Please log in to read this in our online viewer!

Please log in to read this in our online viewer!

No comments yet. You can be the first!

What did others read after this?

Content extract

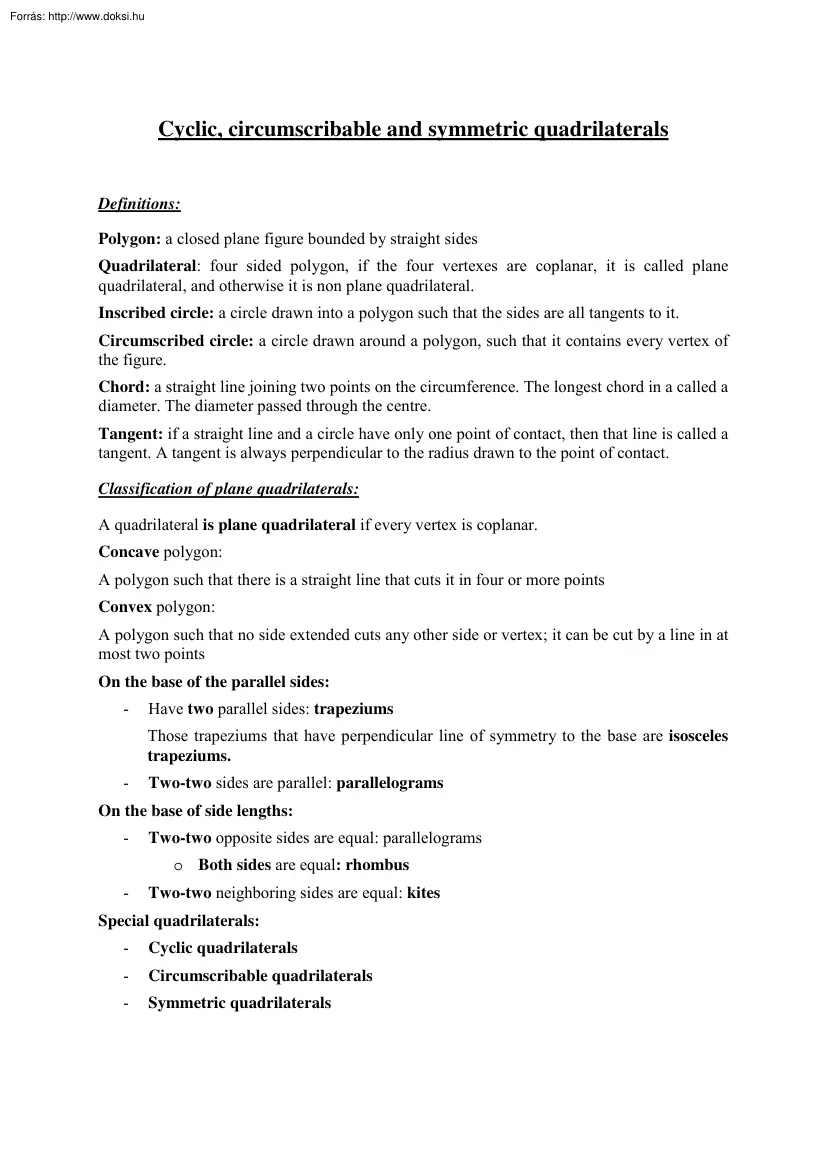

Cyclic, circumscribable and symmetric quadrilaterals Definitions: Polygon: a closed plane figure bounded by straight sides Quadrilateral: four sided polygon, if the four vertexes are coplanar, it is called plane quadrilateral, and otherwise it is non plane quadrilateral. Inscribed circle: a circle drawn into a polygon such that the sides are all tangents to it. Circumscribed circle: a circle drawn around a polygon, such that it contains every vertex of the figure. Chord: a straight line joining two points on the circumference. The longest chord in a called a diameter. The diameter passed through the centre Tangent: if a straight line and a circle have only one point of contact, then that line is called a tangent. A tangent is always perpendicular to the radius drawn to the point of contact Classification of plane quadrilaterals: A quadrilateral is plane quadrilateral if every vertex is coplanar. Concave polygon: A polygon such that there is a straight line that cuts it in four or more

points Convex polygon: A polygon such that no side extended cuts any other side or vertex; it can be cut by a line in at most two points On the base of the parallel sides: - Have two parallel sides: trapeziums Those trapeziums that have perpendicular line of symmetry to the base are isosceles trapeziums. - Two-two sides are parallel: parallelograms On the base of side lengths: - Two-two opposite sides are equal: parallelograms o Both sides are equal: rhombus - Two-two neighboring sides are equal: kites Special quadrilaterals: - Cyclic quadrilaterals - Circumscribable quadrilaterals - Symmetric quadrilaterals 1. Cyclic quadrilaterals Definition: A quadrilateral is cyclic if it can be inscribed in a circle, that is, if its four vertices belong to a single, circumscribed, circle. Theorem: A quadrilateral is cycle if and only if the sum of any of the two opposite angles is 180°. Proof: I. In every cyclic quadrilateral the sum of any of the two opposite angles is 180°.

