributaries) ; in oxbows and swamps of the Delta, where they pose a particular nuisance for catfish farmers; in and around the Noxubee, Panther Swamp, Hillside, and Yazoo National Wildlife Refuges; and in oxbows, lakes and barrow-pits along the entire Mississippi River. A survey of MDWFP field officers, biologists, and technicians in 2006 revealed the existence of alligators in 74 of 82 counties. Alligators were described as “frequently occurring” in 13 counties and “common” in 25 other counties. Biology Alligators are cold-blooded reptiles. They reach sexual maturity once they grow to about 6-7 feet long Alligator growth rates vary, but in adequate habitats young alligators may grow as much as 8-12 inches each year. However, growth rates of mature alligators (over 7 feet) may decrease significantly. Larger alligators (over 10 feet) have been documented to grow as little as one inch in a year. After reaching 3-4 feet in

length, an alligator has few predators, with the exception of humans and other alligators; therefore, most alligators that survive the first 3-5 years will likely become mature adults. Females usually begin building nests and laying eggs during early June to mid-July. Nests typically contain 2040 eggs Incubation lasts 60 days and young typically hatch during mid-August to mid-September. Only the female takes part in guarding the nest and rearing young. Young alligators stay in a pod within close vicinity of their mother and siblings for 2-3 years Alligator eggs and hatchlings are preyed upon by many predators including raccoons, coyotes, great blue herons, other wading birds, skunks, mink, and fish. Generally, only about 15-20% of eggs from a clutch will hatch and survive the first three years; in some areas, survival may be much lower due to nest predation, mainly by raccoons. Mature male alligators are cannibalistic, particularly during times of breeding and environmental stress The

MDWFP has documented a 10 foot 2 inch male alligator that swallowed a 5 foot 2 inch male alligator, whole. Alligators are not true “hibernators,” but do become mostly dormant from late fall to early spring. Alligators spend the winter in dens dug out along the edges of gator holes, bayous, riverbanks, ponds, oxbows, and even abandoned beaver burrows. Depending on the weather, they generally enter dens around mid-November and do not eat for the next four or five months. On warm, sunny days they may come out of dens to bask, but usually do not venture far from den sites. Alligators are cold-blooded and cannot digest prey in cold temperatures; they must maintain a body temperature around 73 degrees in order to digest food. In the coastal marshes, alligators wallow out shallow pools called “gator holes”. Many other marsh inhabitants depend on the gator holes as sources of fresh water and breeding pools for amphibians, crustaceans, and fish. Alligators will often travel long

distances from den sites after emerging in the spring to search for food and mates, and young alligators disperse in search of new territory. Breeding generally occurs in late April and May This time period (April-June) is when the MDWFP receives the most nuisance complaint calls. Juvenile males (4-7 feet long) may travel significant distances to disperse into territories not occupied by other adult males, who are very territorial during the breeding season. History of Regulations Alligators became rare throughout most of their range by the 1960's, mainly as a result of over-harvest and lack of protective regulations. In 1967, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) listed the American alligator as an Endangered Species under the newly enacted Endangered Species Convention Act. Once protected, however, alligators quickly rebounded and by the mid1970's the listing was modified for Louisiana, Florida, and later Georgia to Threatened by Similarity of Appearance (TSA). The TSA

designation meant that alligators were now known to be abundant in parts of their range and states were allowed to begin managing

Just like you draw up a plan when you’re going to war, building a house, or even going on vacation, you need to draw up a plan for your business. This tutorial will help you to clearly see where you are and make it possible to understand where you’re going.

Just like you draw up a plan when you’re going to war, building a house, or even going on vacation, you need to draw up a plan for your business. This tutorial will help you to clearly see where you are and make it possible to understand where you’re going.