AOC angle =2β (Since it is the central angle of the circumferential angle of ABC) COA angle=2δ (Since it is the central angle of the circumferential angle of ADC) O-point: 2β+2δ=360o ⇓ β+δ=180o Q.ed II. If the sum any of the two opposite angles is 180° in a quadrilateral, than it is cyclic. C” D 180°- 180°-α theorem above C 180°- C’ A α C δ 180°-α theorem above B First case: Let’s assume that C’ is inside the circumscribed circle of ABD triangle. Now DC’B angle is 180°- α since DAB angle is α. The line DC’ intersects the circle in point C We know from the proven theorem above, that ABCD is now cyclic, so C’CB angle is 180°- α. In the triangle BCC’, DC’B angle is an exterior angle, and we know it is the sum of the two interior angle not neighboring it. From this aspect, C’BC angle should be zero, that can only be, if C’≡C. Second case: Similarly to the first case, but now assume that C” is out of the circle. C”B

intersects the circle in point C. DCB angle is 180°- α, which is an exterior angle of triangle DCC”, so again C”DC angle should be zero. That can only be if C”≡C Q.ed 2. Circumscribable quadrilaterals Definition: A quadrilateral is circumscribable if it has an inscribed circle (that is, a circle tangent to all four sides). Theorem: A quadrilateral is circumscribable if and only if the sums of the length of its pair opposite sides are equal. Proof: I. In every circumscribable quadrilateral the sums of the length of its pair opposite sides are equal. Using the theorem, that the lengths of the tangents drawn from the same point are equal, we can set up a pair of equations: AB AD + DC = x + y + k + z + BC = x + k + y + z We know that addition is commutative, so AB + DC = AD + BC Q.ed II. If in a convex quadrilateral, the sums of the length of its pair opposite sides are equal, than it is circumscribable. From the given condition, a + c = b + d. Let a be the longest

side, from that b and d are convergent. If there were two equal sides ( a and c ), from the condition and from that a is the longest, they cannot be in front of each other. Side a and the extended line of b and d define a circle k. Let’s make an assumption that c does not touch k Now we have two cases: First is when c intersects k Second: c and k has no point of intersection c c’ c’ c b’ b k d’ d b’ b d d’ k a a Move line c parallel to herself until touches k. The quadrilateral that we get now is circumscribable, so a + c’ = b’ + d’. In the first case, c’ < c and b’ > b, d’ > d. From that, a + c > a + c’ = b’ + d’ > b + d which contradicts to the given a + c = b + d condition. With the same method, we get to a contradiction from case two as well. Now c’ > c, b’ < b and d’ < d. Then a + c < a + c’ = b’ + d’ < b + d, which also contradicts to the given a + c = b + d condition. Q.ed 3. Symmetric

quadrilaterals Linear symmetry - Isosceles trapezium • The two sloping sides are the same length • There is one line of symmetry • Its non-parallel sides are equal • Two pairs of adjacent angles are equal. - Kite • One pair of opposite angles equal and two pairs of adjacent sides equal. • One line of symmetry. It has no rotational symmetry Rotational symmetry - Parallelogram • Opposite sides are equal and parallel, • Opposite angles are equal. • A parallelogram has no lines of symmetry but it does have rotational symmetry. Linear and Rotational symmetry - Rhombus The opposite angles are equal The opposite sides are parallel All four sides are the same length. Two lines of symmetry (the diagonals), and a rotational symmetry around the intersection point of diagonals - Square • • • • • all four sides are equal • all four angles are right angles. • four lines of symmetry and rotational symmetry - Rectangle • • • the opposite sides are equal all four

angles are right angles two lines of symmetry and rotational symmetry 4. Applications - Regular polygons Area and volume calculation Maximum area problems Architecture, regular shapes, Center of mass in physics

points Convex polygon: A polygon such that no side extended cuts any other side or vertex; it can be cut by a line in at most two points On the base of the parallel sides: - Have two parallel sides: trapeziums Those trapeziums that have perpendicular line of symmetry to the base are isosceles trapeziums. - Two-two sides are parallel: parallelograms On the base of side lengths: - Two-two opposite sides are equal: parallelograms o Both sides are equal: rhombus - Two-two neighboring sides are equal: kites Special quadrilaterals: - Cyclic quadrilaterals - Circumscribable quadrilaterals - Symmetric quadrilaterals 1. Cyclic quadrilaterals Definition: A quadrilateral is cyclic if it can be inscribed in a circle, that is, if its four vertices belong to a single, circumscribed, circle. Theorem: A quadrilateral is cycle if and only if the sum of any of the two opposite angles is 180°. Proof: I. In every cyclic quadrilateral the sum of any of the two opposite angles is 180°.

AOC angle =2β (Since it is the central angle of the circumferential angle of ABC) COA angle=2δ (Since it is the central angle of the circumferential angle of ADC) O-point: 2β+2δ=360o ⇓ β+δ=180o Q.ed II. If the sum any of the two opposite angles is 180° in a quadrilateral, than it is cyclic. C” D 180°- 180°-α theorem above C 180°- C’ A α C δ 180°-α theorem above B First case: Let’s assume that C’ is inside the circumscribed circle of ABD triangle. Now DC’B angle is 180°- α since DAB angle is α. The line DC’ intersects the circle in point C We know from the proven theorem above, that ABCD is now cyclic, so C’CB angle is 180°- α. In the triangle BCC’, DC’B angle is an exterior angle, and we know it is the sum of the two interior angle not neighboring it. From this aspect, C’BC angle should be zero, that can only be, if C’≡C. Second case: Similarly to the first case, but now assume that C” is out of the circle. C”B

intersects the circle in point C. DCB angle is 180°- α, which is an exterior angle of triangle DCC”, so again C”DC angle should be zero. That can only be if C”≡C Q.ed 2. Circumscribable quadrilaterals Definition: A quadrilateral is circumscribable if it has an inscribed circle (that is, a circle tangent to all four sides). Theorem: A quadrilateral is circumscribable if and only if the sums of the length of its pair opposite sides are equal. Proof: I. In every circumscribable quadrilateral the sums of the length of its pair opposite sides are equal. Using the theorem, that the lengths of the tangents drawn from the same point are equal, we can set up a pair of equations: AB AD + DC = x + y + k + z + BC = x + k + y + z We know that addition is commutative, so AB + DC = AD + BC Q.ed II. If in a convex quadrilateral, the sums of the length of its pair opposite sides are equal, than it is circumscribable. From the given condition, a + c = b + d. Let a be the longest

side, from that b and d are convergent. If there were two equal sides ( a and c ), from the condition and from that a is the longest, they cannot be in front of each other. Side a and the extended line of b and d define a circle k. Let’s make an assumption that c does not touch k Now we have two cases: First is when c intersects k Second: c and k has no point of intersection c c’ c’ c b’ b k d’ d b’ b d d’ k a a Move line c parallel to herself until touches k. The quadrilateral that we get now is circumscribable, so a + c’ = b’ + d’. In the first case, c’ < c and b’ > b, d’ > d. From that, a + c > a + c’ = b’ + d’ > b + d which contradicts to the given a + c = b + d condition. With the same method, we get to a contradiction from case two as well. Now c’ > c, b’ < b and d’ < d. Then a + c < a + c’ = b’ + d’ < b + d, which also contradicts to the given a + c = b + d condition. Q.ed 3. Symmetric

quadrilaterals Linear symmetry - Isosceles trapezium • The two sloping sides are the same length • There is one line of symmetry • Its non-parallel sides are equal • Two pairs of adjacent angles are equal. - Kite • One pair of opposite angles equal and two pairs of adjacent sides equal. • One line of symmetry. It has no rotational symmetry Rotational symmetry - Parallelogram • Opposite sides are equal and parallel, • Opposite angles are equal. • A parallelogram has no lines of symmetry but it does have rotational symmetry. Linear and Rotational symmetry - Rhombus The opposite angles are equal The opposite sides are parallel All four sides are the same length. Two lines of symmetry (the diagonals), and a rotational symmetry around the intersection point of diagonals - Square • • • • • all four sides are equal • all four angles are right angles. • four lines of symmetry and rotational symmetry - Rectangle • • • the opposite sides are equal all four

angles are right angles two lines of symmetry and rotational symmetry 4. Applications - Regular polygons Area and volume calculation Maximum area problems Architecture, regular shapes, Center of mass in physics

Just like you draw up a plan when you’re going to war, building a house, or even going on vacation, you need to draw up a plan for your business. This tutorial will help you to clearly see where you are and make it possible to understand where you’re going.

Just like you draw up a plan when you’re going to war, building a house, or even going on vacation, you need to draw up a plan for your business. This tutorial will help you to clearly see where you are and make it possible to understand where you’re going.